The strongest wave yet of female action heroes

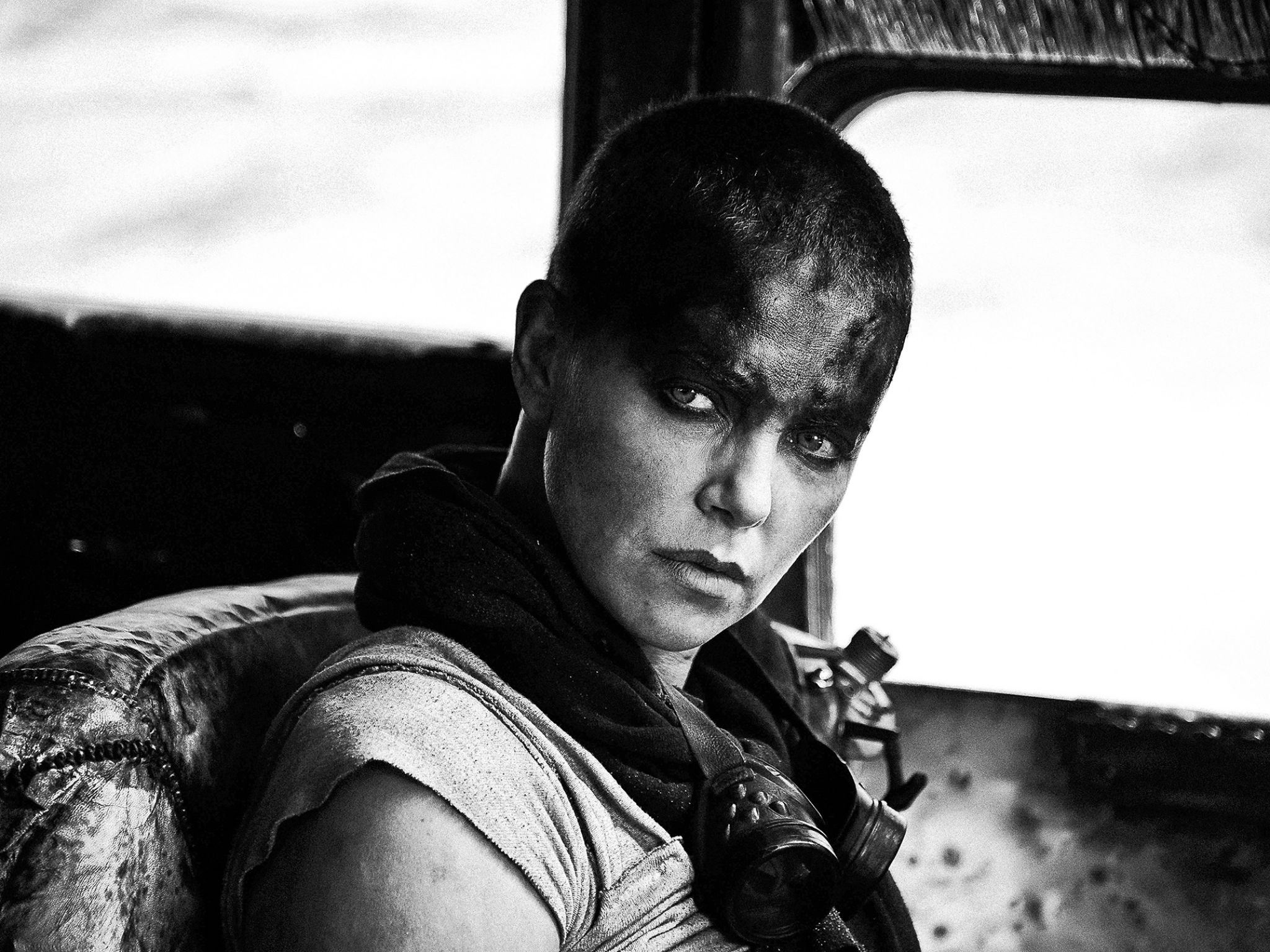

In the year of ‘Wonder Woman’, ‘Ghost In The Shell’ and ‘Alien: Covenant’, and in the wake of Charlize Theron’s roles in ‘Atomic Blonde’ and ‘Mad Max: Fury Road’, cinema’s current women are tougher than ever, says Nick Hasted

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“I don’t want to look like a guy and I don’t want to fight like a guy,” Charlize Theron told Vogue about her role in Atomic Blonde. “I want to fight like a woman.” As Cold War MI6 super-spy Lorraine Broughton, Theron accordingly dismantles every man who gets in her way while wearing six-inch heels, suspenders and a Galliano white trench-coat. She deliberately emphasises both her femininity and ferocity. In the year of Wonder Woman, Ghost In The Shell and Alien: Covenant, and in the wake of her own role in Mad Max: Fury Road, Theron is part of the strongest wave of female action heroes yet.

In Atomic Blonde, she fights with authentic desperation, mouth gaping and clenching with effort, eyes swelling shut, highly trained yet animalistic. There’s no stunt double during her seven-and-a-half-minute takedown of a KGB hit-squad, as she battles men with techniques which counter their physical advantage.

She brings all her Oscar-winner’s intensity to breaching this formerly male action preserve, and is bruised purple all over afterwards, broken but unbowed. Wearing heels while doing so was costume designer Cindy Evan’s idea, to show Broughton is definitely not Bond. They’re no less realistic than Daniel Craig’s patent leather shoe-sporting dash across an icy lake in Skyfall. Both films are fantasies. Atomic Blonde, like Wonder Woman and Jodie Whittaker’s Doctor Who, just makes its empowering object female.

This change ripples into other, subtler ones. Director Patty Jenkins and star Gal Gadot make Wonder Woman a graceful innocent who fights for love, emphasising her strength in soft ways which would scare Superman. Scarlett Johansson’s Major is also innocent yet implacable in Ghost In The Shell, projecting strength while essentially naked, in an otherwise hollow film.

Katherine Waterston’s ship’s officer Danny in Alien: Covenant is the nearest to a gender-blind role. Her realistic moments of terror and panic, though, reverse the progress of Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley from Alien’s vest-wearing ingenue to Aliens’ armoured soldier. Theron’s Imperator Furiosa in Mad Max: Fury Road makes the most successful stand. Not only female but one-armed, her single-minded need to save other women and find her way home lets her battle Tom Hardy’s Max almost to a standstill, and quietly become the film’s lead for as long as she’s in it.

The ability to dominate with violence defines most male film stars. From Clint’s Dirty Harry to Tom Cruise in Mission: Impossible, they keep their box-office coasting by blowing people away. Weaver’s Ripley is the only female equivalent, as the new action heroines are acutely aware. “Having a franchise with a female protagonist driving it is such a rare opportunity,” Johansson told Marie Claire of Ghost In The Shell. After wasting half a decade doing not much as the Black Widow in The Avengers, she’d know.

Theron is more vocally frustrated by Hollywood’s narrower apertures for female success. “We’ve had moments like this, where women really showcase themselves and break glass ceilings,” she told Variety, placing Wonder Woman in the context of Weaver, and Linda Hamilton’s warrior mother Sarah Connor in Terminator 2. “And then we don’t sustain it. Or there’s one movie that doesn’t do well, and … no one wants to make a female-driven film.”

Fuelling her fears, Ghost In The Shell and Alien: Covenant both stuttered at the box-office. Atomic Blonde is doing decently, but only had a $30 million budget (the same as its director David Leitch’s Keanu Reeves vehicle John Wick, but too little after Theron’s Mad Max impact). In each case, it’s the films, not their protagonists, which are flawed.

Passing box-office trends are anyway less important than positive changes in the way women see women on-screen. The slow progress to action cinema’s centre-ground began with female, essentially diminutive versions of male heroes, from Tarzan’s Jane to his female rip-off Sheena, Queen of the Jungle. The Western had its semi-fictionalised sharpshooters such as Annie Oakley and, most importantly, Marlene Dietrich as saloon singer Frenchy in Destry Rides Again (1939). Although Dietrich was determined to make a catfight with Una Merkel memorably realistic, this was played for comic effect, and became the staple, derisory form of female cinema action for decades to come.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

The line leading to cinema’s current tough women can be traced through the Sixties’ female answers to James Bond – Honor Blackman’s Pussy Galore in Goldfinger (1964), Monica Vitti in Modesty Blaise (1966) and, best of all, Blackman’s replacement in The Avengers TV series, Diana Rigg’s Emma Peel. Rigg deployed all her wry intelligence and amused sexuality, as her fight scenes defeated men and women with rough martial arts which the character clearly enjoyed. The fact that this was often achieved in a black leather catsuit was both practical and highly fetishised.

Still, with Rigg fully in on the joke, Mrs Peel was the first successful action heroine, with many subsequent cinema doppelgangers. In the Seventies, Pam Grier, though not really much of a fighter, then ennobled the “blaxploitation” action genre with fists-first, chin-up pride, bringing down Harlem pimps and the Roman Empire in the ripe pulp likes of 1974’s Foxy Brown (“If you don’t treat her nice, she’ll put you on ice”).

The weightless, supernatural martial artistry of Michelle Yeoh in Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) was the next real development, globalising a long-time Asian trend for more skilled, barely possible female fighting. Hollywood’s supporting heroines and villainesses paired off in similar, increasingly CGI-assisted style, as with Halle Berry and Rosamund Pike’s vigorous duel in the Bond film Die Another Day (2002), and Michelle Rodriguez’s increasingly dissatisfied role in The Fast And The Furious franchise.

Quentin Tarantino then fused all his love of classic Asian action into Uma Thurman’s Bride in the two-part Kill Bill (2003). I remember the gasps in the cinema during its opening scene, as Thurman’s quiet talk with Cottonmouth (Vivica A Fox) in her suburban kitchen explodes into a degree of unchecked, skilled, visceral female violence that was shockingly new.

In horror films the “last girl” who fights back against her psychopathic stalker, as immortalised by Jamie Lee Curtis in Halloween (1978), has gone similarly ballistic, topped perhaps by Sharni Vinson’s ex-survivalist character Erin in You’re Next (2013), whose determined, defensive rampage employs a head-mincing food-mixer against her luckless tormentors.

More realistically, real female progress in previously male preserves let women climb the ranks as police and military characters. Jamie Lee Curtis’s gruelling battle with psychopath Ron Silver and her police superiors in Kathryn Bigelow’s Blue Steel (1990) was more gripping than Ridley Scott’s GI Jane (1999), in which Scott enjoys would-be Special Forces soldier Demi Moore’s beating by her superior Viggo Mortensen a bit too much, before her eventual heroism under fire. Emily Blunt’s FBI agent in Sicario (2015) finds herself at risk from drug cartels during sex as well as on the Mexican border, but her gun-toting competence in action is beyond question by now.

Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001) meanwhile saw Angelina Jolie bring a pneumatic computer game caricature to life. The place of sex in such roles is made problematic by men from Jolie here to Atomic Blonde, in ways Indy Jones never worried about. Jolie for her part enjoyed her character’s exaggeratedly feminine body, wearing her thick wig and breast prosthetics off-set. She used her fierce charisma to burn through the role’s contradictions, making an otherwise mediocre film into a personally memorable, feminist adventure. The Lara Croft reboot due next year, with (like the computer game) a more normally proportioned Alicia Vikander in the lead, may show how far we’ve come.

For now, though, we have Theron, Johansson, Gadot and their partners in purging mayhem. Some could do with female screenwriters to fully free them from the tendency to make their characters secondary, even when they’re supposedly the star (does Steve Trevor have to save quite so much of the day in Wonder Woman?). Hollywood double-standards are a tougher opponent than KGB thugs or acid-blooded aliens. But in 2017, the fight is moving on.

‘Atomic Blonde’ is in cinema now. ‘Wonder Woman’ is out on DVD/Blu-ray in September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments