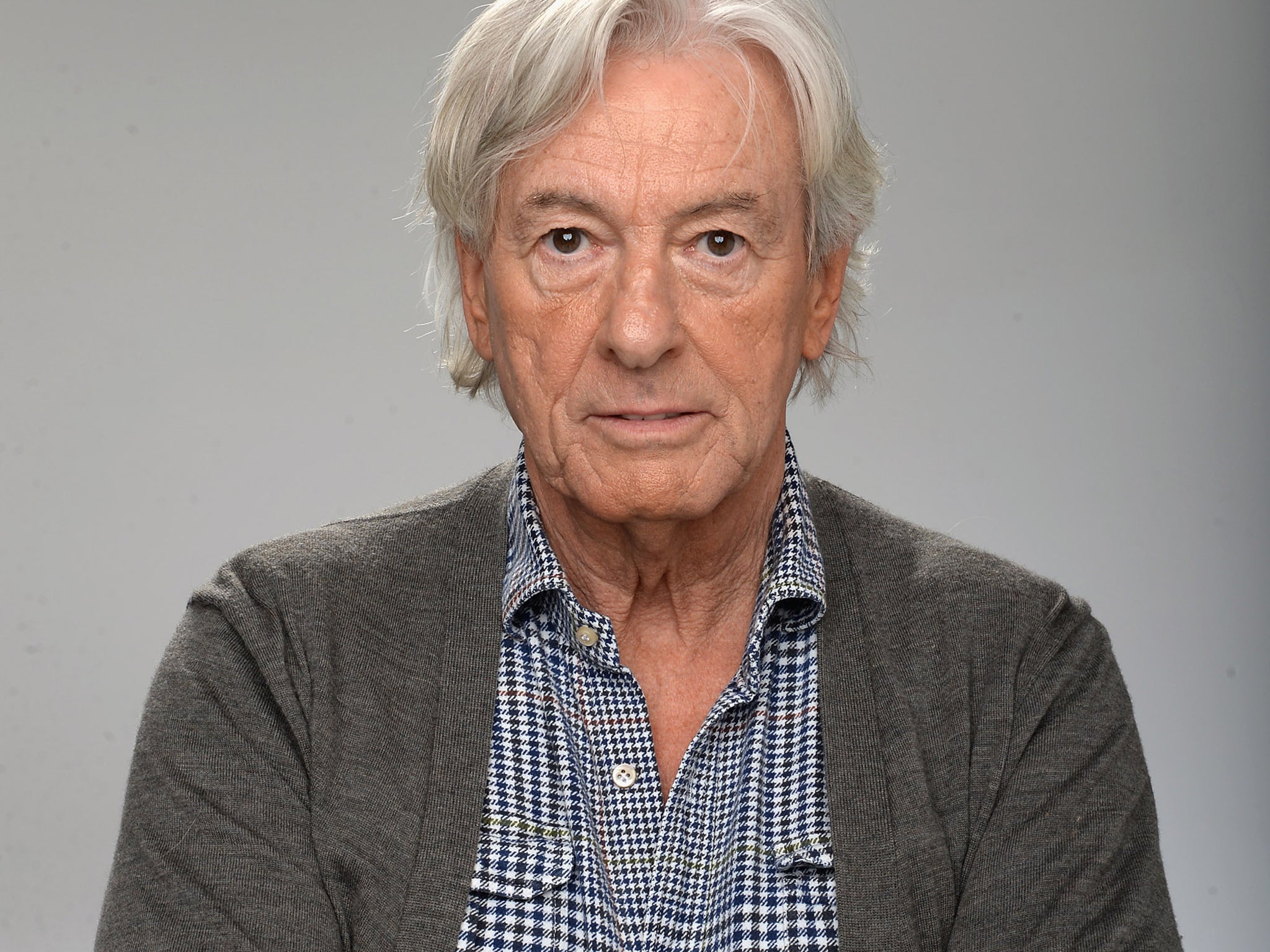

Paul Verhoeven interview: the director continues to stoke up controversy as his latest film premieres at Cannes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At the age of 77, Paul Verhoeven’s status as one of the bad boys of European cinema hasn’t diminished in the slightest. His new film Elle (premiered at the Cannes festival and the first movie has made in France) had stoked up plenty of controversy even in advance of its screening. In the film, Isabelle Huppert plays the victim of a violent sexual assault. Her assailant is masked (although she later discovers his identity). She reacts to the trauma in a way that will startle audiences.

Elle, Verhoeven is at pains to point out, is not a revenge thriller. It is something far more unsettling than that. “In the American way, it would be a revenge movie but it absolutely isn’t a revenge movie,” he says.

The Dutch director of Basic Instinct and Showgirls acknowledges that he is dealing with a taboo subject matter. In even touching on the subject of rape, he runs the risk of being called crass or misogynistic. Elle, he says, isn’t intended as popcorn entertainment; its themes are deliberately dark and ambiguous.

“I don’t see there is an enormous difference is showing a scene of torture or seeing a rape,” Verhoeven reflects. “I mean, Mel Gibson’s movie about Jesus is all about torture. Ultimately, the film worked very well, and was an enormous success. Do you call it entertainment? You have to see it [Elle] on that level. It is not entertaining what you see here. The rape is not entertaining on that way. I try to make the rape really shocking, in fact, as much as possible. It is very precisely choreographed.”

Verhoeven relied “very heavily” on the intuition of lead actress Huppert in setting the boundaries for what he could depict. “Her identifying with the character in such a powerful way is what makes the movie possible,” he says. “Whatever anybody might perceive as being politically incorrect is, in my opinion, wiped away by her.”

The director adds that he has never shied away from showing sex or violence in his work. “Of course, sex in general is one of the most important things in the world, isn’t it? And violence is the other. Sex in general is supposed to be creative and violence is destructive. But sometimes violence is necessary and sometimes sex can also turn into violence, as it is in this movie.”

In Huppert, Verhoeven found an actress as audacious as he was. The director gave Huppert licence to improvise. “I really strongly believe that it would have been very hard to find anyone else in the world who could do what she did,” he enthuses of the legendary French star.

When he was making Basic Instinct (1992), Verhoeven had more than 80 shooting days. For Elle, the schedule was about half that, but Verhoeven shot the film with two digital cameras and two separate cinematographers. He took a freewheeling approach. “These two camera were equal. There was no A camera and no B camera.” The idea was that two cameras would “dialectically talk to each other visually” and that there would be twin perspectives on every scene.

Working in France with a French producer (Said Ben Said, who has also produced films by Roman Polanski and David Cronenberg) appears to have liberated Verhoeven. Since he made Second World War thriller Black Book (2006) back home in the Netherlands, he has had many projects stall and collapse under him. He is no longer a bankable director in the way that he was when he was making films such as Total Recall and the notorious Showgirls. He can’t hide his frustrations as the way he has been treated by the Dutch film industry.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“I have the feeling that I am more respected in France than in Holland,” he sighs, citing the old biblical saying about prophets without honour in their own countries. “You’re too close-by, too close-by.” He talks of the continuous “sabotage” his projects have experienced at the hands of Dutch film funders and of how the Dutch consider his work as “decadent” and without “cultural value”.

In France, however, film is still regarded as an art, and directors such as Verhoeven are still cherished as auteurs. “It is wonderful there [in France],” he rhapsodises. “Culture is meaningful in a major, major way. Even government ministers think film is important,” he adds with a sense of wonder.

In Hollywood, by contrast, directors are a dime a dozen, almost as disposable as scriptwriters, while in the Netherlands, the idea that film could be considered as an art doesn’t seem to be accepted by anyone.

Verhoeven is already hatching several new movies in France with Said Ben Said. One is his long-gestating Jesus project, based on his own book. Another one deals with events in Lyons in 1943, when resistance hero Jean Moulin was given up to the Nazis and tortured by Klaus Barbie. In the film, Verhoeven will be dealing with the bad blood and betrayal between different resistance groups, again a subject likely to stir up controversy and bad feeling.

Another is a medieval drama set in a monastery and scripted by Jean-Claude Carri ère, the screenwriter of Luis Buñuel ‘s Belle De Jour (1967) and The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie (1972). Meanwhile, for TV, he is also plotting a modernised version of the Guy de Maupassant classic novel Bel-Ami that is being scripted by Gerard Soeteman (who wrote his early movies.)

In the old days, Verhoeven paid little attention to the irksome task of publicising his movies. He credits Arnold Schwarzenegger with setting him straight on that score. Now, he accepts that talking up a movie is almost as important as making it – at least, if you want it to reach an audience. That’s why he throws himself into interviews with an enthusiasm that would have been unthinkable only a few years ago.

Verhoeven’s career can be seen as a series of chameleon-like changes of identity. In the Seventies and Eighties, he was the angry young man of Dutch cinema. In the Nineties, he turned into the quintessential Hollywood director and insider. Now, he is reinventing himself as a French director – and it’s a new role that he relishes.

‘Elle’ premieres in the Cannes Festival this weekend and is expected to be released in the UK later in the year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments