Mutant misery: How the X-Men franchise lost its superpowers

It redefined the superhero film with its emotional themes and thoughtful casting, but 20 years since its big screen debut, the X-Men saga has gone from sublime to stinking. Ed Power speaks to its fans and creators about its rise and fall

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It had taken nearly 25 years but finally, in July 2000, a superhero movie came face to face with true human evil. With rain spitting down, a Jewish boy is separated from his parents by guards at Auschwitz. He cries out. The camp gates warp and bend. Channeling his “mutant” powers, the young Magneto begins to rip apart this monument to man’s capacity for cruelty beyond comprehension, barbed wire by barbed wire. As the scene plays out in all its muddy brutality, a great cacophony rushes up. It is the sound of a child with strange gifts lashing out at a world brimming with wickedness. It is also the sound of the comic-book movie growing up in front of your eyes.

Before the first X-Men film, released 20 years ago on 12 July, superhero films came in 50 flavours of juvenile wish-fulfilment. They could be bright and shiny – Christopher Reeve’s 1978 original of the species, Superman, for instance – or adolescent and moody (Tim Burton’s Batman). What they weren’t was particularly mature or thoughtful. They certainly never dared seriously scrutinise the dark side of human nature, the side that led to the death camps. And then along came X-Men to change all that.

X-Men was a “team-up” adventure roughly analogous to Marvel’s Avengers. The setting was a world where genetic mutations have created a new race of super-powered individuals. Some – steel-clawed Wolverine, weather-controlling Storm – used their powers for good. Others, such as the now elderly, embittered Magneto, believed humans an inferior species who should bow down to their new masters. The journey to the multiplex hadn’t been straightforward. Early in the process it appeared X-Men might just be another cautionary tale of a comic-book property failing to translate. The Nineties had been littered with examples, from Spawn to Tank Girl.

“The X-Men movie project started out as a debacle,” says David Mumpower, a writer with Marvelblog.com. “They [20th Century Fox] rejected several potential storyline scripts, including ones by Joss Whedon and Laeta Kalogridis, who later produced Avatar and Altered Carbon. The early perception of this production was that it was doomed.”

X-Men director Bryan Singer realised radical action was required. So he took a huge risk and cut the movie to just 95 minutes, stripping it to the bare essentials. “Singer’s willingness to kill his darlings led to a kind of superhero movie nobody had seen before,” says Mumpower. “It was all action scenes and character-focused. Plus, X-Men featured a superhero team-up, a rarity for comic-book films at the time. Even better, some of the characters didn’t really like one another [ie the feud between Wolverine and Cyclops]. That was new… the freshness of X-Men elevated it.”

With Patrick Stewart’s Professor Charles Francis Xavier and Ian McKellen’s Magneto at the head of two warring clans of overpowered “mutants”, Singer’s tour de force heralded a brave new dawn for super-hero cinema. Or so it appeared at the time. X-Men was astute and sophisticated in its portrayal of a world where superpowers are real. Politicians called for these “mutants” to be publicly identified and if necessary imprisoned. Ordinary people saw them as freaks to be shunned. Compared to Superman and Batman, this was nuanced stuff. It represented a game-changer for a genre still widely scorned as an escape hatch for the socially awkward and terminally pungent. Yet the bright future that beckoned never quite came to pass. Not for X-Men at least. Two decades later, the franchise stands as the ultimate cinematic hodgepodge. There are some outstanding X-Men movies – most notably James Mangold’s 2017 revisionist masterpiece Logan. However, there are also many many spandex-wrapped duds among the 10 entries in the series. The most notorious example is perhaps last year’s X-Men: Dark Phoenix. Starring Sophie Turner in the honeymoon period of her post-Game of Thrones stardom, the film was a $100m bomb and a public humiliation for everyone involved. How did X-Men go from sublime to stinking, even as the rival Marvel Cinematic Universe, cobbling together such obscure and cartoonish characters as Iron Man and Thor, conquered the box office?

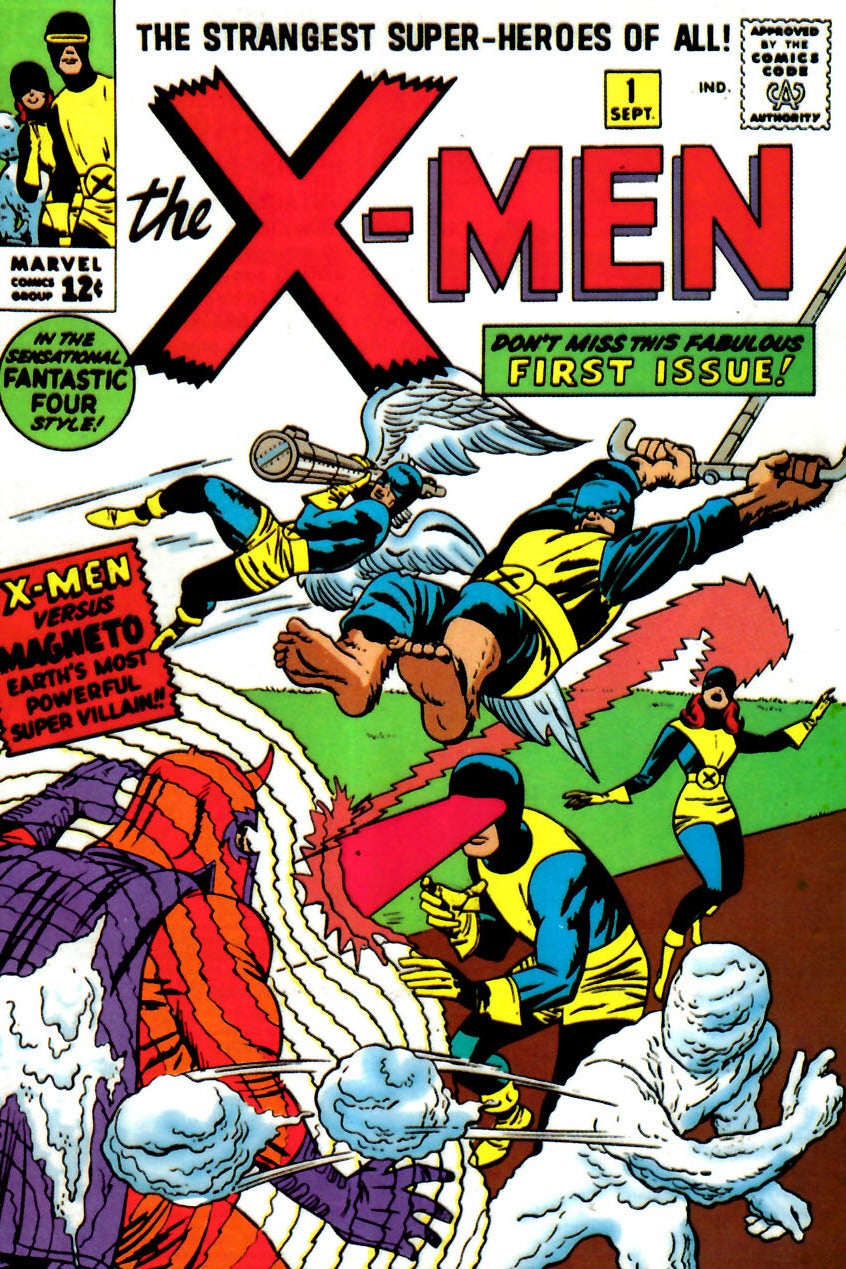

To answer that question it is necessary to travel back to 1963, when Marvel’s Stan Lee, working with his regular artist collaborator Jack Kirby, created a new saga of crime-fighting “mutants”. They did so in the face of considerable internal resistance at Marvel. The concept of a society of freaks and outcasts saving the world struck some at Marvel as going too far – even from the writer who had given the world Ant-Man and Dr Strange.

There was pushback throughout the process. “In the beginning I was going to call them mutants,” Lee would tell a 20th Century Fox documentary accompanying the release of X2 in 2003. “But the publisher didn’t like the name. ‘Stan, nobody is going to know what mutants are…’. To this day I can’t understand why he felt if people won’t know what mutants are…they would know what an X-Man is.

X-Men aspired to be something more than another biff-pow fest. Lee’s mutants were a misunderstood minority. They had pledged to protect civilisation. But unlike Spider-Man, Iron Man and friends, they never got their due. The more they risked themselves, the greater the suspicion in which they were held by the public. They were the eternal outsiders, the quintessential underdogs. “[There was] an element of the McCarthy era,” said Chris Claremont, who inherited X-Men from Lee in the Seventies, in 2003’s The Secret Origin of X-Men. “The key to the X-Men from the start had been that they were feared and hated by the world they had sworn to protect.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Because of disappointing sales, X-Men had been shelved by the time Claremont joined Marvel. He begged his boss, Len Wein, to let him write the revived series. Upon receiving the green light in 1975 he set about distinguishing the Uncanny X-Men – as the new run was titled – from other superhero team-ups. What would be the point of a poor-man’s Fantastic Four or Avengers?

“The idea of having strong dynamic women characters in the comic medium was rare…the idea of having a major black character was very rare. Women then were basically defined as girlfriends,” said Claremont. “Very rarely did you find one that was capable of holding the centre of a book all by themselves. It struck a real chord.” He was talking about the aforementioned Storm, the weather-controlling mutant portrayed in the early Singer movies by Halle Berry. Joining her in the rebooted comics was another new character: a grumpy grizzly gentleman with retractable steel claws. “One of the things people like about [Wolverine] was…he’s not a goodie goodie,” said Lee. “This guy is rough and bad tempered. Underneath it all he has a good heart.”

The Wolverine/Logan part in the films was originally offered to Russell Crowe. He demurred but suggested 20th Century Fox consider a friend of his, an unknown fellow Antipodean with a background in musical theatre named Hugh Jackman. Jackman was one of more than a dozen potential Wolverines considered by director Bryan Singer, who had himself required a great deal of persuasion to become involved with X-Men in the first place. His 1995 neo-noir masterpiece The Usual Suspects had made him a sensation around Hollywood. And despite the failure of 1998’s Apt Pupil, 20th Century Fox had lobbied hard for him to take on X-Men. Singer, though, wasn’t a “comic-book guy”. Did he really want to squander the clout he had worked so hard to accumulate on a project that might well prove to be a disaster on the scale of Joel Schumacher’s Batman & Robin?

“I never really read comics as a kid,” he said later. “But I was a great fan of science fiction and fantasy literature and movies. And when [the movie] was presented to me…I started to examine the material and look at the characters’ histories. This was Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s way of commenting on prejudice.”

Singer would go on to direct four X-Men movies – including 2003’s acclaimed X2. But his career would stall in 2018 amid rumours about his personal life; last year, for instance, it was revealed that he settled a 2003 rape allegation by a then 17-year-old boy out of court for $150,000 (£118,000), though he maintained his innocence.

A cloud would similarly come to hang over Brett Ratner, director of 2006’s X-Men: The Last Stand, the panned third outing in the series. In November 2017, seven actresses, among them Olivia Munn and Natasha Henstridge, accused Ratner of harassment and sexual assault. Warner Bros later cut its links with him. Ellen Page subsequently claimed that Ratner had belittled her on the set of The Last Stand by suggesting she sleep with a fellow female cast member to out herself as gay.

“I was a young adult who had not yet come out to myself.” she wrote on Facebook. “I knew I was gay, but did not know, so to speak. I felt violated when this happened. I looked down at my feet, didn’t say a word and watched as no one else did either.”

Did allegations about Ratner and Singer cast a toxic shadow over the franchise? Obviously yes – but the films were in any event perfectly capable of mucking up on their own. The Last Stand, for instance, was a noisy, soulless mess, lacking even decent action scenes. And Dark Phoenix – which reprised the same storyline in which the telepathic Jean Grey goes bad – was even more of a muddle. True, the series briefly got back on track in 2011 with Matthew Vaughn’s “before they were infamous” flashback movie, X-Men: First Class. It took risks in casting Michael Fassbender and James McAvoy as the young Magneto and Professor X and using the Sixties milieu of Cold War espionage as the backdrop.

Alas, that good work was quickly undone. Singer was back to direct Fassbender, McAvoy and the up-and-comer Jennifer Lawrence as the rebooted shapeshifter Mystique in 2014’s X-Men: Days of Future Past. Through time-travel chicanery it paired the youthful Magneto and McAvoy with present-day Wolverine and genuine chemistry was sparked. But Singer’s directing was broad and unimaginative; the film lumbered when it should have soared. Next, Singer somehow persuaded Academy Award-nominee Oscar Isaac to portray intergalactic Blue Meanie Apocalypse in the creaking X-Men: Apocalypse from 2016.

Apocalypse went out if its way, it appeared, to undo much of the good work of the early X-Men. There was criticism, in particular, of a set-piece in which Magneto and Apocalypse team up to thrash Auschwitz in a cartoonish style that turns the concentration camp into a wobbly disintegrating computer animation. Compared to the taut sequence from the original movie, this was crass and clumsy – with Auschwitz reduced to a fountain of iffy CGI twirling ludicrously about Fassbender’s Magneto like a video-game cutscene.

“A shocking and deeply uncomfortable moment, even though the destruction was all digital,” said science and nerd culture website Inverse. “Detonating a place where some of the worst atrocities of the 20th century took place, in a comic-book movie no less, feels wildly unnecessary.” In an era when quippy and quick-paced Marvel films were setting the standard, X-Men had become laboured and uninspired. By the time producer Simon Kinberg stepped in to direct Dark Phoenix, it was clear that the tentpole was about to come crashing to Earth. “If I were to pinpoint a time when they went off the rails, though, I would choose the hiring of Brett Ratner [for Last Stand],” says Mumpower. “He’s all about excess in movies and his personal life. The project needed a more measured approach. Matthew Vaughn brought that to First Class, which is excellent.

“Then, the series returned to Singer, who had already proven that he had lost his fastball, at least in comic-book movies. His next two outings were predictably over the top and unfocused. So, it’s all about hiring the right director, something that has been the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s special skill.”

The only bright points amid all this dross were the X-Men adjacent Deadpool films – set in the same universe though tonally very different – and Logan, James Mangold’s gritty take on the saga. In the latter, Jackman, who’d previously scowled his way through two terrible spin-offs, was on his game playing Wolverine as a cynical gunslinger at the end of the line. It was Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven with extendable metal alloy talons. Smeared in the grime and cynicism of the real world, it was as smart and ambitious a superhero movie as it is possible to imagine a Hollywood studio making. It was also a final hurrah for the dream of what the X-Men could have been.

With Fox absorbed by Disney in a $52bn takeover, it seems clear that the X-Men as we knew them are over (though a much-delayed New Mutants movie, starring Game of Thrones’ Maisie Williams and focusing on several lesser known characters, may finally see daylight in 2020). Future X-Men projects are likely to be under the banner of Disney’s Marvel empire, with MCU overlord Kevin Feige hinting the X-Men might feature in Marvel’s upcoming “phase five”. Having promised so much, in the end the X-Men lacked a vital cinematic superpower: the ability to leave behind a coherent legacy.

“Disney’s way of making movies is vastly superior to Fox’s, which is an easy notion to support based on track records and overall success rates,” says Mumpower, who is inclined to look on the bright side. “So, putting Kevin Feige in charge of the mutants goes a long way to ensuring that the next movie is on the level of First Class rather than The Last Stand. People chose to go to X-Men movies and enjoy them even when they were messy and inconstant. Imagine how well the franchise will do with competent people in charge of all the productions.”

Can Professor Xavier, Magneto and the gang flourish under Marvel? Only time – and a new slate of movies – will tell. But with the early films in the saga having demonstrated so much potential, fans will hope there is still a possibility of more excellent adventures from the X-Men. The characters deserve it. And, having suffered through Dark Phoenix, so do we.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments