Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One of the final sequences in the new Disney/Pixar digi-mation involves the eponymous robot Wall-E failing to recognise his robot friend, Eve, despite the caressing touch of this latter's mechanical hand.

Now, would you be surprised to learn that I watched this little scene with tears pouring down my face? You oughtn't to be, because, as well as exhilarating, amusing, and just occasionally exhausting us, it is somehow now typical of those phenomenal wizards of invention at Pixar, led by writer/director Andrew Stanton, to have found a way of moving us, too. This studio is so good it's almost spooky.

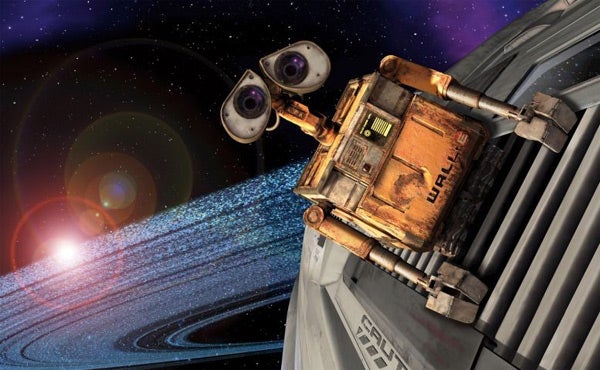

Wall-E is, among other things, a science-fiction fable, a love story, and a cautionary tale, but it is at its most ingenious, for the first half-hour at least, as virtually a silent movie. It's set in a nameless city, a desolate, dusty necropolis of trash where advertising billboards flicker uselessly and no living thing moves. This is Earth, 700 years in the future. The human race, having turned the planet into a rubbish tip centuries ago, abandoned it and went to live in space.

"No living thing" is not quite right. A small robot diligently trundles through the bleak, unpeopled, streets, sweeping up armfuls of rubbish, compressing it into tidy cubes, and stacking them in tall towers. This plucky gizmo is a Waste Allocation Load Lifter Earth-Class – Wall-E, for short. Whatever it (or, rather, he) doesn't compact into cubes he takes back to his den, a grotto of lovingly preserved junk.

He's an Autolycus of trash, you see, snapping up unconsidered trifles to keep himself entertained. His ancient VCR plays, over and over, two musical numbers from Hello, Dolly!, and what most fascinates him is the close-up of a boy and a girl holding hands as they dance together.

Wall-E is, like Crusoe on his island, a lonely creature. True, he has a pet cockroach that skitters around in his wake, but it's hardly the companionship he yearns for. And what sort would that be? We find out when an Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluer – Eve – falls to earth. White and sleek and ovoid, Eve doesn't respond to the grubby, angular Wall-E's overtures of friendship, too busy searching for the green shoots of recovery that will bring back the Earthlings from exile. At this point you ask yourself: what's the film going to do for dialogue? The answer is almost nothing. Two words only pass between these automatons: he learns to call her "Eva", and she calls him "Wally". Yet, spoken in varying tones of exasperation, puzzlement, dread and entreaty, those two words become all they need.

Like the old silents, Wall-E becomes a masterclass in non-verbal communication, conducted with all the expertise, wit and precision for which Pixar is now a byword. Just look at the way pathos is balanced on the angle of Wall-E's eyes, their lids like old-fashioned bicycle lamps. Look at the way he tests out a ping-pong ball and bat, or sizes up a diamond ring in its velvet box, or shows his new friend, Eve, the joys of popping bubble-wrap. These are tiny squiggles of detail, but are so delicately conjured and beautifully integrated that the film approaches the level of achievement of the Toy Story films, or the last great Pixar, Finding Nemo.

That it doesn't quite reach that plateau of fabulousness is down to its second half, which transports Wall-E and Eve back to Axiom, a luxury spacecruiser where a large army of 'bots service humans whose brains have turned as soft as their bodies; to put it another way, they're obese morons, reduced to lolling on their hover-chairs because automation has cancelled their need to walk, or even reach across a table for food. (I was reminded of a recent English novel that described America as "just people in huge cars wondering what to eat next".)

There's a not-so-understated moral here about a race that has pampered itself to death; though, in the character of the ship's captain, dissatisfied with the sterility of life aboard his vessel, one discerns the faint hope that human beings will begin to change their ways – if only out of boredom.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

"I don't want to survive," he says. "I want to live!" It's fair to ask at this point whether children, superbly entertained by the adventures of Wall-E, would be quite as enthralled by this mood of existential unease. Praise Pixar for trying to raise the stakes, but the longer the film goes on the more one appreciates the impact of that amazing first half-hour.

The temptation to piggyback popular culture is, for the most part, heroically resisted. Only when the film enters its climactic stage does it look to movie references for traction. The quick nod to Titanic is, I presume, for the kids; the discovery by the captain that his ship's computer has turned malign is a homage to Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, and could surely only be intended for adults. It's a harmless borrowing, really, and fits with the admonitory tone of the second half, but its effect is to set you wondering when Wall-E will take centre-stage again.

The paradox here is that the human characters feel far less interesting and complex than the robot ones. But that's Pixar: loving the alien.

The movie is preceded by a short, Presto, about a Victorian magician, his rabbit, and their fight over the ownership of a carrot. It has a careening slapstick violence worthy of Tom and Jerry, lasts about five minutes, and might be one of the cleverest things that even Pixar has pulled out of its magic hat.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments