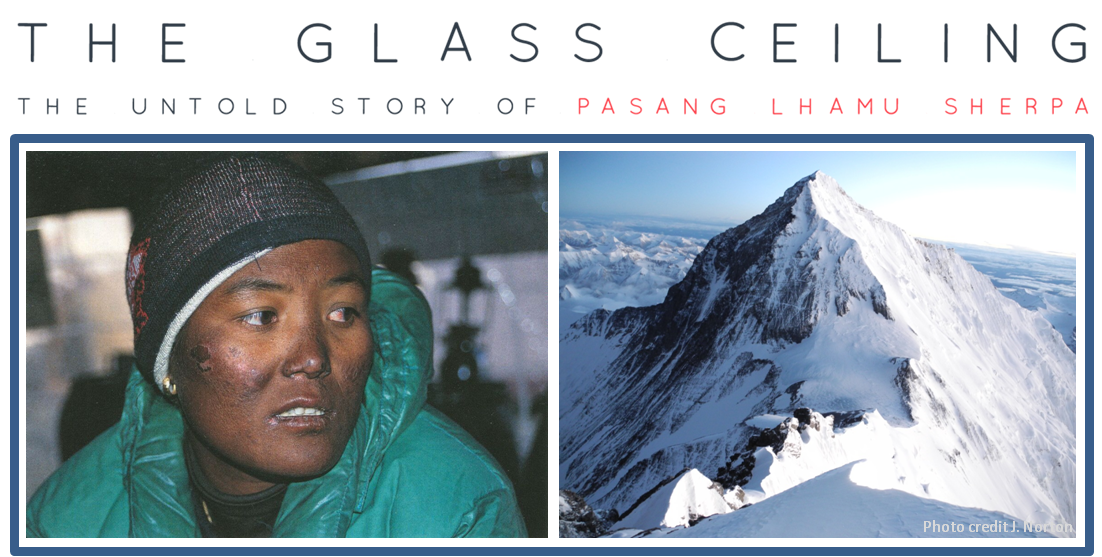

The Glass Ceiling: The incredible story of a Nepali woman who climbed Mount Everest and inspired her nation

Documentary tells story of Pasang Lhamu Sherpa who perished on the descent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ten years ago, at a summer cabin in Lake Tahoe, Nancy Svendsen was told a story she could scarcely believe.

The story recounted by her brother-in-law, who had moved to the US from Kathmandu three decades ago, was about Pasang Lhamu Sherpa, who was raised in poverty amid a patriarchal culture, and who yet, on 22 April 1993, became the first Nepali woman to reach the summit of Mount Everest.

In doing so, Pasang Lhamu Sherpa inspired many thousands of young women across Nepal and beyond, even though she died on the descent, aged just 32. She was Svendsen’s brother-in-law’s only sister.

Now, the story of Pasang Lhamu Sherpa and the influence she had on so many people, especially young Nepali women, is set to be told in a forthcoming documentary, The Glass Ceiling, directed by Svendsen and with Alison Levine, an American climber who herself reached the summit of Everest and who led the first US Women’s Everest Expedition in 2002, serving as executive producer.

“She became a hero of the people with what she did,” said Svendsen, speaking from California. “It was her fourth attempt and it was the first Nepali-sponsored expedition. Everyone was following her.”

She added: “Countless Nepali women told me she was an inspiration to them. People are very proud of her.”

Pasang Lhamu Sherpa was born in 1961 in Surke, a small town in central Nepal One of six children, she was born into a family of sherpas – a northeastern Nepali community renowned for its mountaineering skills – and wanted to follow in the tradition of climbing and guiding.

From the start, she faced stiff opposition from her family who instead sought arrangement for her to be married – something she ran away from. Eventually, she fell in love with and married another sherpa, and the couple had three children.

“That was the most important thing to her – climbing,” said Dorjee Sherpa, Svendsen’s brother-in-law and the brother of Pasang Lhamu Sherpa. “There were no women in the industry at that time. Not even in trekking.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Nepal, a landlocked nation of 29 million people tucked in the Himalayas between India and Tibet, only began opening itself to foreign visitors in the 1950s.

For more than 200 years it was ruled by an absolute monarchy, and parliamentary elections were first established in 1990. After a decade of civil war between Maoist insurgents and government troops, a peace deal was signed in 2006. Part of that deal involved the scrapping of the monarchy and the country’s transformation into a republic.

Today, with both India and China competing for influence in the Hindu-majority nation, GDP stands at less than around $2,000 per person. Tourism only accounts for three per cent of the national GDP, yet it is the second-biggest foreign income earner after remittances.

Many of those tourists are people who visit to climb or trek, an industry at which the sherpas, an ethnic group long associated with their ability to work and climb at altitude, play a central role.

Yet the sherpas have had a love-hate relationship with the industry and with the foreign climbers whose money is crucial to many local economies. The sherpas complain that while the foreign guests they guide are heavily insured and receive rapid emergency help in the case of accidents, they do not.

The deaths of 16 sherpas in a 2014 avalanche, and the miserly compensation paid to the victims’ families by the Nepali government, led them to collectively refuse to work for the rest of the climbing season.

It was against such a backdrop that Pasang Lhamu Sherpa grew up, determined to do what her male family members were doing. Levine said she understood some of the pressure and discrimination faced by women climbers, even in the West, and especially those who have children.

“Men are considered heroic [for climbing] while women are called irresponsible,” she said.

The documentary makers have completed filming and have launched an Indiegogo campaign to help meet the costs of post-production, which include commissioning an original musical score, colour correction and sound effects.

Levine said she was amazed the story of Pasang Lhamu Sherpa, who has had stamps, a mountain pass and even a strain of wheat named in her honour, is not better known outside of Nepal.

“One woman’s courage changed an entire country,” she said. “That is an amazing message.”

Dorjee Sherpa, Pasang Lhamu Sherpa’s brother and the man who told Svendsen the incredible story on the summer trip to Lake Tahoe, said he had last seen his sister in 1992, a year before that fourth attempt on the world’s highest mountain which cost her her life.

He said he had cautioned her about the climb, warning of the dangers. “She said it was important to share our experiences with the younger generation of sherpas. There were no women involved and she said ‘if I can climb Everest – if I can complete my dream – young women can do it too’. That was one of the last serious conversations we had.”

If his sister, whose funeral in Kathmandu’s Dasarath Rangasala soccer stadium was attended by thousands, were still alive, he said she would be heavily involved in publicising and promoting the film.

He said: “She had already had such a big impact. Since she climbed Everest, others have completed it. She helped those other women do it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments