Andrew Ridgeley on Wham!, ‘vile’ tabloids and George Michael: ‘He never saw himself growing old’

The Eighties pop star talks to Kate Mossman about his friendship with ‘Yog’ at school and in Wham!, why he was shocked but not surprised by his early death and the pact they made about the superstar singer not coming ‘out’

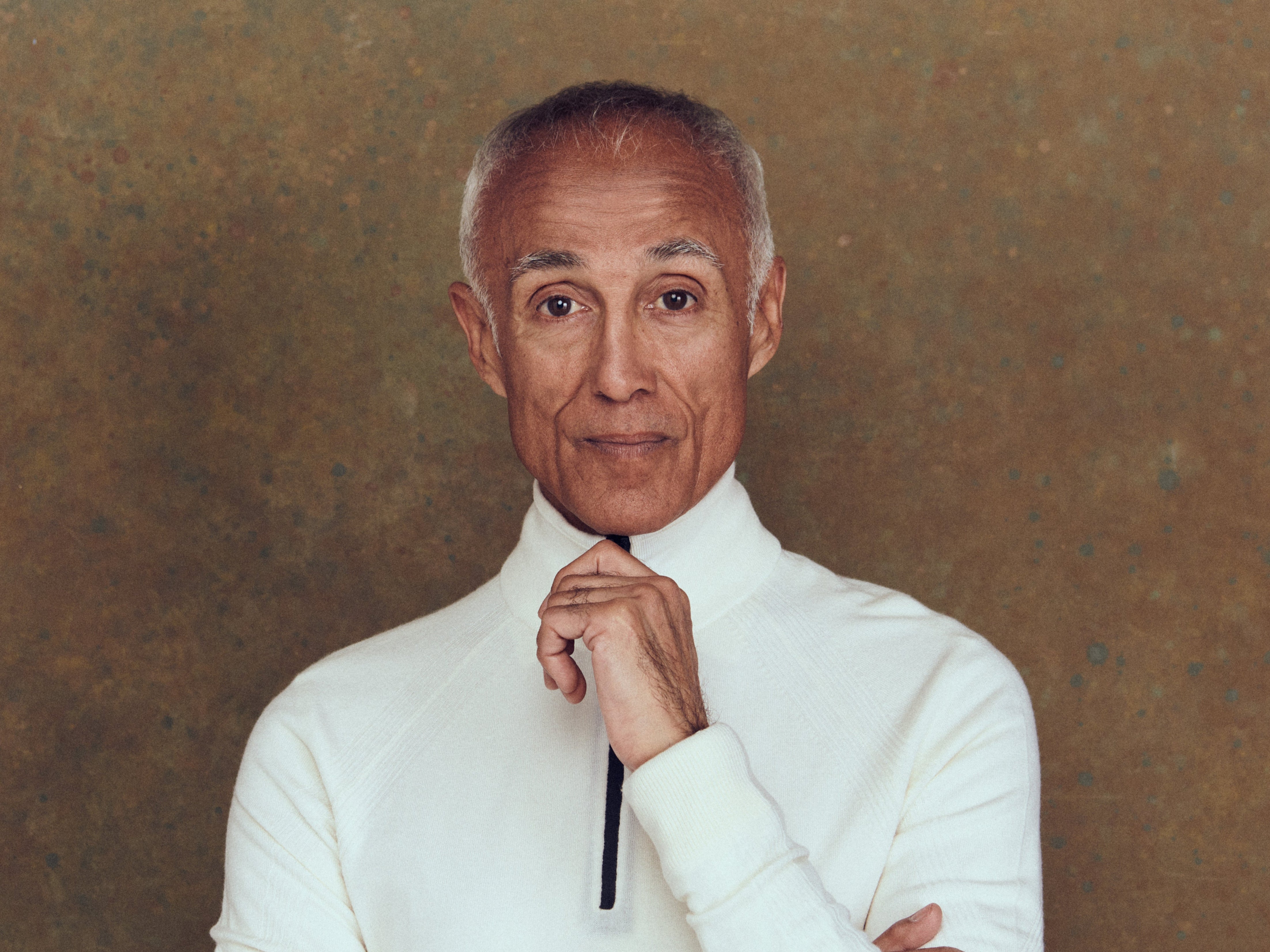

Andrew Ridgeley was, for many years, the big Eighties popstar who never spoke. Holed up in Cornwall with Keren Woodward from Bananarama (Wham! and Bananarama in the same converted barn in Wadebridge!), he occasionally campaigned for Surfers Against Sewage, but seemed unconcerned with the legacy of Wham!, spilling the beans on George Michael or recalling what it was like to have six number ones before ending his career abruptly after two sellout gigs at Wembley Stadium. When he pops up on his Zoom call today, he is still, at 60, a strange combination of enigmatic and completely unbothered. Straight in physical appearance, he has a neatly buzzed baldness and a black zip-up turtleneck: the sleek and slightly space-age appearance of a record producer or conceptual artist and a nice tan, as befits good living.

He chooses his words carefully, rolls them round his mouth with a hint of camp. He is sorry if his eyes keep flickering down to the edge of the screen: he is watching the Tour de France on an iPad at the same time as doing an interview. They’re climbing up the Col de la Columbière in the Alps right now, “a giant mountain of cycling lore”. Ridgeley recently completed a 1,000-mile event on his own bike, for charity, and is intrigued by physical challenges (he had a brief period as a racing driver in French Formula Three). At the same time, he has often said he is lazy.

He has had his own upheaval in the last few years: no longer with Woodward, he is single and spending more time in London. The man the press used to call Randy Andy recently dated the former model Amanda Cronin. He never likes to talk about his private life – not since The Sun fabricated a story about him having a fling with two Page Three girls at once and ran a photo of them both draped around his cardboard cutout. Fair enough, but why did he never speak about Wham!?

“There was nothing to say,” he says, reasonably. Now, there is, with Michael gone and the 40th anniversary of the band’s debut album. “It was an unspoken understanding between us that there would be no active development of the Wham! legacy, because Yog wouldn’t want anything overshadowing the GM career,” he says, using the nickname he gave his friend at the age of 12.

The relationship between the two members of Wham! is full of these “unspoken understandings”: Ridgeley agreed to drop co-writing credits (he still lives off royalties from “Wham! Rap”, “Club Tropicana” and “Careless Whisper”, which were written before the rule was imposed). He also agreed that the band’s career would end after their Wembley gigs so that George could go his own way. Yet, their old manager Simon Napier Bell says that Ridgeley was the “stronger” character in the group; as Michael himself wrote in his 1990 memoir Bare, “I created Wham in the image of a great friend.” Today Ridgeley says, “I think he saw in me some of that which he needed to assume, in order to explore his persona as a performer. I don’t know why!”

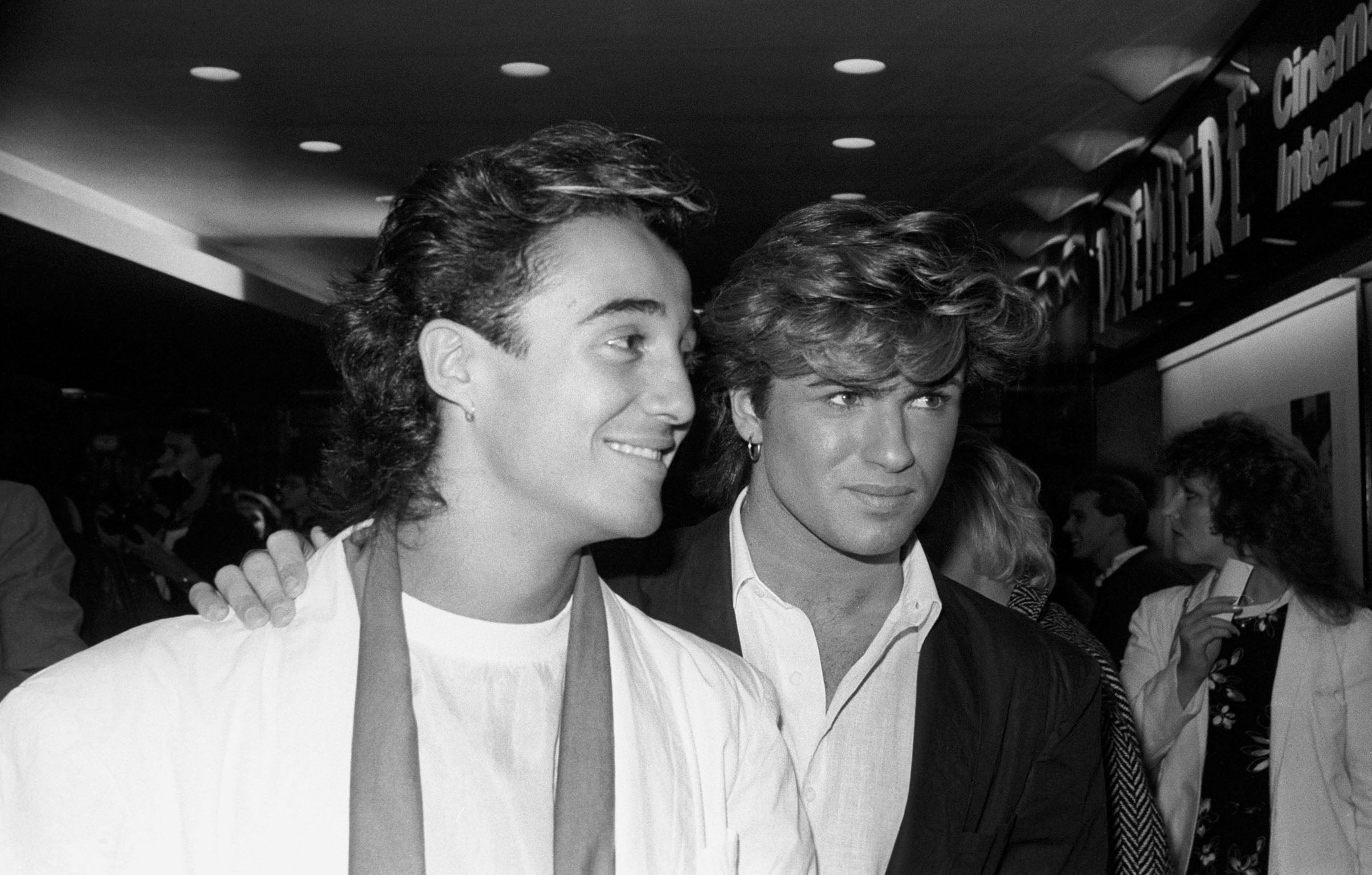

Ridgeley was bolder, more carefree and became Michael’s support network. Earlier this month, a new film by Chris Smith, Wham!, told one of pop’s strangest tales: how Michael modelled himself on his friend, overtook him creatively and no longer needed him. The funny thing is how utterly OK Ridgeley seemed to be with all of it.

What made him put his hand up in class and volunteer to look after the new boy, bespectacled, curly haired Georgios Panayiotou, at Bushey Meads comprehensive in the early Seventies? “Boredom,” he says. “It was something to do. I’d never had a new boy delivered unto my care. The decision was nothing to do with the way he looked, because you definitely wouldn’t have selected him on his appearance and that’s a fact.”

Ridgeley was cocky and confident: George’s family, he says, had done him no favours by giving him a fully Greek name in 1970s Hertfordshire. Ridgeley’s father, Alberto Zacharia, had come from Egypt, but you couldn’t tell: “Even though I’m dark-skinned like Dad was, I was incontrovertibly English as far as my schoolmates were concerned. But Yog wasn’t.” Ridgeley named him Yog because Georgios sounded like yoghurt. “He remained Yog forever more. George Michael was a persona: part of Yog, but it wasn’t the person, it was the artist.”

Michael would push his way through a transformative but painful solo career that reached for Michael Jackson levels of stardom. As he slid from the public eye in his forties, turning up occasionally in the tabloids to fall out of his car, or go into hospital with pneumonia, did Ridgeley, who remained a close friend, worry for his safety?

“Obviously his death came as a great shock. But he always said to me that he never saw himself growing old,” he says. “I couldn’t understand. For me, when I was a kid, all I wanted to be was an adult, and at this point in time, I still see a whole lot of life left to be lived. I couldn’t understand why Yog felt that way, but he was adamant that he could not see himself growing old.”

Michael told him this when they were very young? “Yes. I would say to him, ‘It’ll be nice in our old age, sitting on the veranda and chewing the fat and remembering this,” and he said, “I don’t think I’m going to reach old age.”

You get the feeling that Ridgeley has mulled over Michael’s psychology for years. “For George, being on stage was about validation of who he was, but for me it was just about playing live,” he says. While Ridgeley’s mother kept a scrapbook of the band’s early successes, George “did not conform to the idea of a son that his father [Jack, real name Kyriacos] had. There were several musicians in Jack’s family, so quite how he failed to recognise that his son had one of the best voices in music…”

Was Ridgeley really the “stronger character”? “Neither of us assumed a conscious superiority over the other,” he says. “Friendships don’t work like that, do they? We held a great affection for each other, we got a great deal of pleasure from each other’s company. He had an extremely juvenile sense of humour that fitted mine perfectly. Obviously, when his songwriting developed, the balance tilted towards Yog because he was more talented.”

He has not seen the two-part Channel 4 documentary Outed that followed the tabloids’ campaign to expose George Michael as gay in the 1990s. “The tabloids were vile. They always have been,” he says. They seem still to be on a campaign to out people, I suggest, given their recent interest in the sex lives of two TV presenters.

“Precisely, and they love that, and probably reserve their most poisonous response for those of their own, like Philip Schofield and Huw Edwards. It’s salacious and they love it. Obviously, George did feel it very keenly: he was very much torn between making an announcement and not doing so. It came at a cost. In the end, you know, what swung it was, certainly for us, was the potential reaction from his dad.”

In a single conversation, in a hotel room in Ibiza with their dancer Shirlie Holliman (then Ridgeley’s girlfriend), the three decided it would be better to keep Michael’s sexuality secret for the sake of his father. And it was never discussed again? “No, that was it.”

It’s moments like that which remind you how young they were. Perhaps it is futile to impose adult perspectives on people who get famous straight out of their teens: how many of us can see the future at 23? Ridgeley says Wham’s last ever gig was “a festival atmosphere. It wasn’t tinged with any kind of sorrow or sadness or sense of loss. We hoped for a record deal. You had a record deal, you wanted a hit single. Hit single, you want a number one. I had no trepidation about what my life would be from that point. Because to be in a band with Yog was the only ambition that I ever held with any great resolution; the prime feeling was just one of a job well done.”

To be in a band with George was the only ambition that I ever held with any great resolution

He had a solo album – Son of Albert – that received a half-star review from one particularly cruel publication and proved that there was no musical genius in this half of the band. “I personally had a fairly low opinion of record reviewers and the music press anyway,” he says. “If they really knew what they were doing, they’d be making the records rather than talking about them.”

I ask whether the stories about “Randy Andy” were put about by Wham’s people in order to take the heat off George, who was, Ridgeley says, “picking up whoever he liked in places that weren’t on the paparazzi radar”. He thinks not. He struggled with the realisation that his own private life was up for grabs and with the advice of older, wiser folk who told him there was little point in suing.

In their early days, Ridgeley and Michael loved wild formation dancing (a spin-off of Saturday Night Fever) and would often be found in the alternative nights of the suburbs, at Bogart’s nightclub in Harrow or the New Penny Disco in Watford. Later, in interviews, you saw them, arms draped over the back of each other’s chairs, fizzing with perpetual amusement at each other’s “juvenile” comments.

“That which made Wham! a little unique,” Ridgeley says, in his careful style, “and that which gave it the magic, was always an intangible thing. That is what’s in a friendship, especially that kind of fraternal bond which exceeds normal friendship. We were joined at the hip for a decade. The kind of friendship forged in the crucible of youth is really something special. You sit next to this person all day. There aren’t other circumstances, really, in life, apart from when you meet your partner, when you are so immersed in another person, and them in you.”

I ask if he has ever, since, had such a close friend in his life.

“No, I haven’t had friendships as close as I was to Yog,” he says. “But better at least to have had one, than none.”

The ‘Wham!’ documentary is out now on Netflix

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments