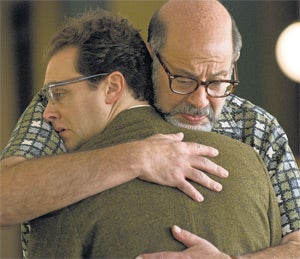

A Serious Man (15)

Their heart isn't in it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Is it possible to admire a body of work for its smartness, deadpan humour, irreverence, visual bravura, and yet feel thoroughly alienated and even dismayed by it at the same time?

In the case of the Coen Brothers' movies, I'm afraid that's a regretful yes. A Serious Man, their latest, is being touted as their most "personal" film, and its vision of a suburban Jewish community in Minnesota in 1967 has moments of laugh-out-loud verbal quirkiness to rank with the best they're capable of. But it also falls in line with the Coen shortcomings: a narrow emotional range, a patchiness of construction and a contemptuous refusal to seek meaning or revelation in anything. Comedy, even tragicomedy, should not feel like such hard work.

It plays out the story of a modern Job. Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg) is a physics professor in a quiet Midwestern university whose life has started to unravel before his eyes. His maladjusted brother is sleeping on the couch, hogging the bathroom and getting into trouble with the police. His son Danny (Aaron Wolf) is about to be bar mitzvahed but has dope on the brain, Jefferson Airplane on his transistor and "F-Troop" on the telly. His daughter (Jessica McManus) is stealing money from his wallet to save up for a nose job. Worst of all, his wife Judith (Sari Lennick) has fallen in love with a local widower, the maddeningly sanctimonious Sy Ableman, and wants Larry to move out of the family home.

Enough already, you may think, but the story keeps burdening its protagonist with woes. His next-door neighbour is a redneck hunter who plainly dislikes him. A decision on Larry's tenure is being undermined by an anonymous letter campaign, and a Korean student is trying to blackmail his way to better grades. As you wonder what the point of this victimisation might be, the unfortunate Larry goes to seek guidance from three different rabbis. Why has the "Hashem" – the divinity – got it in for him? Good question, but don't expect a serious answer. One of the rabbis tells an elaborate moral tale about "the goy's teeth", which turns out to have neither a moral nor a point. "We can't know everything," the rabbi shrugs. "Yeah, but you don't seem to know anything," Larry replies, not unreasonably. It's good comedy, as is the confusion over "the get" – a formal Jewish divorce – which becomes a running joke in the same way that the hula hoop ("You know, for kids") did in The Hudsucker Proxy.

They've got funny bones, these Coens, and it's heartening at least that their pictures really don't look or sound like anybody else's. But the laughter they induce isn't joyous, or cathartic, or instructive; it's mirthless, because the farcical situations they conjure are also essentially realistic, characterised by boredom, exasperation and anxiety. Even when Larry breaks out of his repressive shell and shares a joint with his foxy neighbour who sunbathes in the nude, there's no liberating sense of fun, because the Coens have decided that Larry is trapped – trapped emotionally, yet also trapped in the self-consciously formal style of their film-making, a matter of long silences, forlorn stares and abrupt close-ups (they seem to have a thing about ears in this film). It's a tribute to Michael Stuhlbarg's performance that we can bear to be in his company for so long without yielding to an urge to scream.

A Serious Man may be a "personal" film, but nothing in it suggests the Coens' affection for the era they grew up in, or a nostalgia for the faith they may have lost. The philosophical terminus is no different from any of their other movies: human existence is futile, and questioning your luck is meaningless. "I feel like the carpet's been yanked from under me," says poor Larry, whose fate looks sadly sealed. But it's not the indifferent universe to blame – it's his two indifferent creators.

Watch the trailer and clips from the film in the embedded videos

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments