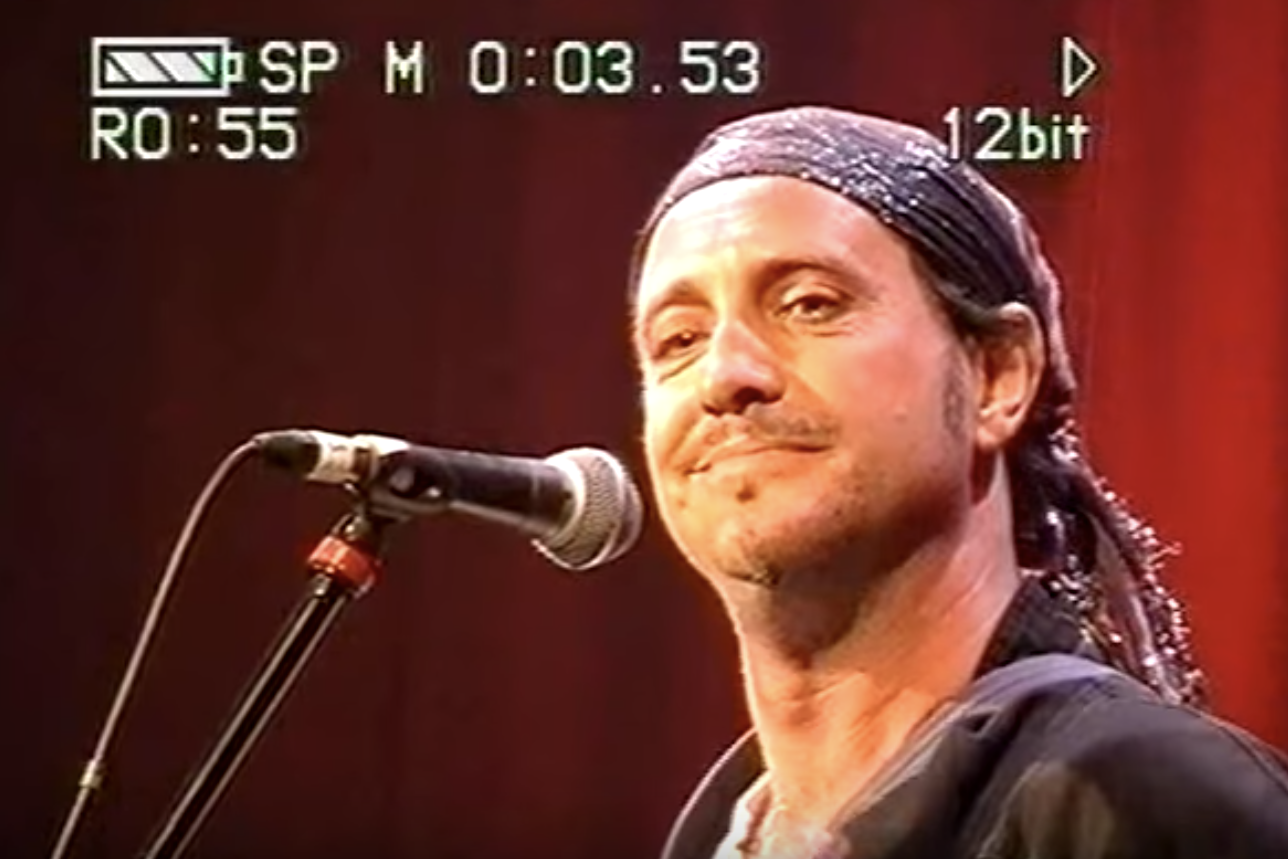

My dad, Ian Cognito, was a master of comic timing – even when he died on stage

The maverick standup achieved post-mortem fame last month after expiring in front of his audience. On the day his father is buried, Will Barbieri explores how his death framed a life well-lived

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After 30 years in the business Ian Cognito was in death, as he was in life, a hard act to follow.

He lived as a kind of showbusiness shaman, sitting and smoking by a fire on the banks of the river Avon under a bridge where he moored his boat, the Mermaid.

But while most people die with a whimper and some die with a bang, it is an ironic and beautiful sentiment to die, as Cognito did, with laughter.

On the night he died on stage at a club in Bicester, he was feeling dizzy, and the recording I found of a phone call we had a few hours earlier, illuminates, with hindsight, the slow fatigue of his voice and the fact I did most of the talking.

The promoter of the Lone Wolf comedy club, Andrew Bird, offered him an earlier slot, which anyone familar with “Cogs” knows he would never have taken. After all, there are standups and there are headliners: no one questioned which Cognito was.

As the comic prepared for his gig in the wings, morose yet agitated as he was on show nights, Bird suggested he take a shorter slot of twenty minutes, to which Cognito replied, “better do forty”, before swaggering out into the lights for the last time.

He smashed the gig.

Then, about twenty minutes in, my father, who I’d never seen sit down on stage except to play the guitar, and who was famous for pacing through audiences and shouting instead of using a microphone, sat down and exhaled.

A ruptured aortic dissection had killed him, swiftly and apparently without pain.

The audience laughed along, believing it was part of the act.

***

Everyone called my dad Cogs. Few people even knew his real name was Paul Barbieri until the BBC published it the next day.

A slow and incredulous wave of grief swept the comedy community in the wake of the news.

Industry heavyweights flooded the Twittersphere with tributes and memories of a man who was now unanimously revered.

While James Acaster remembered him pissing in a sink, and Danny Wallace remembered a terrifying phone call, Shappi Khorsandi recalled his blue eyes and what a joy he was to work with.

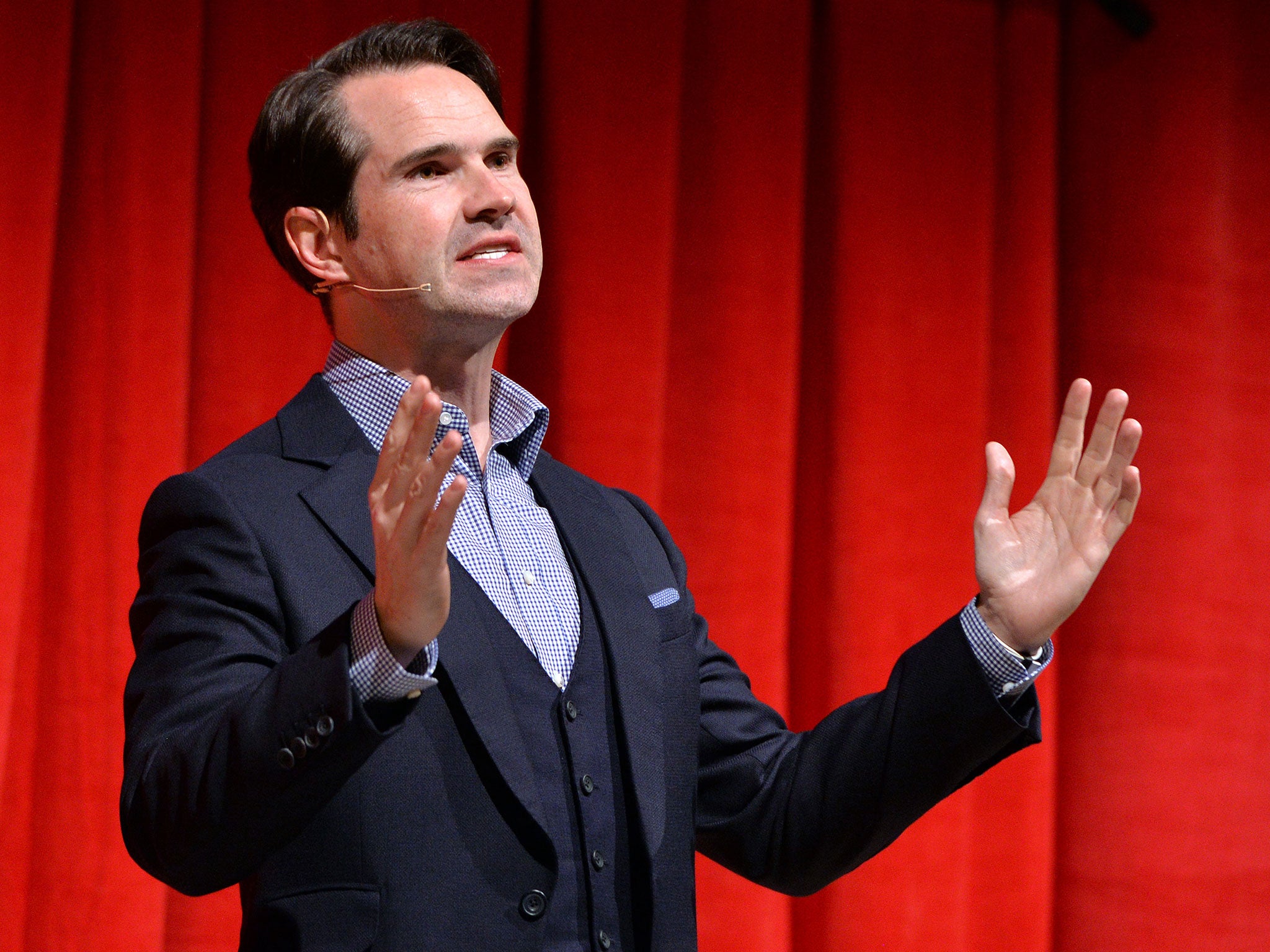

Jimmy Carr and Matt Lucas were among those who remembered his kindness when they started out.

This kindness and encouragement became a recurring theme throughout the tributes, in surprising contrast to one of his own on-stage confessionals: “You know how Spider-Man was bitten by a radioactive spider, and became like a spider? Well I must’ve been bitten by a radioactive c**t.”

Some comedians hammered nails into comedy club walls to hang their jackets on in deference to that favoured part of his routine, after which he would turn to the audience and announce: “Now you know two things about me… One: I don’t give a f**k. Two: I’ve got a hammer.”

Attic in Bicester, where he died, pinned up an engraved hammer and in Banbury they painted a mural for him.

In death, it seemed, he achieved the success he always needed but never wanted

The Strand pinned a picture of his face onto their backdrop, only to have a nail hammered through it by standup Jojo Sutherland later that night.

Articles about his death and tributes appeared in every major national paper from the Daily Star to The Telegraph. He was featured on the BBC and CNN and Fox News.

Cogs was mourned by comics and press from Australia and China to South America and the United States.

Reading his obituaries in The Times and The Guardian brought a wry smile to my face in an otherwise sad time: anecdotes were mistold and jokes misquoted but the sentiments steeled our family against the melancholy of mourning.

The affection evinced by the comedy community befitted the passing of a much loved icon.

In death, it seemed, he achieved the success he always needed but never wanted.

It is an unfortunate truism that some icons are more revered in death than life: Van Gogh, Tupac, Jesus

Cognito follows in this rich heritage, perhaps because the idea of an icon belies a liminal character, one who occupies or breaks the cultural thresholds their contemporaries cannot or will not traverse.

Because of this, like many iconoclastic people before him, Cogs lived hand to mouth, 50-pound note to 50-pound note and after years of hard living, offending club owners and fellow comics, and vehemently rejecting TV and corporate gigs, he became something of a pariah.

While contemporaries like Lee Mack, Bill Bailey, Jo Brand, Stewart Lee and Sean Lock became household names, Cognito felt obliged to lie in the bed he’d made himself.

Many promoters avoided him, as did clubs and much of the media; and when he died at 60 years old, he was, financially speaking, a very poor man.

But when, in some cruel twist of fate, he became famous post-mortem, the response was enormous.

In such cases, when only death offers such recognition, it begs the question, voiced in Cognito’s self-proclaimed cockney wide boy way: “Where were those c**ts last year?”

Indeed, where were the lights and laughter and outpouring of respect when Cognito journeyed on a thousand trains to a thousand pubs in a hundred towns at night?

Or when he showed up on time, every time, to almost every time smash the gig?

It was, in many ways a choice; a self-fulfilling prophecy in which he attacked all forms of authority and structure and took the consequences.

But the nature of artists apotheosised in death is always nuanced; does death give art greater legitimacy? Or does death cause people to reflect in sincere recognition of its worth? Or perhaps some characters are simply too problematic to achieve success in life.

It becomes hard to discern well-wishers from well-meaners, to differentiate those who truly knew the icon, who understood them and supported them in spite of social or professional backlash, from those who ride their mortal coattails for networking or self-promotion.

Of course, responses are nuanced too and they are, at once, beautiful and sad and never altogether insincere.

Because the death of a person, and subsequent construction of an icon, signifies a feeling of finality, of the extinction of an endangered breed that broke boundaries or predated a now commodified, commercialised or culturally integrated sphere.

This was Cogs.

Though he was undoubtedly a great, it is not his stand-up that venerates him, but how he shouldered the burden of a fading art, of alternative comedy.

Paul was kind and gentle and happiest with his boys, by a fire at high tide, surrounded by his plants and the spiders that visited him at night

With a defiant twinkle and raging integrity, he weathered the animosity of audiences and critics alike, facing down the corporate and television-based hegemony that encroached on the freedom of his artistic expression.

When Ian started out in the late 1980s, comedy was a bastion of free speech.

It represented the punk rock revolt against Thatcher’s Britain that music no longer offered. That’s how it stayed, for him.

So he would often open a show by doing exactly what he shouldn’t; whether verbally assaulting the audience, prolifically using words promoters had forbidden, like c**t, or cracking that slightly too topical gag that cut to the marrow: “Fair play to al-Qaeda for bombing London on 7/7, that way the yanks can’t f**k the date up this time”.

Or he would simply wear a dress and gob on the backdrop.

Any reaction was a good reaction; some cried, some screamed, some even laughed, but no one forgot.

And while he was loud, aggressive, painfully funny and had an uncompromising integrity that stifled his commercial success, his excessive lifestyle created a mythos around him.

A mythos that echoed through green rooms and backstages around the country and beyond when news of his death spread.

Because Cogs would always stay after gigs to talk and tell stories, especially if there was a drink in it.

That itself was a hangover from a bygone age, before acts dashed from gig to gig, soberly accumulating the means of their subsistence.

On the weekend Ian died, everyone stayed after the gig to talk and tell stories. Stories about Cogs.

Despite this, there is, of course, a man behind the myth and the moniker: my dad, Paul.

Paul was kind and gentle and happiest with his boys, by a fire at high tide, surrounded by his plants and the spiders that visited him at night.

He rented a small plot of land, on the river near Bristol, where we would spend long summer days eeking another year out of his narrow boat by simply applying another layer of sealant and John Dere green paint over the last, like age rings on a tree.

It was a 57-foot work in progress; it leaked; the engine was coaxed to life maybe once a decade; and he plugged its glassless windowpanes with polystyrene.

Yes, it was inaccessible and remote; but, like my father, also devoid of judgement and responsibilities and always welcoming to myself and the friends he saw there.

Though he often slept in his caravan, he spent his days on a sofa in his mole-riddled garden, where a homemade outhouse contained his camping toilet.

In his garden, the woodpile swelled and lobelia he had bought the week before he died was dotted haphazardly around

My brother Ollie and I recently moved in together, and Cogs, who often refused a bed in favour of sleeping on bare carpet, would have slept even more soundly if that carpet was his boys.

He never missed a chance to expound his happiness at the fact that my brother and I were friends in a way he and his brother never had been.

Ollie is a 27-year-old graphic designer who has never forgiven me for being born on his second birthday.

As kids we accompanied our dad to festivals and clubs and pubs from before I can remember, where we were nurtured by performers and managers and promoters, who took us under their wings in turn.

By the time I was legally allowed into these establishments I had probably been to more bars and clubs than almost any 18-year-old in the country.

He and my mother, Sarah Woollett, an actress and dancer turned teacher, had split in the late Nineties and thankfully she never knew the details of some of these adventures.

But she remained resolute in allowing him time with his kids and his unique method of fatherhood.

And this fatherhood was unconventional to say the least: some might have deemed it irresponsible or neglectful but we, and more importantly my mother, never did.

Dad preferred to trains us through life lessons and self-preservation rather than parental guidance or education.

He had hated his time at Catholic school and wanted us home schooled or educated by him. I’m glad my mum won that debate.

He once climbed onto Glastonbury’s Pyramid Stage to shout my name into the microphone and find me in the crowd.

His friends sometimes had to take on parenting duties or get us out of trouble if dad was otherwise indisposed.

Ollie and I were, in many ways, raised by the crazy, colourful, ridiculous, roving family that is the UK comedy and cabaret circuit.

Indeed, my life, apparently like so many others, would have been far less special without Ian Cognito in it.

So I find barbed solace in the fact that so much that defines me defined him too.

I didn’t get his scintillating eyes or his sense of humour; instead I got his temper, his crooked nose and perhaps, I like to think, a small fraction of that charisma and charm.

For the last year and a half Cogs was sober and healthier than ever.

He made progress with the Mermaid; shelves sprung up and flooring was laid down.

In his garden, the woodpile swelled and lobelia he had bought with Sarah the week before he died was dotted haphazardly around.

He died an iconic death but, by escaping his demons in life, circumvented its traditionally tragic narrative.

Even so, whether he likes it or not, Ian Cognito has become a comedy icon.

Those who flock to pay their respects today will read like the comedy industry’s new world order, and each will have a story about Cogs even if, as Omid Djalili said, it had to be told to the police.

So Cogs, Paul, Dad, best friend, liberator, pariah, and vanguard of free speech, enjoy the paradoxes of your sudden, if belated exultation.

Rest well and enjoy finding all the things you’ve lost in that warehouse in the sky.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments