Jo Nesbo and Nordic noir: Evil in the land of the midnight sun

Concluding his three-part odyssey into the heart of Nordic noir, Andy Martin travels to Oslo to meet master of the genre and self-confessed ‘perverted soul’ Jo Nesbo, and asks whether Scandi-bleakness simply reflects inherent human depravity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Jo Nesbo was 13, his class at school on the west coast of Norway was set a typical creative writing task, “A Walk in the Woods”. The other kids wrote about picnics and climbing trees and bird-watching. Nice. The story the young Jo submitted was relatively untypical. Not nice at all. “Basically, nobody came back,” he says. Everybody died, one way or another. Axe, knife, gun, rope, whatever. Lord of the Flies but with more Christmas trees and, as per the title of one of his most recent thrillers, blood on snow. So many ways to die in Norway. It’s like the line of least resistance. All it takes is a little shove. “My teacher was worried about me,” he recalls. “She wrote a letter home. So my mother was worried too. I started to realise I was a very strange person. A perverted soul. That’s the good thing about getting older: you realise that it’s normal to be abnormal.”

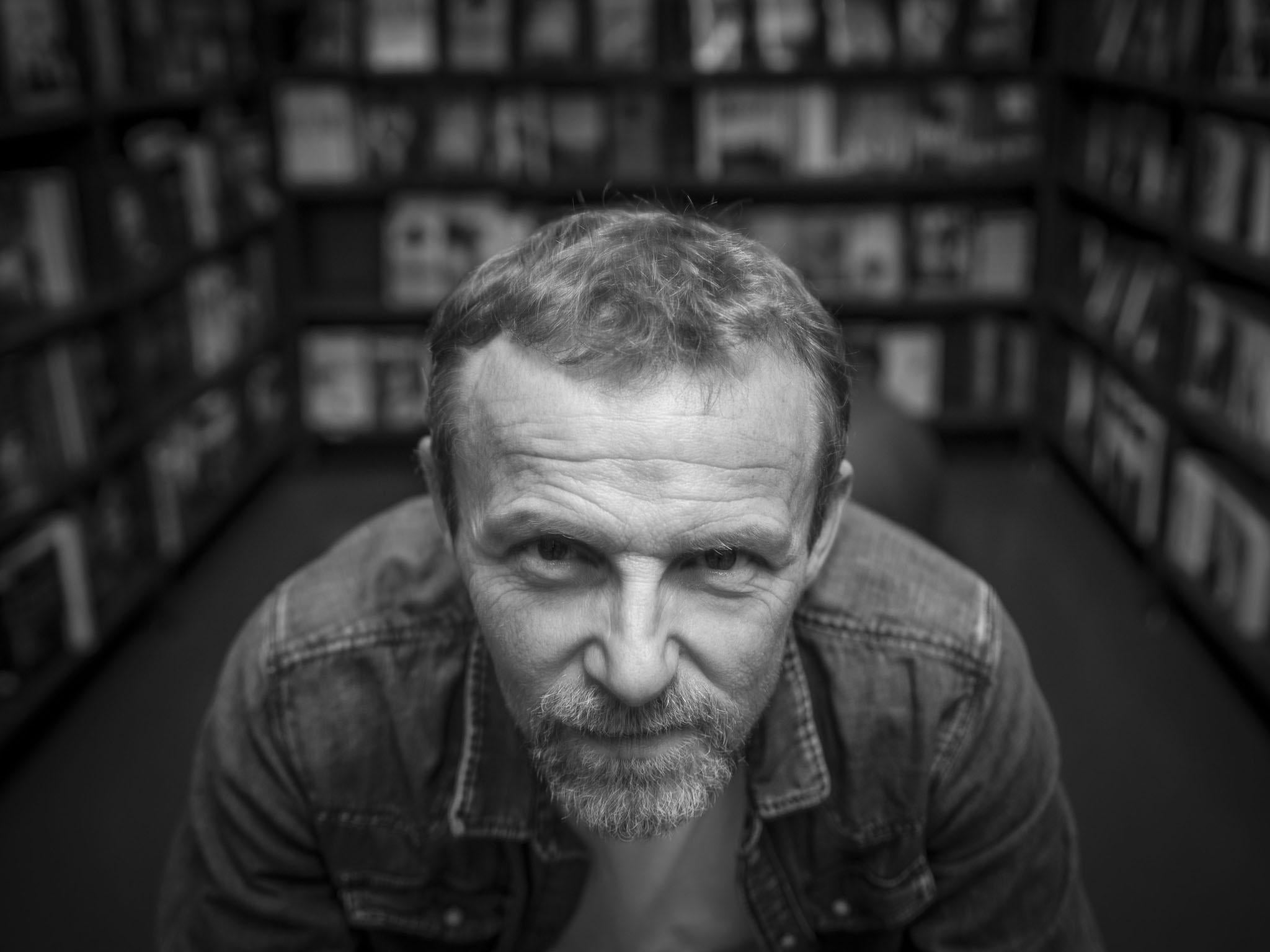

Nesbo, apart from being Norway’s biggest bestselling writer and translated into 50-odd languages, has been a footballer (he played for Molde FK till an injury finished his career aged 19), a stockbroker, and a rock star. He is a rugged mountaineer and is wearing a dark climber’s sweater emblazoned with the outline and names of peaks around the fjord of Molde. But the line that springs to mind as we sit together in Bolgen & Moi Briskeby brasserie (groovy industrial chic with nice lamps) in Oslo this dark night, snacking on olives, is that refrain from Monty Python’s Life of Brian: he’s not the messiah, he’s just a very naughty boy.

He is sinewy like a long-distance runner and has scruffy hair and a scruffy

beard and a mischievous look. A blonde Norwegian Bob Dylan, but younger. Softly spoken. There is a Freudian undertow in all Nesbo novels, exemplified by the flashback, where someone about to do something extremely atrocious (consider The Snowman, for example) is taken back in time to the infantile trauma that triggered or goes some way towards explaining his or her current bad behaviour. The Snowman’s defence would be Philip Larkin’s: “they f*** you up, your mum and dad. They may not mean to but they do.”

Now The Snowman has been made into a movie, starring Michael Fassbender and directed by Tomas Alfredson, who helmed Let the Right One In and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. It probably won’t replace Raymond Briggs as Christmas family viewing. And you may never be able to build a snowman again with quite the same innocent enthusiasm. But if you watch very carefully, you may spot Nesbo, seen from behind, holding a dog.

In his case, it was more: they tuck you up and read you stories. His father was Norwegian but grew up in Brooklyn, New York, in the Bay Ridge area near the shipyards. When the young Jo was growing up in Oslo and on the west coast his father spun him tales that made Brooklyn sound like pure Godfather, a criminal underworld populated by enchanting monsters and maniacs. “There was a mysterious pool player who always wore a hood. And the menfolk would be away from home for long periods, but when they came back they would always bring expensive presents.”

Some years ago Nesbo made a pilgrimage to the Brooklyn house his grandparents once owned and he brought the American hardboiled gangster Scorsese/Raymond Chandler/Dashiell Hammett tradition back home to Norway. Harry Hole is his very tall, flawed, alcoholic Philip Marlowe/Sam Spade detective, the recurring hero of 10 novels, and due to appear in an 11th, The Thirst, due out here next May. “It’s a very strange job, what I do,” Nesbo says. “You’re lying in bed in the morning, still half-asleep, and you come up with a crazy way to kill someone. Then you get up a happy man and get right down to work.”

Readers of The Leopard will recall the fiendish “Leopold’s Apple”, that does for quite a few poor victims and causes his loner detective to commit yet more self-harm and go some way towards justifying the English pronunciation of his name (I can’t say more). It was based on something the young Jo really got up to when he was dared by his brother to try and swallow an entire apple while it was still hanging on the tree at their grandma’s house – and he wondered if his head might explode. In retrospect Nesbo is actually a little bit apologetic about this book and feels that some of its brutality was “unnecessary to the story”. The naughty boy is sorry for being quite so naughty. He likes to “take away what is not needed”.

But he recalls another scene more fondly. Back in the Nineties, when he was suffering from a bad back, his doctor persuaded him to buy a waterbed. “I didn’t like it much. It made these odd gurgling noises. And then at a certain point I realised that intelligent life was developing in my waterbed. Not very intelligent – bacteria – but they were in there while I was lying on top of it. Which gave me an idea…”

It’s a one-night stand. A man and a woman meet in a bar. She goes back to his place. They have sex, on a waterbed. There is a certain amount of gurgling, but nothing too unpleasant. The guy goes off to have a shower. She can hear the shower running. She turns over in bed and makes the disturbing discovery that she is not alone. There is someone else inside the bed. The body of another young woman, preserved not in water but in alcohol, like a Damien Hirst shark. She can just about make out the outlines of the body through the mattress. Then she hears the shower stop… (See The Devil’s Star for more, if you dare.)

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“The great thing about the scene,” says Nesbo, “is that the reader can already work out so much without me having to say it all. If you have someone in a waterbed, it’s someone you want to keep close to you. All the time. Even though dead.” The scene looks back to something that must have already happened in the past, but ahead to something else that could happen in the future, in the case of the woman who is lying there on the bed, the very near future, now the shower has stopped. “When you come up with that scene, you realise that you don’t need to tell the whole story, the reader finds the story inside the scene.” Almost like a body in a waterbed.

The recent Blood on Snow, which I happen to be reading while I am in Oslo, is a short standalone, written in the first-person, about a hitman “fixer” and unreliable narrator who keeps on tailoring the facts to suit himself. It is also a meta-novel about the author. As Albert Camus, another involuntarily retired footballer, argued, fiction rectifies reality in accordance with a metaphysics. It just so happens that the Nesbo metaphysics are a little more murderous than most.

But like any self-respecting criminal mastermind, he doesn’t do anything without a plan. “I work better if I have a plan. I don’t have to stick to the plan.” Before ever writing Chapter one, he will write synopsis after synopsis, for up to a year, ironing out all the wrinkles, developing not just plot and peripeteia (or twists) but character. “Then I am ready. It is already perfect. My job is just to not f*** it up.” His command of English vernacular is impressive.

There are two slightly conflicting strands to Nesbo, which create the essential tension of his books. On the one hand he is highly unrepressed, anarchic, anything-goes. “I never put any censorship on my brain.” On the other, he is focused and calculated and precise to the point of mathematical. “I am the captain of my ship,” he says. “I think it’s reassuring for the readers if the captain knows where he is going.” On this particular evening, the captain is steaming off on a date. Nesbo is unmarried and, according to legend, in high demand. I think he has got rid of the waterbed.

The next day is one of those perfect, crisp sunny days in Oslo. All its gorgeous architecture sharply etched against a pale blue sky. A great-to-be-alive kind of day. On my odyssey around the Nordic noir underworld, I’ve met so many life-enhancing people, like The Killing’s Soren Sveistrup and Sofie Gråbol in Copenhagen, and Sofia Helin and Hans Rosenfeldt across The Bridge in Malmo. Part of their appeal is that they never let you forget the nothingness at the heart of being, the irreducible fact that, in a long-term way, we are all toast. Dust to dust. As in the existential-crisis scene at the end of the third series of The Bridge, we are all standing on the tracks and the express from Stockholm is bearing down on us. Every last one of us, the Nesbo novels remind us, is dangling over an abyss. Or crevasse. And there’s a guy right behind you shoving an electric cattle prod up your arse.

A similarly post-romantic anti-Wordsworthian note is struck in Danish number one Sara Blaedel’s Louise Rick series: don’t go down to the woods. Please. Hence her latest, The Killing Forest. Or, in Norwegian Agnes Ravatn’s recent The Bird Tribunal: don’t row row row your boat you fool, not with that guy! Perhaps the theme of Death in a Cold Climate – the title of Barry Forshaw’s encyclopaedic book on Nordic noir – has an almost nostalgic appeal in the age of global warming.

I am heading to the Litteraturhuset (“House of Literature”, funded by the Freedom of Expression Foundation), tucked behind the Royal Palace. Oslo’s noir factory. It’s like a library, but they are actually writing the books right there. The inner sanctum, up in the loft, is the Skribentarbeidsplasser (“Writerworkplace”) where a dozen or more writers, men and women, are quietly tapping at keyboards, conjuring up new horrors, murder and massacre on an industrial scale, vast infernal conspiracies. I could only hope that there would be a Harry Hole or a Saga Noren or a Sarah Lund to restore the cosmic balance. None of them, I am tempted to say, were making anything up. It is impossible to imagine anything worse than what actual human beings do to one another. Nordic noir is merely a fresh iteration of an immemorial murderous tradition.

One of the Litteraturhuset regulars was Ben McPherson, a tall, grizzled Scottish writer, author of A Line of Blood, who attended the Anders Breivik trial. Breivik holds the record for a lone-wolf massacre, killing a total of 73 people in 2011, most of them teenagers, beginning in Oslo and going on to the nearby island of Utoya. McPherson is now at work on a novel, This is Not America, in which an American family move to Norway in search of a less violent society and then lose their daughter in a massacre. What, as the great French sociologist Emile Durkheim would ask, is the “function” of noir? It is surely, as Sofie Grabol suggested in Copenhagen, to replicate and exorcise “fear and trembling”. But McPherson’s book spells it out very specifically: don’t be deluded, there is no perfect place. Something is rotten in the state of Denmark, Sweden and Norway (and everywhere else).

Breivik himself was in the grip of utopian thinking: the massacre was a measure of his disappointment at Norway’s inability to live up to some imaginary ancient purity that existed only in his head. Nordic noir is not dystopian, but it is anti-utopian. I think there is a clue in the word “noir” itself. The original Swedish title of Larsson’s first novel in the Millennium trilogy, better known as The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, was Men Who Hate Women (Man Som Hatar Kvinnor). The symbolic mission of Lisbeth Salander and Sarah Lund and Saga Noren is, so far as possible, to eradicate the big white guys, the Vikings, who feel they are sexually entitled, driven by an atavistic droit de seigneur. If literature is an alternate religion, then Nordic noir is its most audible prayer. The task of the House of Literature is apotropaic: to offer up human sacrifices, in fictional form, to ward off evil and conjure up the return of the light.

I head back down the hill towards Oslo central station. Outside the Royal Palace two identical sentries, as immaculate as toy soldiers, are marching up and down, symmetrically, with extreme precision, rifles over their shoulders. The sun is setting and darkness is descending over Oslo.

Andy Martin is a lecturer at Cambridge University and is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’ (Bantam Press, RRP £18.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments