The Big Short, film review: The financial crisis film it's OK to laugh at

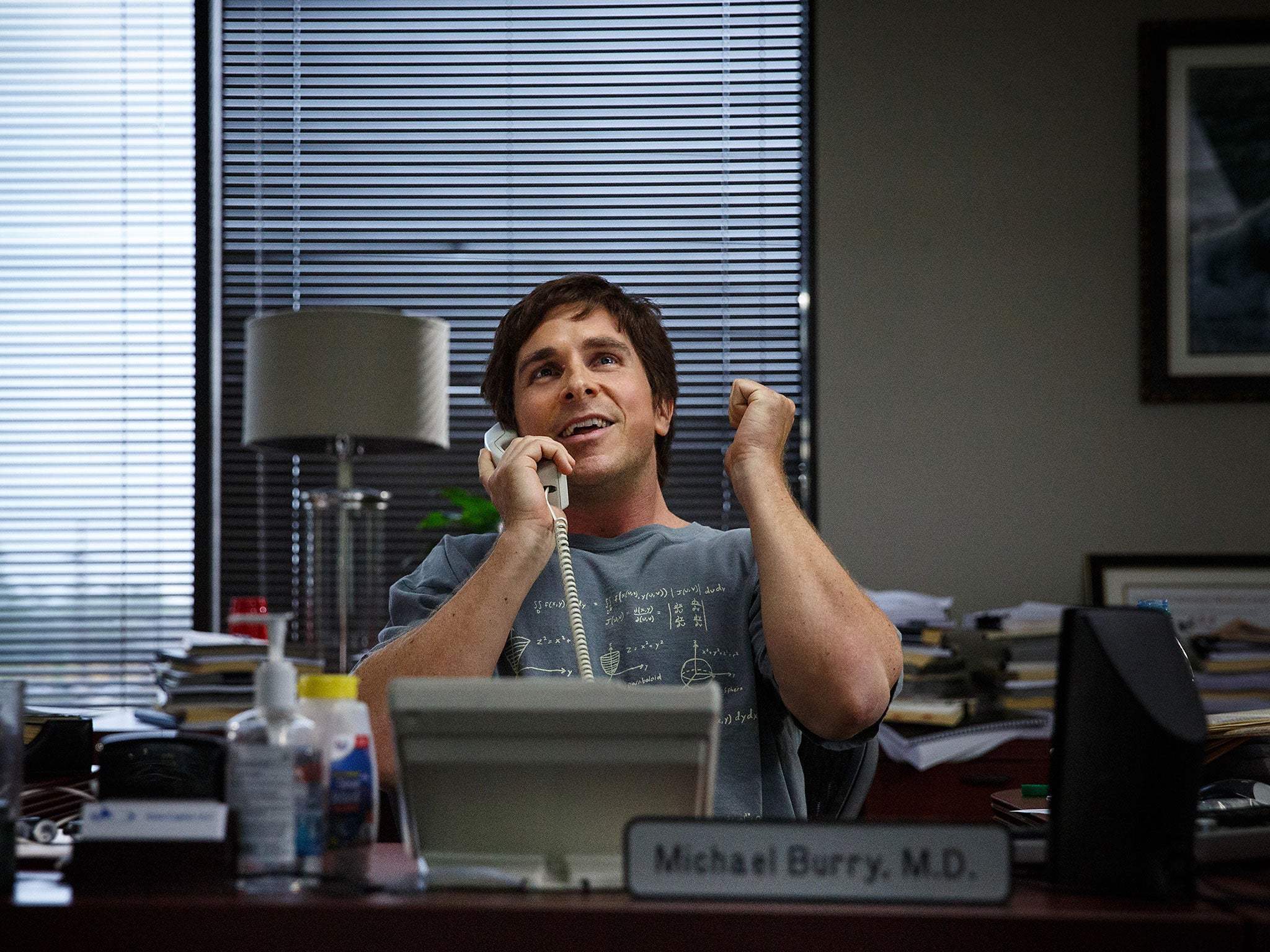

(15) Adam McKay, 130 mins. Starring: Christian Bale, Steve Carell, Ryan Gosling, Brad Pitt, Marisa Tomei

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is an economics festival in Kilkenny, Ireland, at which the idea is to mock banking and political figures while "waiting for answers". The trick at Kilkenomics is that the experts are interviewed not by specialists but by comedians. This encourages them to communicate in a way a general audience can understand. A similar thinking underpins Adam McKay's raucous comedy, which manages the unlikely feat of being wildly entertaining while telling a complex and ultimately depressing story.

The film, adapted from the Michael Lewis book The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine, is about the events leading up to the US subprime mortgage crisis and the implosion of the global economy in 2008. This isn't really a subject for laughs but McKay treats it as the stuff of high farce.

McKay (best known for his collaborations with the comedian Will Ferrell on Anchorman and Step Brothers) is dealing with material that many American economists and bankers themselves failed fully to understand. The film is full of references to credit default swaps and collaterised debt. McKay helps the audience understand such esoteric matters by taking a jaunty, tongue-in-cheek approach. Every time there is an especially complicated piece of information or financial jargon, he will throw in an interlude in which a celebrity (Selena Gomez or the chef Anthony Bourdain; or, fresh from The Wolf of Wall Street, Margot Robbie) will talk direct to camera to explain it. Sardonic voiceovers sketch in the background history of a system so warped that it eventually led to penniless Florida strippers "owning" (or at least having mortgages on) multiple properties. As the film points out, the language of high finance is deliberately obfuscating. The public isn't supposed to understand it. The irony is that, for a lot of the time, the bankers clearly didn't, either.

The "heroes" of the film are the outsiders who take the time do the maths. The paradox here – one the film can't quite resolve – is that most of them are motivated by the same basic instinct, namely extreme avarice, as the bankers who made such a mess of the American economy. They see an opportunity of cashing in when the housing bubble bursts. There are references here to foreclosures as well as an ominous shot in which we see an alligator in a condo swimming pool but this isn't a film that pays much attention to the suffering of "ordinary" Americans. To focus too closely on that would be to risk undermining the comedy.

You can't help but suspect the film-makers are compromised. This is a movie made by a Hollywood studio owned by a company on whose board have sat some of the bankers the film is trying to harpoon. Even so, the contradictions are part of the appeal. The protagonists are very different from the masters of the universe in The Bonfire of the Vanities or Oliver Stone's Wall Street films. They're eccentric, querulous and sometimes foul-mouthed oddballs, most of them played by Hollywood A-List stars slumming it. There are no Gordon Gekkos here and greed most certainly isn't good.

In a brilliant character performance, Christian Bale takes the tortured loner routine he developed playing Bruce Wayne to new extremes. He plays Michael Burry, a California-based hedge-fund manager. Burry is a T-shirt-wearing beatnik-type with minimum social graces who spots before almost anyone that the housing market is "propped up on bad loans". By the laws of economic gravity, it is bound eventually to tumble down. His own investors dismiss him as a crackpot but he is dogged in his determination to short the market.

Steve Carell is equally distinctive as hedge-fund manager Mark Baum, a pessimistic and "p****d off" figure who sees a chance to avenge the indignities the American people have endured at the hands of the banks. He is the one character for whom this is a moral crusade rather than a chance to make money. His attitude is different from that of the shamelessly opportunistic Wall Street trader and city slicker Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling in Mephistophelian mode). Then, there's the bespectacled and reclusive former banker Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt, who co-produced) acting as mentor to two small-time traders who've also spotted the impending calamity in the housing market. As the world's economy is about to collapse, Pitt's character sits in an English country pub, using his laptop to facilitate trades worth millions as the locals curse him.

McKay combines goofy comedy with moments of caustic satire. There is a tremendous scene in which many of Wall Street's most senior, self-important figures are in a conference theatre, waiting for a debate about the housing market. When their Blackberries start buzzing, they realise their banks are in trouble and scurry for the exits, dignity in shreds. Equally striking is a surreal interlude in which Baum and his staff head to Florida to do their research on the housing bubble. They encounter a Sunshine State in which no one has money and unemployment is rife – and yet everyone seems to own strings of properties and can borrow money at will to buy more. Toxic loans are bundled into packages, sold on, re-classified and given triple-A ratings by credit agencies.

What makes the collapse, when it happens, so startling is the collision between the bankers' abstract formulations and the hard reality of families losing their homes. The film-makers play with our sense of expectation. We want the heroes to be vindicated, yet we realise their success will mean disaster for the economy.

The film ends in witty but downbeat fashion. It's hardly a spoiler to point out that little has changed since the 2008 housing crash and financial crisis. On the basis that the story would be simply too depressing otherwise, McKay accentuates the comedy that goes hand in hand with the incompetence and corruption – and that's why The Big Short is one disaster movie in which it is always safe to laugh.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments