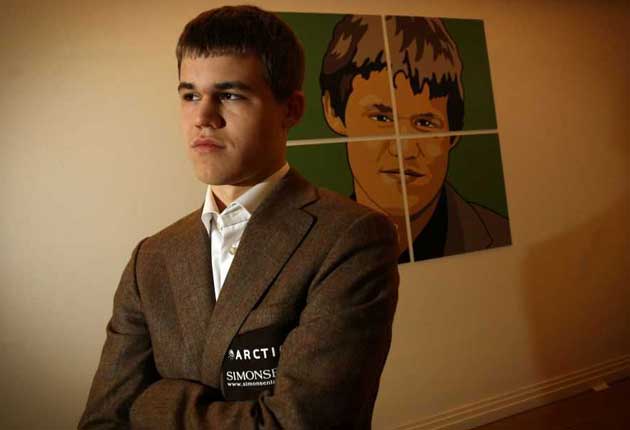

Magnus Carlsen: Move fast, play young

At just 19, Magnus Carlsen is the highest-ranking chess player in the world. As he arrives in the UK for a historic tournament, Simon Usborne meets him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The world's best chess player is hunched over a board in the bar of his London hotel. The pieces are lined up in neat rows, ready for battle, as Magnus Carlsen prepares to take on a man (me) whose grasp of the rules is the only thing between him and the imaginary title of the world's worst chess player. "Now I see the same as you," says Carlsen, 19. "We are equal."

Six moves and three minutes later, I ask Carlsen, who earlier revealed he can sometimes see 40 moves ahead, if victory is in sight. "No," he replies. "That would require quite a lot of cooperation from you." I make a rash move with my knight. "Now I have got the cooperation I wanted." Carlsen takes out the pawn protecting my king, sliding his queen next to it. "Checkmate."

It is the easiest and quickest win Carlsen will enjoy this week, but it won't be the first. Tomorrow, the Norwegian prodigy they call "the Mozart of chess" will do battle at the London Chess Classic at Olympia, Kensington. The biggest tournament to kick off in the capital for 25 years will see four British grandmasters take on some of the world's top players. But there is no doubt who has top billing.

In a game beset by images of bespectacled, pale-faced masterminds duelling in grey Eastern Bloc gymnasiums, Carlsen is seen as something of a saviour. Sure, he has the air of the nervous savant – a sense of simmering brilliance behind restless eyes – and he speaks shyly and laconically. But he is fresh-faced, has good hair and is handsome enough that, were his story to get the Hollywood treatment (and well it might) Matt Damon would be a shoo-in for the starring role.

"Carlsen is a vital part of raising the profile of chess," says Malcolm Pein, an accomplished player and director of the London Chess Classic. "Chess has always been very popular – in Britain 4 million people play regularly, which is more than play cricket, but what we lack is good role models for young people who play in clubs and schools."

It was only when his older sister, Ellen, got good at chess that Carlsen himself started to show an interest in the game. "I was always competitive growing up," he says. "And I really wanted to beat her – that was my first goal." Carlsen dispatched Ellen when he was eight and was soon peering over chess tables at national tournaments. He beat his dad, Henrick, aged 10 and, in 2004, stunned the chess world by defeating former world champion Anatoly Karpov and drawing a game against the king of the game, Garry Kasparov. He was 13. "Actually I wasn't very happy as I had a winning position," Carlsen says of the Kasparov clash. "But looking back, I'm not sure I appreciated what I had done."

It was a breakthrough year during which Carlsen entered the game's elite as one of its youngest grandmasters. His astonishing rise lead the Washington Post to make the Mozart comparison, one he now hears all the time. "I don't think it's very accurate," he says, bristling slightly. "Of course Mozart was a great genius so in a way it's nice, but it's wrong to think you can learn chess or music just like that. I worked very hard."

Kasparov was so impressed by Carlsen's dedication and extraordinary talent that, in 2005, after retiring as arguably the greatest player in the game's history, he invited Carlsen to Moscow, offering his services as a coach. For the second time in his short career, Carlsen raised eyebrows among chess watchers. "I said 'no'," he recalls. "I was developing in my own way and didn't feel I was ready for that kind of systematic coaching."

Kasparov, who has called Carlsen the "future of chess", made a second approach in January this year. This time, Carlsen agreed and many credit the partnership – Carlsen says they have concentrated on aggressive openings, Kasparov's trademark – with propelling the boy to the pinnacle of the game. "Everything Kasparov says is worth something in chess," Carlsen says. "It's great to work with him but also demanding. He expects a lot."

Carlsen's success has earned him celebrity status in Norway, where he lives with his family outside Oslo. He makes regular appearances on chat shows and is frequently mobbed by fans in a country not known as a power in the game. "In Norway, we are not good at many things, so when you win you become popular," he says. "And now chess has become popular, too, and people are changing their idea of the game." Pein hopes the Carlsen effect will come to bear on London this week as he seeks to win support for his bid to host the 2012 world championships.

In the meantime, Carlsen analyses the board after his eight-move rout. "Your previous move was rather weak because, additionally, I could have taken the knight or the queen," he says with deceptively gentle tone – Carlsen is a ruthless warrior on the board, who speaks of the "determination to destroy your opponent" necessary to be the best. He softens the blow by telling me he once beat a player in five moves. "We were nine," he adds, "but the other boy actually turned out to be a decent player." There's hope for me yet.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments