The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Sid Meier: ‘I’m not sure I’d play Civilisation if it was released today’

The creator of one of the most complex and influential video games of all time talks to Ed Cumming about his new autobiography, developments in technology, and storytelling

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As Sid Meier fires up Zoom from his home in Maryland, it occurs to me that this mild-mannered video game designer has commanded more of my attention than any other artist.

Watching all the James Bond films would take 50 hours or so. To read all of Harry Potter, maybe 60. Meier’s work scoffs at such dilettantism. It’s almost unbearable to try to work out how much time I’ve given Railroad Tycoon, Pirates and the various versions of Civilisation, but I’m sure it would be more than 1,000 hours. When it comes to Meier, there aren’t many agnostics. Either the name will mean nothing to you or it will inspire memories of high-seas buccaneering, railway oligarchy, and world domination.

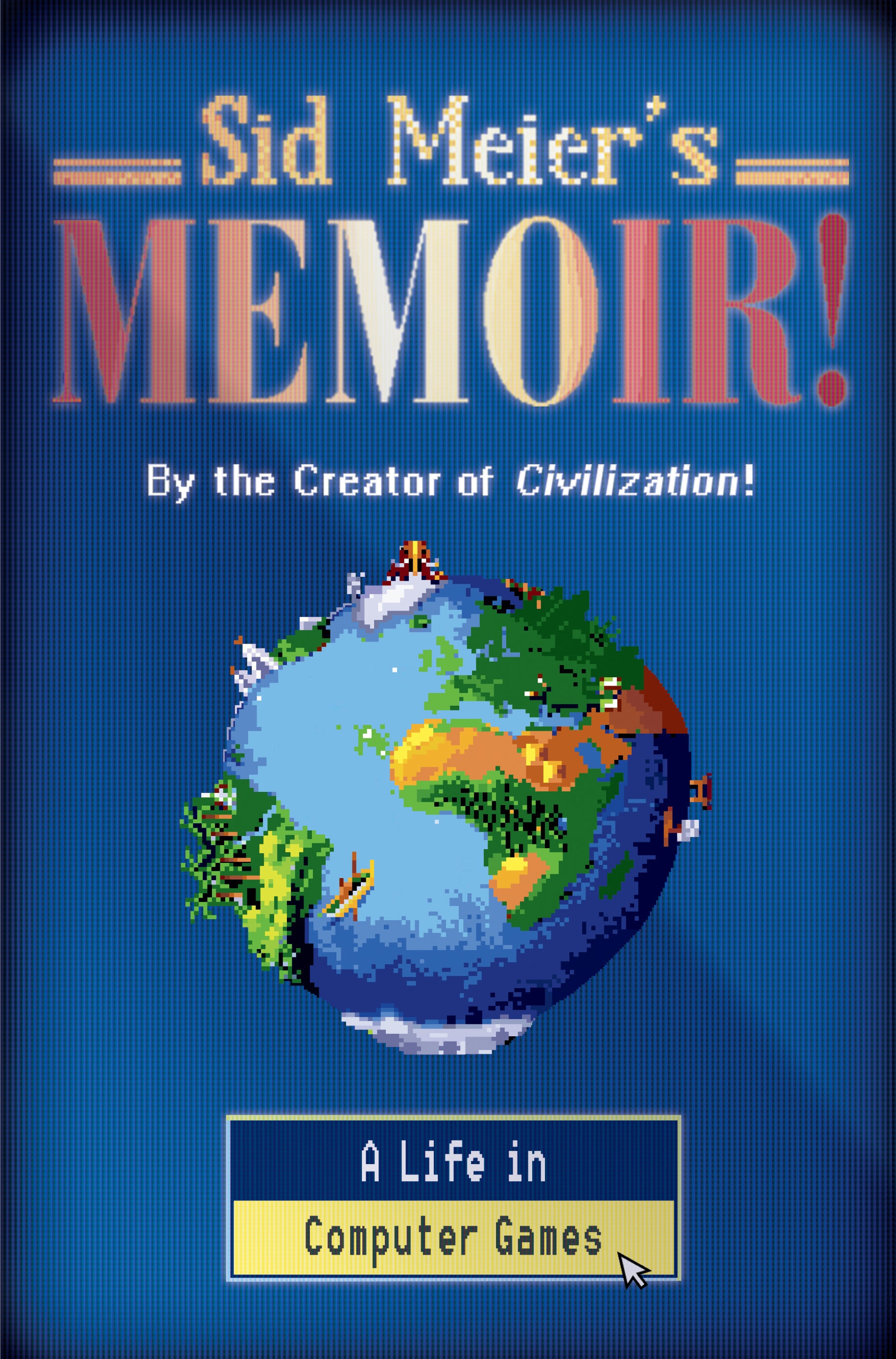

At 66, after nearly 40 years in the field, Meier has written an entertaining autobiography. Its title is Sid Meier’s Memoir!, the jaunty exclamation mark in keeping with the style he’s used throughout his career. The book looks back on his career in chronological order, from the early days programming 2-D action games in his lunch breaks, to the multimillion-dollar projects he works on now, which have more in common with Hollywood blockbusters than his early work.

“There’s a whole new generation of gamers who’ve grown up knowing games their entire life,” he says, explaining why he decided the time was right for a book. “So for those of us who go back far enough to remember a time without games, it’s our origin story. A time when there was no internet, when everything wasn’t available instantly online. I wanted to put down those memories before they fade into the mists.”

As with Buster Keaton or Elvis, Meier’s work is inseparable from technological innovation. During the time he has been working, the possibilities of video games have expanded faster than in any creative field in history. When he started out, game design was a side hobby from his job designing cash registers. The industry grew up with him. Today it is worth more than $100bn annually, and still growing at around 10 per cent a year.

His initial travails seem quaint. Meier was relieved when fighter jets started using HUD instead of old-fashioned instrument panels, as it meant he no longer had to give over the bottom half of his screen to depicting dials and gauges. To prevent piracy, they would include codewords in the game manuals, whose file-sizes were too large to be easily distributed.

For all the new possibilities of photo-realistic graphics and online play, you get the sense Meier feels something has been lost, too.

“For a long time we were pushing up against the limits of what the computer could do,” he says. “We were trying to get the most out of the available hardware and then tap onto the players imagination to provide the rest. That was the art of game design, to provide that stimulus. You would imagine being a fighter pilot, or a pirate, or the king of a great civilisation.” Where some games are more like films, gorgeous to look at but where many of the artistic decisions have been taken for you, Meier’s games are more like novels, inviting the reader to fill in the gaps.

Meier made his name with flight simulators in the 1980s and then with Pirates! in 1987. It was Civilisation, however, whose first iteration came out in 1991 (there have now been 12 editions), that ensured his place in gaming history.

For a long time we were pushing against the limits of what the computer could do

Civ, as it is known, put you in the role of the deity-type leader of a great civilisation. Beginning in 4000BC, you take control of a single settler in the centre of a large and mainly obscure map. You found a city, which you can use to make more settlers, or soldiers, and research new technologies to expand and advance your civilisation. World Wonders confer unique advantages to your civilisation: Stonehenge, the Sistine Chapel, or Angkor Wat.

The action is turn-based, so you have as long as you want to decide what you want to do as possible before you press “next turn” and your opponents make their moves.

The “next turn” button is the key to Civ’s magnetic hold on players’ attention. Who knows what will happen when you push it? There’s always another turn. Minutes become hours, hours become days. You settle down for a quick game at bedtime and before you know it the sun is coming up and you are being nuked by Gandhi. You can win militarily, or technologically by building a spaceship, or by amassing wealth. Different governments confer different advantages. Democracy is better for scientific progress and commerce, but makes it harder to wage war.

The game has been criticised for tending towards a liberal-democratic worldview, especially in its early incarnations, and has been cited in academic papers. In 2012, a story came out about a man who had been playing the same game of Civilisation 2 for more than 10 years, taking the game year up to 3991AD. His world had become a perpetual war between three perfectly balanced powers, endlessly dropping atomic bombs on each other. The story was picked up around the world, not least for its accidental similarities to George Orwell’s vision in 1984.

“We try to caution people about drawing too many parallels with the real world,” Meier says. “It’s a sandbox where you can do what you like. We’re trying to give you a broad brush appreciation of different leaders and philosophies, but not more than that.”

Despite its near-infinite replayability, Civ is not as easy to pick up and learn as many of today’s popular phone or console games. In the book, Meier reminds us that the bestselling games of 1998 were Civ 2, Warcraft II, Myst, Command & Conquer and Duke Nukem 3D. Aside from the last, all require more thought and engagement than the Candy Crushes or Fortnites that dominate gaming today. The competition for eyeball time means it’s hard to imagine those titles having the same kind of popularity if they were released now.

We try to caution people about drawing too many parallels with the real world

“I don’t think I could make Civilisation today,” Meier says. “I’m not sure even I would play it. It wouldn’t fit in the zeitgeist. It asks a lot of the player, and takes a while to work it out. You have to play it once in order to understand what's going on. You have to be willing to spend time with it, and that’s not where most gamers are these days. Civ came out at the perfect time. The PC had got beefy enough for us to make it, but weren’t inundated with so many possibilities. If it had been created two years earlier we’d only have had four colours and it would have been much shallower.”

The “addictiveness” of Civ is usually spoken about in affectionate terms, its worst expression a laptop slammed shut at dawn, but in recent years the dark side of gaming addiction has become a controversial topic.

Meier would encourage us to believe the “one more turn” side of his creation is about storytelling. But there is a dopamine hit, too. Gaming and social media companies have spent billions of dollars engineering their products to stimulate us. You might learn more about history from playing Civ, but isn’t it fundamentally hitting the same spots?

“[Addiction] is not a word I would use [to discuss his games],” Meier says. “We prefer to talk about engagement or commitment.” I can imagine the people who run casinos in Vegas making a similar argument, I say. “I’m not going to acknowledge that,” Meier replies. “We tend to think the time is well spent. You exercise your brain, and learn a little more about the world, and perhaps pique your interest in a new subject.” The memoir’s cover features praise for Civ from both Mark Zuckerberg and Satya Nadella, the Microsoft CEO.

As games have become more complex, the kinds of computer engineers who might once have gone into games have found themselves drawn to big tech, working on real-world applications. Much of the early research into what we now call “AI” was in computer games, to create opponents who could give you a game. Demis Hassabis, the founder of DeepMind, started his career in games, writing the code for Theme Park when he was in his teens. Does Meier ever wish he’d gone into broader tech?

“I think I have the best job in the world,” he says. “There’s always another game to be written. When I meet people who’ve played them and want to share their stories, with me, or with other players, or their children, I realise we can justify the billions of hours people spend playing. It’s about stories.”

Sid Meier’s Memoir! is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments