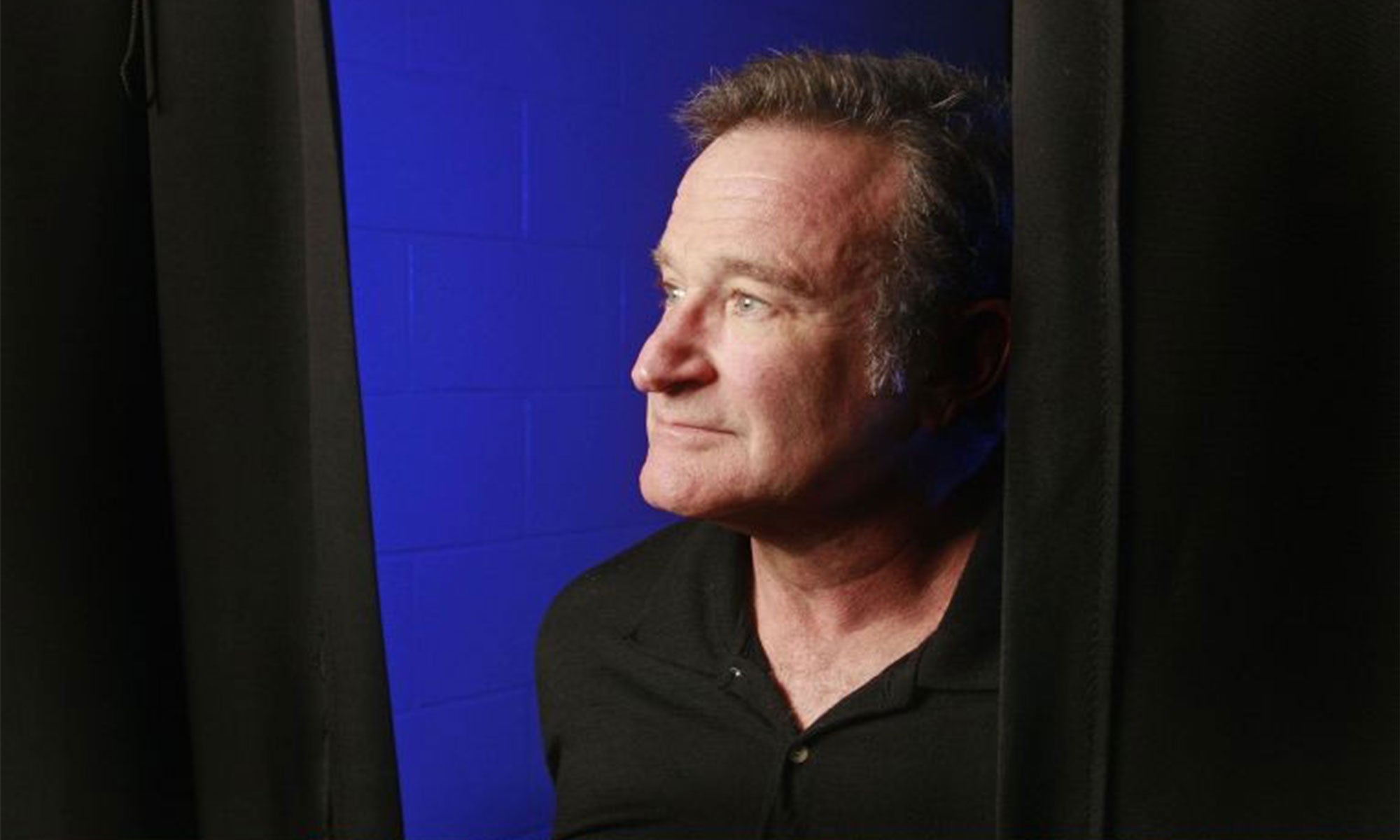

Robin Williams: Recalling an interview with a 'gracious, kind and genuine' movie star

When Ellen E Jones met Robin Williams in 2010, he spoke about his movies with an emotionally-intelligent humility

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One of the truisms about celebrity interviews is this: actors just starting out are usually a pleasure, because they’re not yet jaded. It’s stars on the next rung up, those who’ve been famous for a little while, who can be a pain. They’re the ones who turn up late, are rude, and are seemingly desperate to prove themselves deserving of the kind of adoration that no one could ever really deserve.

When I met Robin Williams in a Kensington hotel in 2010, he struck me as a great example of the third kind of celebrity interview: a proper movie star who’s been through the personality-distorting wringer of fame and escaped out the other side with a new-found humility. He was gracious, kind and genuine. He listened carefully to my questions and made an obvious attempt to answer them fully.

You didn’t have to beg him to do the voices, either. His own speaking voice was so soft, I had to lean forward to hear it, but he often broke into impressions - the genie from Aladdin, Michael Caine, HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey. I counted seven over the course of the interview.

Some comedians use humour as a means of working through their inner pain - so goes the “sad clown” cliche - but with Williams the almost compulsive madcap improvising seemed like a way to deflect attention away from himself.

He said he admired those comics who were braver: “I’m more kind of tentative about it, I’ll think, oh I can’t say that and then someone will talk about it honestly...I don’t talk about my own life. It’s not really personal per se and there’s other people where that’s their entire act.” He struck me as a little bit sad, but also sensitive, self-aware and emotionally intelligent. And he wasn’t just a clown either, he was a real actor.

By this point, he’d already been through a lot in his personal life. He’d been a cocaine and alcohol addict in the era when his good friend John Belushi died of an overdose. Then after 20 years of sobriety, he suffered a relapse in 2006 and checked himself into rehab. His brother died the following year, his second wife filed for divorce in 2008, and he needed emergency heart surgery in 2009.

He had also enjoyed great success. He was beloved for family favourites like Hook and Mrs Doubtfire, admired for critical successes One Hour Photo and The Fisher King, and also - let's be honest - mocked for a string of absolute stinkers - Bicentennial Man, Patch Adams, What Dreams May Come.

This was an issue my editor had asked me to broach in the interview and I was still trying to work out a way to do so tactfully when Williams sensed what I was about to ask and jumped in to spare me the awkwardness. “People ask, ‘Why did you make Old Dogs? Because it pays the bills. You’re just out of rehab. Good luck. You’ve got to get out there.”

Perhaps it was easier to be open about his sometimes pragmatic approach to making movies because he was there to promote a film of which he was truly - and justly - proud. In World’s Greatest Dad, Williams played an English teacher and single dad to a vile teenage son. When the son dies in tawdry circumstances, Williams’s character decides to re-frame the death as something heroic. It wasn’t one of those mawkishly sentimental films which, by this point, Williams was known for. It’s a film filled with real, complicated adult emotions, moments that are outrageous yet thoughtful, cynical yet heartfelt.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

This was also not one of the films he did to pay the bills, but one he did to help out a friend. Director Bobcat Goldthwait and Williams knew each other from their days on the stand-up circuit in the 70s and 80s, but Goldthwait had never had the same mainstream success. By taking the role, Williams allowed his friend’s film to get made. He was a nice man like that, obviously, but he was also a braver performer than he sometimes gave himsef credit for. World’s Greatest Dad was a chance to do something different. He took that chance and delivered brilliance.

That was my favourite performance of his, but in our interview he was never dismissive of his more famous family movies, either. He described once sneaking into the back row of a screening of Aladdin: “It was kind of like that moment in Sullivan’s Travels where I saw parents just laughing with their kids and I though yeah...that’s kind of sweet.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments