Marisa Berenson on the making of Barry Lyndon: Kubrick wasn't a 'difficult ogre - he was a perfectionist'

The actor recalls working with the famously reclusive director on the 1975 movie

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Interviewed in the bar of an upmarket Piccadilly hotel, Marisa Berenson, now 69, cuts the same elegant figure she did when playing Lady Lyndon in Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 period drama movie Barry Lyndon. She is in London over the summer, appearing as Lady Capulet in the Kenneth Branagh Theatre Company production of Romeo And Juliet. Her account of the making of Barry Lyndon reveals that familiar mix of affection, awe and exasperation that so many of Kubrick’s collaborators felt about working with him. It’s a fascinating, comical and very embroiled story, involving everyone from Peter Sellers to the IRA.

“He [Kubrick] just called me up one day,” Berenson recalls. The director had been given her number by a mutual friend, Stanley Donen (director of Singin’ In The Rain). He thought that Berenson was German because of her accent in Cabaret. “Oh, no,” Donen had told him. “I’ve known her since she was a little girl. She’s not at all German. She speaks perfect English.”

Berenson was intrigued to receive the phone call from Kubrick. She had no idea what he looked like. (The American director was reclusive and rarely photographed.) “When he called, I was sick in bed with pneumonia,” she says. “I had this very high fever. I didn’t say much. He just told me wanted me to play this English countess in a film of a Thackeray novel.”

Berenson didn’t actually meet her director until six months later. In the intervening period, she had read the Thackeray novel and had been struck by the fact that Lady Lyndon didn’t feature especially prominently. Not that she had second thoughts about taking the role. As she puts it, “when a great director says to you ‘I want you to do a part’, you just say yes. You know that it is going to have his vision and that it will be extraordinary one way or the other.”

Eventually, Berenson went to visit Kubrick at his home outside London. She had her costume fittings and tried on her wigs. Kubrick complimented her on the way she did her make-up but, otherwise, gave her few instructions about how she should play the role.

“I liked him [Kubrick] very much. He had a lot of dry humour. Contrary to what people think – they have this image of Stanley as this difficult ogre – he wasn’t at all. He was a perfectionist but every great director I’ve worked with has been a perfectionist. You have to be to make extraordinary films.”

Kubrick, she adds, was “a very cosy man”, who loved his kids, his dogs and his garden. He played the piano. He liked to dance. He adored his wife. It was just than when it came to movies, he was obsessive, “bulimic for information,” as she puts it, “wanting to know everything about everything". He was also determinedly eccentric, driving very slowly, wearing a helmet in his bullet proof car and only leaving his home counties base when there was no other choice.

With extreme reluctance, to save money, Kubrick had agreed to make Barry Lyndon in Ireland.

For the first three months of shooting, Berenson didn’t appear in a single scene. She was on call all the time but wasn’t used once. The rain was incessant. “I tell you, I didn’t do one day of shooting in Ireland and I was there for three months,” the actress exclaims.

Her friend Peter Sellers arranged for her to live in the wing of an old Irish castle “to get in the mood of the character". The place was run down with bad electricity and no heating. Berenson was living there on her own, trying to keep herself calm by meditating and doing yoga even as she shivered. She asked Kubrick if she could go home for Christmas. “No,” came the reply. “I might need you tomorrow.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Eventually, Kubrick closed down the production and left for London in the middle of the night. No one knew why, although the speculation was that there had been threats from the IRA. The director planned to start shooting again in England. It was a decision that drove his production designer Ken Adam to a nervous breakdown.

“Poor Ken had to go through the whole process of all the castles, the permissions, the sets ... it was a very complicated movie to do, and he had spend a year doing that in Ireland already.”

As a highly paid model, Berenson was accustomed to complicated photo shoots but nothing had prepared her for Kubrick’s way or working – in particular, his decision to use thousands of candles to light the film rather than electricity. (This was one of his ways of ensuring period authenticity.)

“The lighting was so beautiful in that film. You can tell when you’re being lit if the lighting is good or not. We were shooting in these big, cold castles with candles burning - so they had to be changed. He was shooting with this very sensitive lens that shot in the dark. NASA had the other one. I couldn’t really move very much because otherwise you would go out of focus. It was very constricting but for for my part, Lady Lyndon was a repressed woman anyway, it was perfect.”

Kubrick shot multiple takes of every scene – a source of some discomfort for Berenson in a famous scene in which she is shown in a bath with her courtiers around her. Inevitably, the water grew cold. Kubrick allowed it to be replaced with hot water but insisted its level stayed exactly the same.

The film was supposed to take six months to shoot but ended up taking over a year. “I just went into a bubble,” Berenson recalls. “I didn’t see the light. I didn’t see anything or anyone until I had finished the movie.”

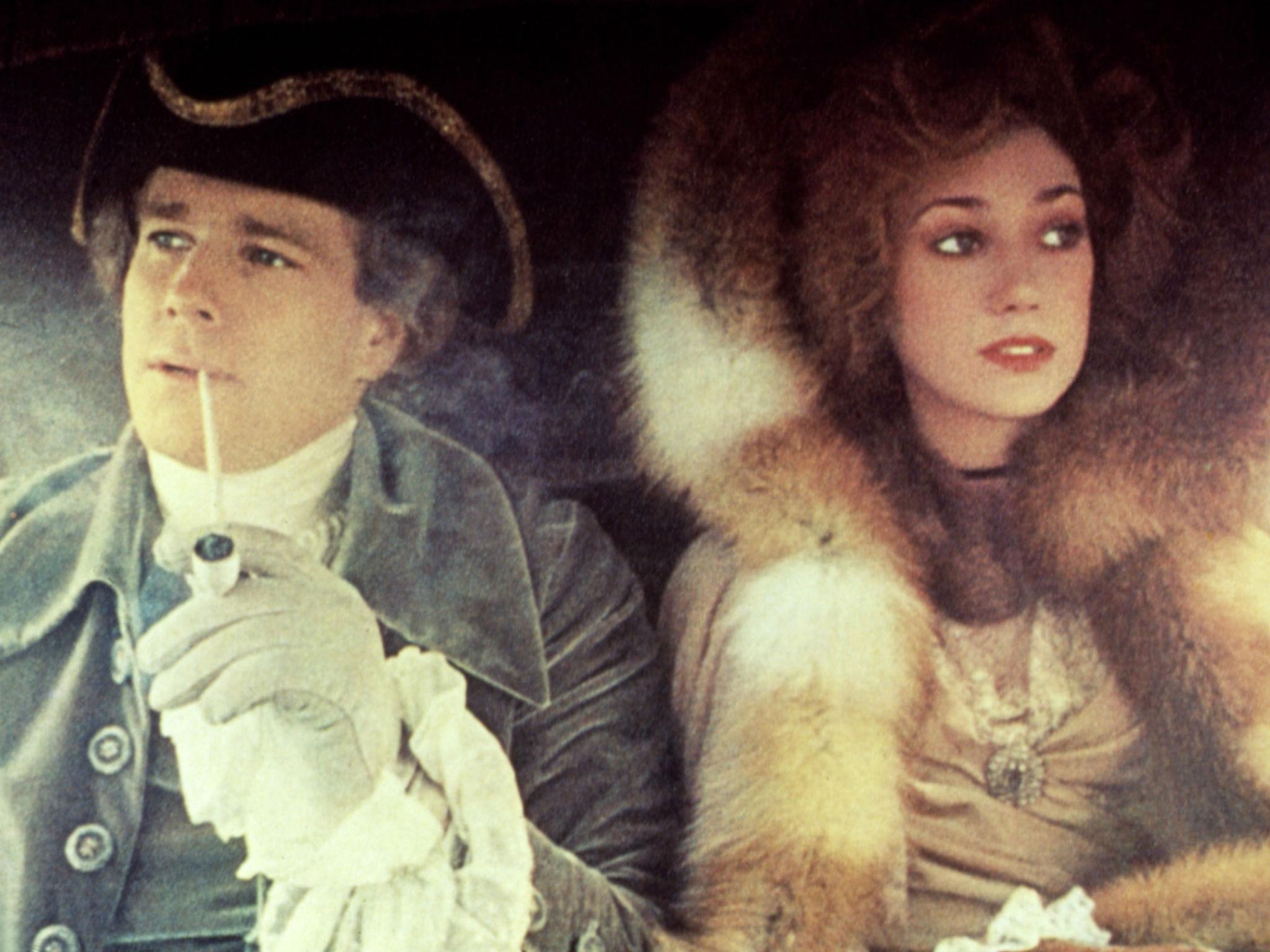

Her relationship with her co-star Ryan O’Neal (who plays Redmond Barry, the Irish chancer who married Lady Lyndon for her wealth) seems to have been ambivalent. “He was OK,” she says guardedly of the hell-raising actor but acknowledges that, like Kubrick, O’Neal had a good sense of humour. “He would always crack jokes and try to make me laugh in the scenes when I had to be crying and dramatic which I was always upset about.”

True to his reputation, Kubrick was very secretive about the shooting of the movie. When he finally allowed senior Warner Bros executives to see 20 minutes of the material, he insisted on them spending four days in a hotel. “They weren’t allowed to do anything. He didn’t want them jet-lagged, he didn’t want them tired.”

When shooting was finally completed, O’Neal annoyed Kubrick by making critical remarks about the movie in the press. (He may have been jealous that Berenson, not him, had appeared on the cover of Time magazine, billed as Kubrick’s latest muse in the director’s “grandest gamble".) It was therefore left to Berenson to go on a world publicity tour on her own.

On its initial release, Barry Lyndon was respectfully received and was admired for its technical excellence, but it certainly wasn’t loved by the critics. Some felt it was too picturesque, “the motion picture equivalent of one of those very large, very expensive, very elegant and very dull books that exist solely to be seen on coffee tables”, as one wrote. In the intervening years, it has been re-evaluated and is now seen as one of its director’s supreme achievements.

For Berenson, for better or worse, the film continues to define her career. “This film, there is not a day that goes by without someone talking about it. It is really the film that has marked me the most. Everybody associates me with Barry Lyndon.”

Kubrick made huge demands on his leading actress but, once she finally came up for air, the rewards for her were obvious. “Getting back into the world after Barry Lyndon was a strange thing,” she reflects. “I was cut off from everything for such a long time. Stanley would sometimes see me becoming a bit melancholy because I hadn’t gone home and he would say, ‘you have no idea what this film is going to do for you’.”

‘Barry Lyndon’ is re-released in a restored version on 29 July. It coincides with Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick in partnership with Canon, an original exhibition at Somerset House, London, running until 29 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments