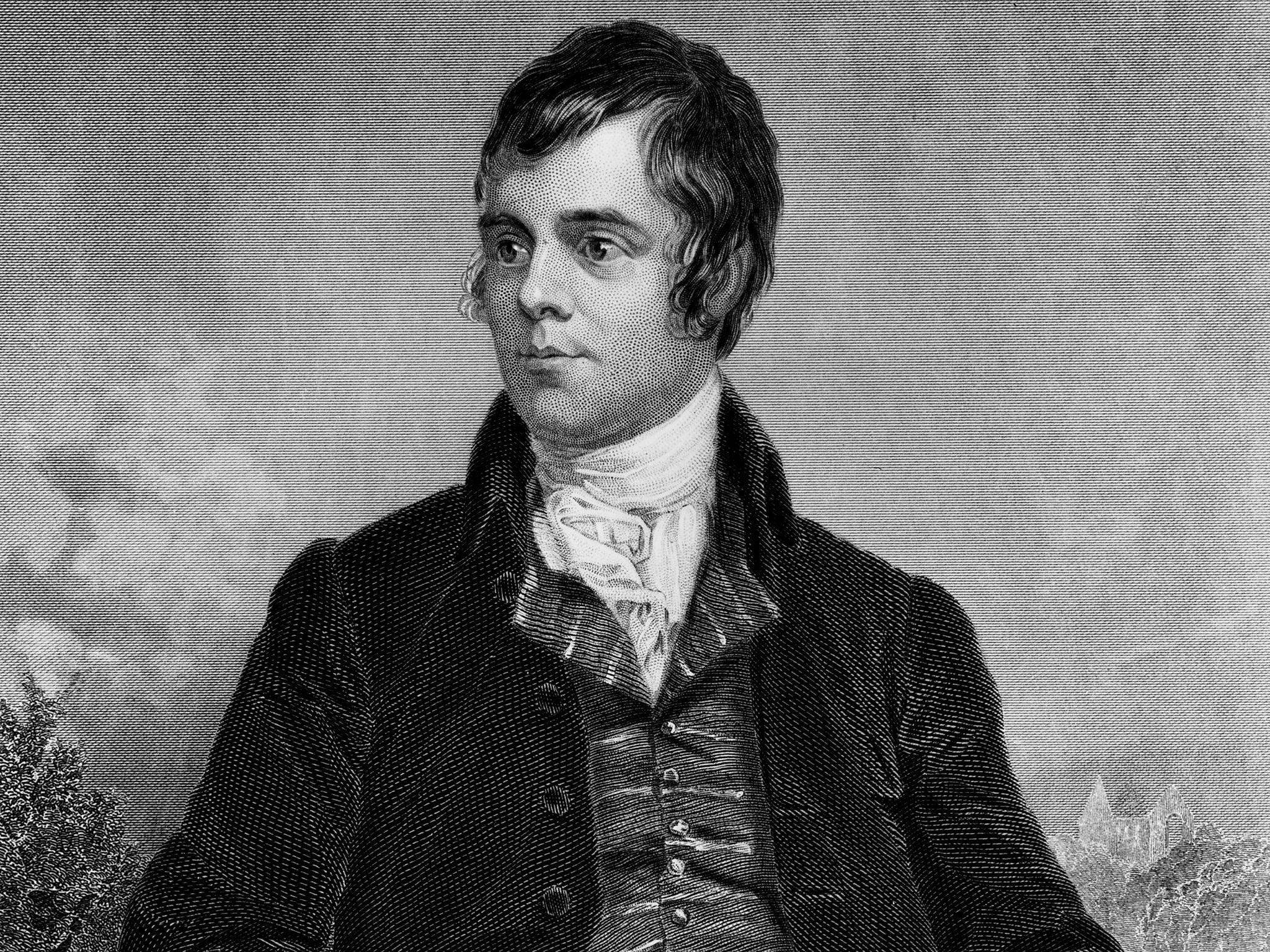

How nervy elites seized Robert Burns before radicals got there first

But the legacy of Scotland's national poet lives on

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two hundred years ago in 1817, Robert Burns’s bones were dug up, along with the coffin in which he had been laid to rest in 1796, in Dumfries in south-west Scotland. Workmen were preparing for the re-interment of Scotland’s national poet beneath a mausoleum being built as a more fitting memorial.

The workmen present stood in the cramped graveyard of St Michael’s Church, “their frames thrilling with some indefinable emotion, as they gazed on the ashes of him whose fame is as wide as the world itself”, to use the words of a report at the time.

Barely two decades after his death, Burns had already become a secular saint.

Yet his legacy was still very much up for grabs at the time – unlike today. Now that it is time once again to toast Burns’ immortal memory on 25th January, both in Scotland and around the world, how does our perception of him now compare to then?

And how did Burns make the journey from Edinburgh drawing rooms at the turn of the 18th century to his global superstardom today?

The battle for Burns

The Dumfries mausoleum was the first of numerous Burns memorials that studded the towns of lowland Scotland by the end of the Victorian era. Most were statues, erected in an informal race between Scotland’s urban elites. Overseas, above all in Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand, Scots settlers and their descendants soon followed suit.

The sentimental appeal of Burns’ writing and his preservation in verse of a rural Scotland fast disappearing was one of the reasons he was well-loved. But this alone can’t explain why from the time of his death onwards, his legacy has been fought over.

Much has to do with establishment fears about where the cult of Burns might lead. Terrified by the prospect of revolution and radical violence in Scotland inspired by songs such as “A Man’s a Man”, his first editors elided poems and sections of them that asserted human dignity regardless of rank, title or wealth.

As The Scotsman reminded its readers at the time, the “chief characteristic of Burns was his Nationality.... He was utterly and intensely, before and beyond everything, a Scotchman”.

There were those who believed Burns had rescued Scotland from oblivion – above all through his work as a collector, adaptor and writer of Scottish song.

If Scots felt alienated within a union in which England was politically and culturally dominant, Burns offered them a sense of pride and self-respect that fuelled the emerging Home Rule movement.

Scotland the what?

Burns’ legacy as a moving force in Scotland’s history has now dissolved. He has become a malleable symbol of the nation, functioning partly as a tourist attraction whose familiar face can sell shortbread, whisky, ales and tea towels. As usual, nationalists and unionists and other factions will claim him as one of their own – but mainly by judicious selection from his works and no little credibility stretching.

At the best of the Burns suppers, attendees will be reminded that Burns spoke for no one party. He spoke for humanity itself, warts and all. Right now, in the wake of Brexit and the inauguration of President Trump, that is precisely why he is still worth reading.

rofessor of Scottish history, University of Dundee. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments