Whiplash has put drummers in their rightful place as music's irreplaceable root

Drummers are finally beginning to shake their tag as 'clueless thumpers'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A joke drummers tell about each other: “How many drummers does it take to change a light-bulb?” “Ten. One to screw it in. The rest to say they would have done it better.”

Other jokes simply caricature drummers as clueless thumpers, one step down even from the penniless slobs of standard musician jokes. Damien Chazelle’s new film Whiplash catches the truth of that insiders’ joke: that in its highest ranks, drumming is intensely, even insanely competitive. “Wipe that blood offa my drums,” jazz conductor Terence Fletcher (played by JK Simmons) sneers, having driven three drumming candidates past exhaustion, panting and blood-smeared, to see who can live there. Chazelle’s quietly clever, nerve-jangling movie should for once have audiences cheering lengthy drum solos, and viewing their players not as Cro-Magnon butts for ridicule, but music’s irreplaceable root.

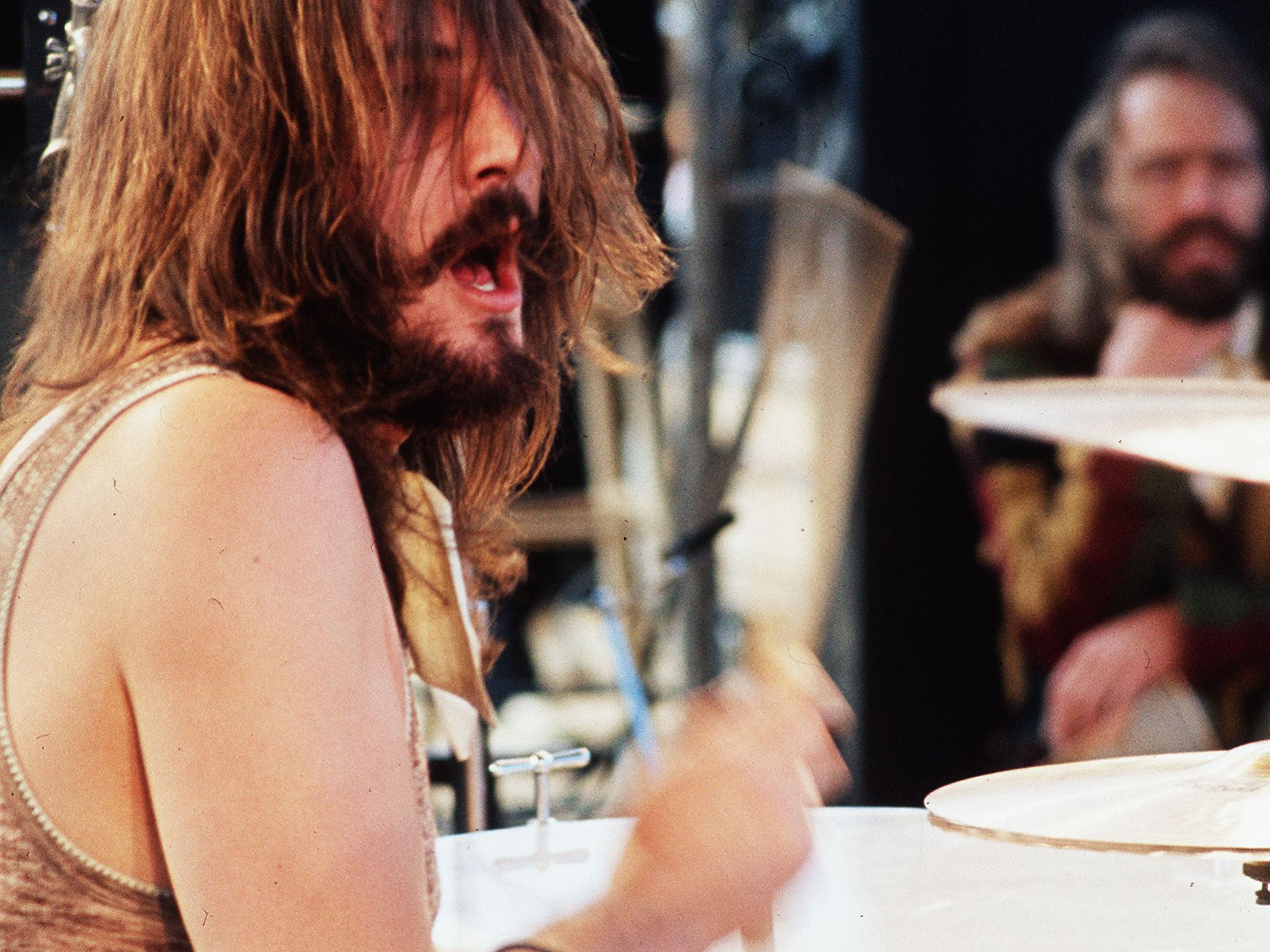

Cinema-goers also recently had stereotypes shattered by Beware of Mr. Baker (2013), a documentary in which ex-Cream drummer Ginger Baker exhibited malignant charisma, super-human endurance, contempt for almost all his rock rivals, and sentimental reverence for his jazz idols. “[Led Zeppelin’s] John Bonham once said there’s only two drummers in rock’n’roll, me and Ginger Baker,’” Baker told me when I met him, in a voice like tombstones tumbling. “My reaction to that was: ‘You little bastard!’ He was a good drummer, but nowhere near my standard. I like Ringo very much, he’s a hell of a good guy, but he ain’t a good drummer. He was okay for what they [The Beatles] were doing. But he was never called on to do anything difficult!”

Baker, Bonham and Who loon Keith Moon’s tireless hell-raising in the 1960s and 1970s constructed the cliché of rock-drummer behaviour behind The Muppet Show’s anarchic beat-master, Animal. Moon’s restlessness and capacity for sometimes absurd chaos and destruction was reflected in a style wholly suited to The Who’s musical needs. In his need to go too far, he hurled cars and TVs into swimming pools and, after rigging his drum-kit to explode, permanently damaged Pete Townshend’s hearing.

Baker and Bonham repeated their brutish stamina for pursuing drugs, booze and groupies in solo musical assaults. Cream’s “Toad” and Zeppelin’s “Moby Dick” were concert set-pieces which wallowed in the star drummer’s virtuosity. Bonham’s solo on the latter would sometimes pass the half-hour mark, sticks splintering in his bloody hands while his band-mates left him to it... He was 31 when a marathon booze binge finished him.

That showily flamboyant model is favoured in Whiplash, too. But most of British rock’s formative drummers, having begun playing before British rock existed, were, like Baker, steeped in jazz, and also offered that music’s subtly shifting swing. The Stones’ Charlie Watts has sat looking stonily bored at the back of their gigs for half a century, holding down an easy but breathing beat he could play in his sleep. The Kinks’ Mick Avory and, in the US, The Doors’ John Densmore, gave their bands a similar light, jazzy touch; Densmore was aiming for the seething polyrhythms created by John Coltrane’s drummer Elvin Jones when he backed Jim Morrison’s long poetic flights.

The Stranglers’ Jet Black even sneaked swing into punk, where drum solos were summarily outlawed, a diktat he was delighted by. “Pre-Beatles,” Black told me, “being the best virtuoso was the name of the game, and there were a million people better than me. You could play crap music, but extremely well. That wasn’t the life I wanted.”

Whiplash’s drummer hero Andrew (Miles Teller) certainly avoids the rock-animal clichés, piously dumping his girlfriend in his hunt to be a jazz great. The film does, though, propagate another unfortunate stereotype, the one indulged whenever a Cream crowd ritually yelled for Baker to play “Toad”. Andrew is drilled like an athlete or Marine by his tyrannical teacher. His quest is not only for perfect tempo, but brain-sizzling, crowd-dazzling speed more suited to an Apollo rocket-launch than music. The greatest drummers aren’t superb but hollow technicians of this sort, any more than they’re necessarily dim, or riotous, bloated alcoholics. It was James Brown who exclaimed, “Give the drummer some!” on 1967’s funk-creating single “Cold Sweat”, as Clyde Stubblefield launched under his instruction into an epochal solo. Tony Allen, a favourite drummer today of everyone from Damon Albarn to Brian Eno, was as important as his legendary Africa 70 band-leader Fela Kuti in the invention of Afro-beat. More recently, Fleet Foxes’ drummer Josh Tillman has outgrown his band to become multi-instrumentalist songwriter Father John Misty.

Nor is innovation the whole point. Art Blakey permanently changed jazz drumming in the 1940s, and put future great musicians from Horace Silver to Wynton Marsalis through the hard but fair school of his Jazz Messengers group for 40 years. When I saw him play in 1990, the year of his death aged 72, he was still tirelessly exploring every inch of his kit.

But unlike the almost demented, tunnel-visioned drumming displays in Whiplash, where Andrew is willing to be literally hit by a truck to get to the stand, stumbling on with a broken hand and staining his kit a sacrificial red, there is a warmth to Blakey’s beats. What matters is the sound of his drums rolling through a hundred albums on Blue Note and elsewhere, not dominating but motivating, driving his band’s music forward from deep inside with huge, human energy. Jazz “washes away the dust of everyday life,” Blakey famously said. If Whiplash gets more respect for drummers who do that, we’ll all benefit.

‘Whiplash’ is on general release

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments