The Beatles' White Album: Five myths the 50th anniversary deluxe edition puts to the test

Did studio squabbles almost break up The Beatles? There are many myths surrounding the iconic group's ninth studio album. Kenneth Womack and Jason Kruppa dissect the rumours on its 50th anniversary

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the five decades since The Beatles released their ninth studio LP, popularly known as The White Album, the rock world has been rife with working assumptions about the double-record’s production. Indeed, the resulting mythologies are so profuse that they have become inseparable from our understanding of these recordings.

Apple’s release of a 50th-anniversary box set, including three discs of mostly unheard session outtakes and an accompanying book full of new details, begs for a reexamination of our beliefs about the making of The Beatles’ masterwork. Here are five points worth a re-think.

1. The sessions were unbearably tense

The history of The Beatles’ recordings during the production of The White Album, which spanned across five months from May through October 1968, is well-known – and rightly so – for the interpersonal tensions that plagued their professional lives during that period. With the demise of his five-year marriage to his estranged wife Cynthia, John Lennon had brought Yoko Ono into The Beatles’ workaday world, with the Japanese performance artist rarely leaving his side.

Meanwhile, the studio had seemingly become roiled by the bandmates’ anxieties, reaching a fever pitch as Paul McCartney insisted that the group remake his ska trifle “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” over and over again. As the bandmates’ patience grew unbearably thin, even producer George Martin fell afoul of their growing frustrations. When the producer commented on the quality of McCartney’s vocal, the “Cute Beatle” vented his rage at the usually staid music man up in the booth: “If you think you can do it better”, he bellowed at Martin, “why don’t you f***ing come down here and sing it yourself?”

While The Beatles’ tensions were undoubtedly real, the outtakes from The White Album box set – compiled by Giles Martin, the youngest son of the legendary producer – offer an intriguing counter-narrative to our understanding of the sessions’ history. From one take to the next, the bandmates appear to delight in each other’s company, reveling in the sheer joy of making music together.

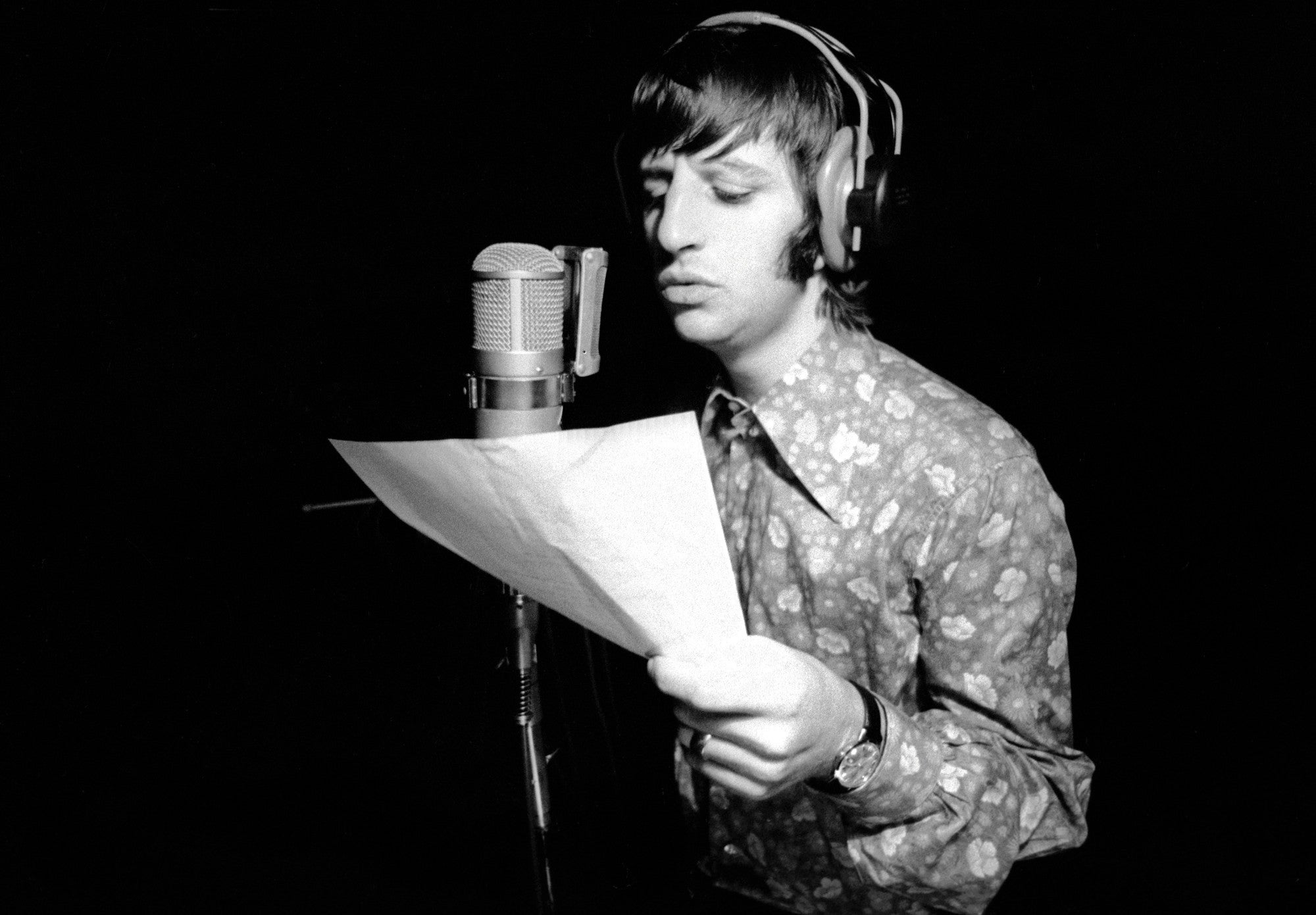

Take the country-and-western infused “Rocky Raccoon”, which begins with Lennon and McCartney’s playful banter about the doomed cowboy. And then there’s a quiet outtake of “Julia” in which a notably vulnerable Lennon solicits Martin’s advice about his performance of the tender ballad. The box set’s bonus recordings reach a moment of genuine tenderness during an acoustic version of “Good Night”, with Lennon, McCartney, and George Harrison affecting a gentle harmony in support of Ringo Starr’s warmhearted lead vocal. Sure, there may have been plenty of infighting with the Fab Four across that long summer of 1968, but there was still plenty of love and goodwill to go around.

2. It’s the “anti-production” album

Martin felt so marginalised during The White Album sessions that he went on holiday for the month of September, leaving his 21-year-old production assistant Chris Thomas in his place in the control booth. Martin’s baroque-classical aesthetic, which helped define Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the soundtrack for the ensuing Summer of Love, is largely absent here, yet The White Album’s tracks are no less “produced” than those of the previous year. As with its forerunner, all but a handful of The White Album’s four-track recordings required reduction mixes – bounce-downs from one tape to another to make room for more overdubs, a technique driven to its breaking point by Martin and The Beatles during the Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Magical Mystery Tour recordings.

Once The Beatles switched to eight-track recording more than halfway through the making of The White Album, the need for reduction mixes vanished, yet their deployment of overdubs remained just as plentiful and just as ambitious. Nearly all of the bandmates’ production tricks are in evidence on the album, including their inventive use of Automatic Double-Tracking (ADT), Abbey Road engineer Ken Townsend’s innovative tape-delay effect, as well as the processing of instruments to alter their sounds, tape loops, and half-speed recording.

The box set’s outtakes reveal that even a recording as seemingly straightforward as “Back in the USSR” was subjected to varispeed, whereby the backing track was adjusted as much as a whole step (from the key of G to A) for at least one overdub. Rather than no production, The Beatles had retained Martin’s method of crafting a recording track by track, fully integrating it into a more rock-oriented sound in comparison with Sgt Pepper, psychedelia’s master-text.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

3. It should have been one record instead of two

Beatles fans have long wrestled with Martin’s belief that The White Album would have been better served as a single-disc release. As it happened, Martin was responsible for this idea taking root, observing during a 1971 interview that he felt there was too much material and that he was sad when they didn’t pursue the idea of a more cohesive work like Pepper.

In truth, The Beatles’ producer was wedded to the aesthetic he had been building with them since 1962 (of which Pepper was the apotheosis), so much so that he couldn’t understand their desire to go in a new direction. “I didn’t like The White Album very much,” Martin later remarked. “They’d turned up with 36 songs after their Indian trip and they were pretty insistent that every song was to be included. I wanted to make it a single album, and I stressed to the boys that whilst they could record whatever they liked, we should weed out the stuff that wasn’t up to scratch and make a really super single album.”

By the time that work ensued on The White Album, The Beatles had effectively taken over the studio, leaving Martin uncertain about his place inside the band’s calculus. Not surprisingly, he was losing sense of the group’s evolving artistic trajectory. As early as May 1968, before they had even begun recording, McCartney mentioned to the New Musical Express that the new album could be one disc, or as many as three, but as the box set makes clear, their intent to record all of the songs they had composed in India while continuing to write new ones suggests the end result could hardly have been contained within the space of a single disc.

That they worked diligently on each song even into the fifth month of recording indicates that they were throwing nothing away, that they were hellbent on capturing the full extent of their artistic aspirations – no matter where and in what form it took them. In short, a single-disc White Album was Martin’s dream, not The Beatles’. By this point, Sgt Pepper was a fading image in their rearview mirror. Only the unimpeded sprawl of their ostensibly disparate songs, it seemed, would allow The Beatles to embrace their ever-broadening sensibilities.

4. It’s the break-up album

In truth, this may be the most complicated myth to deconstruct.

On December 8, 1970, Lennon told Rolling Stone’s Jann Wenner, “We broke up then,” in reference to The White Album sessions. Once again, history seems to be on Lennon’s side. Ringo quit the band briefly, engineer Geoff Emerick excused himself partway through, and each Beatle attested at one point or another about how difficult the White Album recordings had been. Every employee of Abbey Road studios interviewed by Mark Lewisohn for his influential Recording Sessions book affirmed how tense the atmosphere was during these sessions. And yet, during the publicity run in advance of the LP’s 50th-anniversary release, Giles Martin asserted in multiple interviews that the evidence on the session tapes tells a different story. In listening through those tapes, he heard a band in “good spirit”, and, as noted above, there’s ample evidence strewn throughout the box set to support his claim.

Take the group’s undeniable vibe during the unruly, delightfully unhinged jam that drives “Revolution” take 18 past the 10-minute mark into pure joy. Even during Ringo’s brief absence, Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison worked earnestly to bring “Back in the USSR” and “Dear Prudence” to fruition. By September, having entered their fourth month of production, the good-natured Beatles regularly descended into delightful interplay. Take the improvisations around the outtake of “I Will”, where in recording the moving romantic ballad Lennon and McCartney lose themselves in the saving grace of their humour. And then there’s the high-octane energy apparent in the basic rhythm tracks for the single version of “Revolution”, a blazing outtake of Elvis Presley’s “(You’re So Square) Baby I Don’t Care” during the “Helter Skelter” session, and a madcap early stab at “Birthday”. In each case, we discover just how much of a band they still were during the production of The White Album.

But even still, we can’t so easily dismiss the testimony of those present that the mood of these sessions was less than serene. The lingering void that manager Brian Epstein’s untimely death had left, coupled with the management of their new company Apple (for which The Beatles were woefully unprepared) were real stresses always bubbling underneath the double album’s production.

Giles Martin’s revisionism makes sense from a marketing angle: after all, he and Apple have a reissue to sell. But his rose-coloured perspective of The White Album emanates from the session reels, which find the band at its most productive and creative. As the box set demonstrates, when the red light was on and the tape was rolling, The Beatles could work with a single-minded purpose and still tap into their unique alchemy.

It’s tempting to believe that the truth lies somewhere between these extremes, between palpable tension and magical four-way collaboration. With the release of The White Album box set, we might more accurately come to believe that The Beatles’ musical bond was so strong that they could exist within the maelstrom and still manage to produce compelling, even groundbreaking work – if only for the time being.

5. It’s the album where The Beatles essentially act as solo artists

In his 1970 Rolling Stone interview, Lennon described The White Album as “just me and a backing group, Paul and a backing group…” And indeed, by this point in their partnership, Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison took matters into their own hands with their compositions, often working on them individually, and knowing full well that they could complete the recording process with little, if any, outside help.

Yet there are still plenty of instances during The White Album sessions where we witness all four Beatles working together in the studio and fulfilling a shared creative vision. As the box set reveals, the bandmates were in top ensemble form during the multilayered recordings for such tracks as “Glass Onion”, “Helter Skelter”, “I’m So Tired”, and “Sexy Sadie”, among others. But there is no better example of the group’s artistic fervour in full flower than “Happiness Is a Warm Gun”, the Lennon composition that was infamously inspired by an article in American Rifleman. Working with the same communal drive that brought them to the aesthetic heights of Sgt Pepper, “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” presented The Beatles in a moment of sublime concentration as they launch a four-pronged assault on the senses.

Sure, by this point in their storied career, The Beatles’ individual personalities were now so strong that they manifested unmistakably in each recording. And as music history proves, John, Paul, George, and Ringo wouldn’t be able to hold sway as a working rock ‘n’ roll group much longer. But for the brief shining moments that comprised the hard-wrought production of The White Album, they were fully committed to helping each other bring their compositions, one and all, across the finish line.

Jason Kruppa is a music historian and the host of the Producing The Beatles podcast, which explores the creation of The Beatles’ music from the perspective of producer George Martin.

Kenneth Womack is the author of a two-volume biography of the life and work of Beatles producer George Martin. He is Dean of the Wayne D. McMurray School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Monmouth University.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments