I Am Not Your Negro review: Lets James Baldwin's searing work soar

I Am Not Your Negro isn't as pessimistic as its downbeat tone suggests it should be. Baldwin's commentary is intended to provoke, not to induce despair

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dir: Raoul Peck, 94 minutes, featuring: Samuel L Jackson (voice), James Baldwin, Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, George W Bush, Dick Cavett

You may not agree with all the (very bleak) conclusions American writer James Baldwin reaches in I Am Not Your Negro, but you will be astounded by the searing brilliance of his polemic.

Late in his life, Baldwin, who died in 1987, wrote an unfinished manuscript called Remember This House in which he told the stories of three of his friends who died before they reached 40: Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers. All three were murdered between 1963 and 1968. With their deaths as a starting point, Baldwin spun an analysis of race, class and bad faith in America.

“I want these three lives to bang against and reveal each other, as, in truth, they did,” Baldwin tells us. Director Raoul Peck has created a documentary around Baldwin’s manuscript (with his voice supplied by Samuel L Jackson).

Peck has also assembled footage of Baldwin talking about race and politics on TV shows and from a televised 1965 debate, “Has The American Dream Been Achieved At The Expense Of The American Negro”, staged at Cambridge University.

Alongside the footage of and narration from Baldwin, Peck includes more recent material: the police beating of Rodney King, the violence in Ferguson, and references to Obama’s America. There are also clips from the Hollywood movies that Baldwin watched enraptured as a child. We see Joan Crawford dancing in the 1930s musical Dance, Fools, Dance.

She may have been a “white lady”, but Baldwin adored her, just as he did John Wayne and Gary Cooper in the old westerns he used to watch before he realised that, as an “American Negro”, he was one with the Indians the cowboys were so busy killing off.

Some of the juxtapositions here seem a little simple-minded. It’s unfair on Doris Day to use her as the quintessential symbol of post-war, pampered, white, middle-class America – of families behind picket fences enjoying luxury filled lives, oblivious to the suffering of black Americans. It’s a lazy and stereotyped picture of Day that doesn’t even begin to acknowledge the complexities of her career.

It’s hard, too, to understand why Billy Wilder’s romantic comedy Love In The Afternoon, starring Gary Cooper and Audrey Hepburn, is cited as an example of white complacency. Generally, though, Baldwin is probing and acute in his observations of the way that white Americans try to ignore the racial violence in their own society. He talks of their “moral apathy” and of their immense capacity for self-delusion.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

When the “white liberal people downtown” watched Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier as the escaped convicts in The Defiant Ones, they cheered when Poitier’s character jumped off the train rather than leave the white man behind. Black people, Baldwin suggested, responded to the scene in a very different fashion. They couldn’t understand Poitier’s behaviour and thought him a fool for not saving himself when he had the chance.

Baldwin and Peck are both alert to the contradictory behaviour of white liberals. The liberals often seem very moved by Baldwin’s rhetoric. The undergraduates in their tweed jackets at the Cambridge Union give him a standing ovation. The TV hosts are always respectful of him, even when they’re very wary (as Dick Cavett was) of his trenchant analysis of race relations.

The film includes a montage of apologies in which white politicians are shown on camera saying “sorry” for past misdeeds, but Baldwin argues they can’t really bring themselves to overcome their own blindness or cowardice. They’re not ready to “face and deal with and embrace” the “stranger” they’ve “maligned so long”. The author is withering in his analysis of the church, citing Malcolm X's point about white and black Christians being so divided that "noon on a Sunday" is one of the most segregated moments in American life.

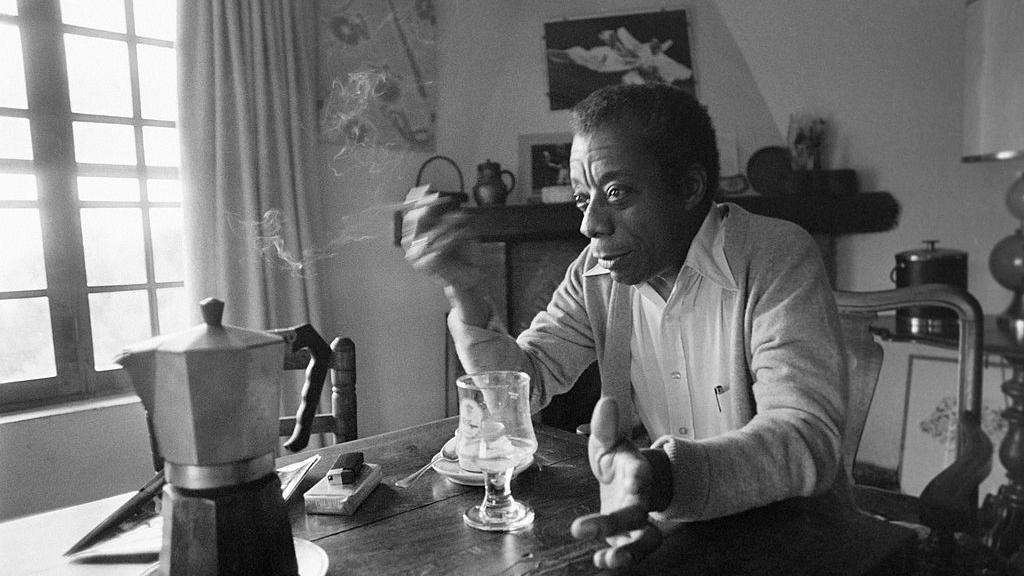

One reason that Baldwin makes such a compelling screen presence is that he’s not a politician or civil rights leader. He is an artist, a bit of a dandy who left Harlem to live in Paris. He comes at social and political issues from a poet’s perspective. Peck has done him an enormous service by turning his 30,000-word unfinished manuscript into a feature documentary.

The archive footage and the contemporary references give it a heft it wouldn’t otherwise have had. I Am Not Your Negro credits Baldwin as its writer but Peck has shaped the film and has edited together Baldwin’s text and the commentaries from his TV appearances in an exceptionally skilful way. The film’s conclusions aren’t reassuring. “The story of the Negro in America is the story of America. It is not a pretty story,” Baldwin states. “To look around the United States today is enough to make prophets and angels weep.”

Baldwin was writing more than 30 years ago. Not so much has changed since then. Even so, I Am Not Your Negro isn't as pessimistic as its downbeat tone suggests it should be. Baldwin's commentary is intended to provoke, not to induce despair.

‘I Am Not Your Negro’ is out in UK cinemas on 7 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments