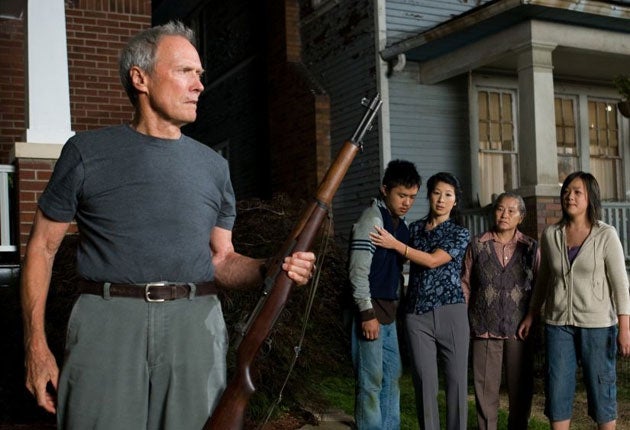

Gran Torino, Clint Eastwood, 117 mins, 15

The screen legend plays an angry old man at war with the city of Detroit

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You could be forgiven – though probably not by the man himself – for doubting whether Clint Eastwood is really an actor. With a range that’s not so much limited as, let’s say, specialist, Eastwood is at once an irresistible force and unmovable object, rooted in the screen like a gnarly, unbendable tree. More than any Hollywood actor alive, he is what he is.

And Eastwood is most what he is when directing himself. I have huge respect for his films in which he chooses not to appear, but it’s hard to feel much love for them. When he’s in front of his own camera, that’s another matter – and I’d take even a dud Eastwood-shoots-Eastwood film, such as the daft thriller Absolute Power, over one of the academic prestige pieces he makes when wearing his auteur Stetson: earnest, tendentious stuff like the recent Changeling.

In Gran Torino – which he’s said will be his final role – Eastwood is back on both sides of the lens, and that’s always good for him: he knows how to expend the least energy necessary in the two jobs. Not that there’s anything remotely Zen about his performance here: the intensity is always visible, but it’s all tightly contained around his jaw and neck muscles. In one scene, Eastwood’s character loses patience with his family and he just snarls at them. The camera closes in around his head and shoulders; the brows knit like tensed cable; the teeth clench and he emits a growl, a proper get-away-from-my-kennel growl, like the bulldog in Tom and Jerry. In fact, if Eastwood had done nothing but give close-ups of himself as a growling head, Gran Torino would still have been riveting. As it is, he’s turned in a terrific, taut, no-frills drama, with the kind of provocative social content that we’ve come to expect from Hollywood’s most unpredictable conservative liberal (or liberal conservative).

Eastwood’s character is Walt Kowalski, a retired Ford worker and Korea veteran. Newly widowed, Walt hates everyone: his spineless, selfish family; the baby-faced priest (a very watchable young actor, Christopher Carley) who’s tenaciously out to save his soul; and the various ethnic groups that now dominate the Detroit suburb where Walt feels like the last bastion of the white working man. Walt is especially tetchy about the family next door, unspecified “gooks” to him – in fact Hmong immigrants, belonging to a widespread ethnic group from across South-east Asia.

Walt tangles with the family’s shy teenage son Thao (Bee Vang) when the kid – pressured by his gang-leader cousin – tries to steal Walt’s pride and joy, the 1972 Gran Torino in his garage. But the old bigot eventually warms to Thao’s street-smart sister Sue (Ahney Her), then to her family, and sets about both disciplining and educating the boy. That involves setting him a course of boot-camp DIY, finding him a job, and teaching him “how guys talk”: this in a magnificently foul-mouthed scene with John Carroll Lynch as the local barber, a showerbath of racist invective in which Thao gets the priceless punch line. And naturally, Thao and Sue re-educate Walt in return.

Written by Nick Schenk (story credit shared by Dave Johannson), Gran Torino has been read by some as Eastwood’s belated reparation for the vigilante ethic he embodied in Dirty Harry – although as a thoughtful humanist, Eastwood the director balanced the books long ago. But certainly, Walt Kowalski offers a sour portrait of how a Harry Callahan might end up. Throughout, the film seems to cater to the old-school Eastwood fans, who would love to see a cussed old white conservative getting his gun and sorting out the whole damn hell-in-a-handcart situation of America today. Several scenes give us just that, the fearless patriarch seeing off African-American and Asian gangs alike with his contemptuous glare: nothing less than an ancient God of Disapproval.

In the end, things build up to the showdown, Walt’s personal OK Corral. Gran Torino is, of course, a contemporary Western, although the Wild Frontier is no longer an America under construction, but an urban America that’s been allowed to fall into disrepair by successive governments.

However, the film proves to be about alternatives to prejudice and vigilantism: as in his great 1992 Western Unforgiven, Eastwood has made a sometimes violent film that is also a disavowal of violence. Gran Torino is also a modest anatomy of American racism. Admittedly, the Asian characters play a largely instrumental part in correcting Walt’s complexes, and you can’t deny the stereotyping: studious son, hip sassy daughter… But at least the film takes a genuine interest in its ethnic background: when did a Hollywood movie last bone up on the Hmong? And in fairness, the stereotyping works across the board, with white suburbanites coming off worst: Walt’s bland bourgeois son and sullen granddaughter with her nose ring and mobile. But Eastwood might reply that all this is less stereotyping, more getting the job done with a couple of basic brush strokes – and who would argue?

As usual when he’s also acting, Eastwood’s direction is brisk, clean cut, to the point: a let-me-show-you-how-it’s-done-godammit sort of job. The film’s prosaic look is spot-on: photographed by Tom Stern, this sleepy suburban backwater, with its dried-up front lawns, has the look of an abandoned war zone, faded khaki tones suggesting that combat could erupt at any moment.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Eastwood is one of the handful of veteran Hollywood leading men who have dared to be old on screen, as opposed to acting the lovable old-timer. Like Wayne, Mitchum, Newman before him, Eastwood turns in a late performance that shows how the ornery young hero becomes a dyspeptic old sod. He nicely leavens the severity with self-deprecating humour, but Walt’s grouchiness, verging on the sociopathic, isn’t just for amusing effect: it embodies a character sharply defined by a good script. Walt’s loathing of his own family, his reluctance to reveal his more complex emotions, the psychic damage he’s sustained from horrors both witnessed and perpetrated in Korea – all this is complex stuff that the script specifies, but that Eastwood fleshes out, for the most part with little more than a scowl and a simmer. And minimalism of that kind really is great screen acting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments