Watchmen at 10: The fascinating story of how the 'unfilmable' comic book series finally made it to the big screen

Where Terry Gilliam, Darren Aronofsky and Paul Greengrass failed, director Zack Snyder succeeded. 10 years from 'Watchmen' premiering in London, Jack Shepherd looks at the series' long journey to cinema

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

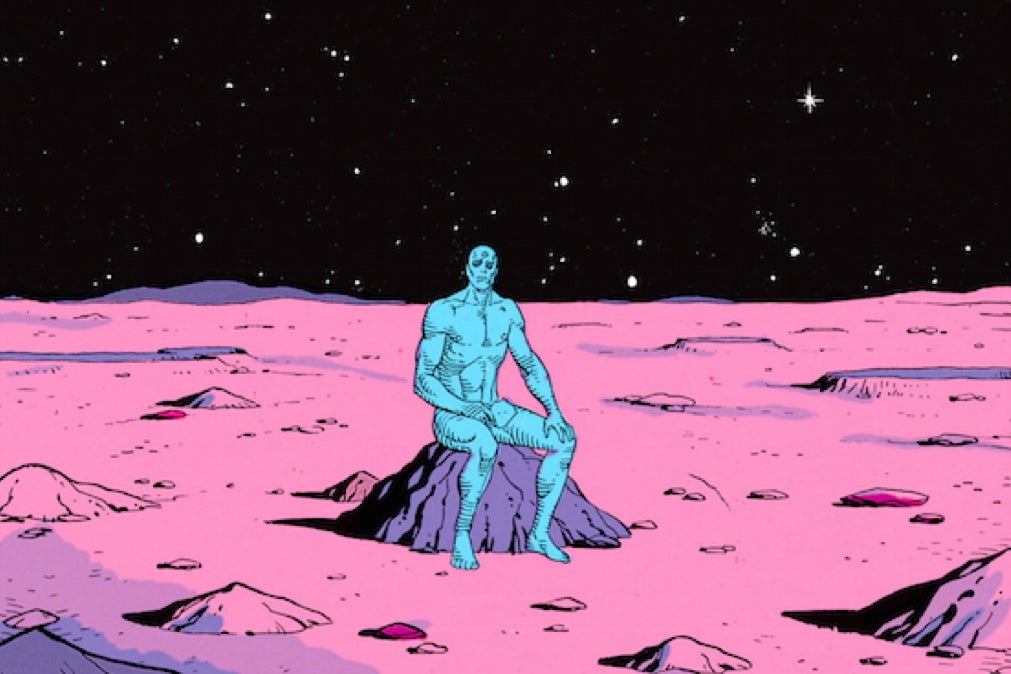

Your support makes all the difference.Chapter four of the graphic novel/comic series Watchmen opens with the omnipotent hero Doctor Manhattan sitting alone on Mars. The colours on the page are remarkable, with the character’s light blue skin and the planet’s purple hues contrasting against the black background of space.

As the chapter progresses, the story shifts turbulently between Mars and Earth, as we learn how the physicist Jon Osterman came to be the God-like Doctor Manhattan. We see the superhero shaking hands with John Kennedy, towering over the Vietcong as a 50-foot giant, and raising a giant glass fortress from Mars’s ground.

The other 11 chapters are equally intense, telling the story of how a band of retired masked vigilantes became tied to the impending nuclear apocalypse. It’s bleak, meta, shockingly violent and has gone down as one of the most influential comic book series of all time.

Perhaps then, it’s no wonder that director Terry Gilliam once called Watchmen “unfilmable”. The story is so grand in scope – social commentary on the Cold War masquerading as a superhero story – and so unanimously viewed as a cultural milestone for storytelling (it remains the only comic book series to win a Hugo Award) that perhaps no one could ever do it justice.

That, of course, did not stop Zack Snyder having a go. In 2009, 10 years ago today (23 February), the filmmaker behind 300 brought Watchmen to the big screen. The story of how the comic book series finally arrived in cinemas is fascinating.

The Eighties were a revolutionary time for comic books. While the medium was still predominantly aimed at children, a wave of gloom-ridden writers brought more adult sensibilities to various publications. Leading the charge was Alan Moore, a budding English writer who broke ground by resuscitating the failing comic The Saga of the Swamp Thing at DC comics.

Moore was critically and commercially acclaimed, thanks to his experimental storytelling and willingness to address real-world topics. Having established himself at DC, Moore pitched his idea to take a set of unused, recognisable characters and revamp them in a dark and twisted tale; one that would inevitably end with multiple deaths.

Unsurprisingly, the managing editor of DC, Dick Giordano, was not best pleased with “their expensive characters ending up either dead or dysfunctional”, as Moore explained, but told the writer to pursue the project with brand new characters.

The result was Watchmen. Written by Moore and drawn by artist Dave Gibbons, the 12-part comic book series was released between 1986 and 1987. It was when they were later published as a single volume graphic novel in 1987 that the critics took the series more seriously. Jay Cocks, writing for Time Magazine in 1988, calling it “a superlative feat of imagination, combining sci-fi, political satire, knowing evocations of comics past and bold re-workings of current graphic formats into a dystopian mystery story”. A Hugo Award soon followed.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Foreseeing that Watchmen would become a huge success, producer Lawrence Gordon scooped up the film rights in 1986. Working with fellow producer Joel Silver, they began developing the project with 20th Century Fox, and the first person they approached to write the screenplay was Moore. He declined the offer.

“With a movie, you are being dragged through the scenario at a relentless 24 frames per second,” Moore later said. “With a comic book, you can dart your eyes back to a previous panel, or you can flip back a couple of pages. Even the best director could not possibly get that amount of information into a few frames of a movie.”

The studio may have failed to gain Moore’s approval, but they persevered, hiring Never Cry Wolf screenwriter Sam Hamm (who would later pen Batman and Batman Returns for Tim Burton). A year later, in 1988, Hamm handed over a first draft, condensing the huge graphic novel into a 128-page screenplay – one that changed the ending and introduced time paradoxes. Come 1991 and Fox dismissed the project and counted their losses, leaving the two producers to look elsewhere.

With the graphic novel having become a phenomenon, picking up a wide-ranging fan-base, Warner Bros jumped on Watchmen. Not only that, but there was an auteur filmmaker coincidently seeking out a new project: Terry Gilliam. The former Monty Python had already directed the experimental films Time Bandits, Brazil and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, and Watchmen seemed a snug fit.

Gilliam immediately wanted to make changes to the screenplay and brought on frequent collaborator Charles McKeown for rewrites. The results were not what Gilliam was looking for, and the director drafted another script with Warren Skaaren, using Hamm’s original as a base. Again, the film’s ending was very different to the graphic novel’s.

“What he did was he told the story as-is,” Silver later said of Gilliam’s script, “but instead of the whole notion of the intergalactic thing, which was too hard and too silly, he maintained that the existence of Doctor Manhattan had changed the whole balance of the world economy, the world political structure”.

Silver explained that Gilliam’s vision for Doctor Manhattan was to have the blue superhero travel back in time to prevent himself from ever accidentally being created. The comic book’s other characters – the masked crime-fighters Rorschach, Nite Owl and Silk Spectre – would end up not being superheroes, but cosplayers walking around Times Square in costume.

“It was very smart, it was very articulate,” Silver continued, “and it really gave a very satisfying resolution to the story, but it just didn’t happen. Lost to time”.

Although the story was very different from the graphic novel, there was one A-Lister wanting to get involved: Arnold Schwarzenegger, who wanted to play Doctor Manhattan. There was also the small matter of budgeting the film. Gilliam’s and Silver’s last projects had both gone way over-budget, and the duo could only find $25m (£19m) to finance Watchmen.

Unfortunately, Gilliam believed they would need at least $100m to make the film. In November 2000, it was reported that the filmmaker had “nailed the coffin closed” on the adaptation. He later called the novel “unfilmable” and that reducing the series into a two-hour film took away “the essence of what Watchmen is about”.

Warner Bros soon dropped the project, and Silver also left as producer. Gordon – who remained on – shopped Watchmen around again, finding a new home at Universal Studios in 2001. David Hayter – coming off the back of scripting X-Men – was hired to write a new script, turning in a first draft a year later (Moore called it “as close as I could imagine anyone getting to Watchmen”). Lloyd Levin (Boogie Nights, Tomb Raider: Lara Croft) then joined as a producer, and Paramount Studios took over the reins from Universal in 2004.

With writer, producers and studio in place, there was one final question: who would direct? Initially, Hollywood’s hottest up-and-coming director, Darren Aronofsky, who had just found success with Requiem for a Dream, came aboard. Aronofsky, though, had something else bubbling in the background – his surrealist film The Fountain. The passion project soon took over, and scheduling conflicts prevented him from working on Watchmen.

Riding high from The Bourne Supremacy, Paul Greengrass joined in November 2004. Hayter’s script remained the foundation and production began in London. Sets were being built, Jude Law and Hilary Swank were both rumoured to have been cast, and a summer 2005 start date was being booked. A teaser website was set up, offering fans a downloadable wallpaper.

Yet, Greengrass’s version was not to be. During this time, Paramount had a reshuffle at the top. It was not until 2006 that the film studio would be split into multiple assets, the regime had changed and, suddenly, the dark tone of Watchmen – alongside the high price tag – was not the direction the studio was headed. Incoming CEO Brad Grey wrote off the whole film, and Gordon was left swearing that he would one day find Watchmen a home.

In December 2005, Watchmen found its final home. Gordon went back to Warner, and they picked up the adaptation once more. They quickly decided to hire Zack Snyder, who had impressed with his adaptation of Frank Miller’s comic book 300. Hayter’s script was still knocking around, and in 2006 Snyder brought in Alex Tse to develop it further.

The following year was spent in pre-production. Snyder decided to use the source material as a storyboard – a technique used on 300 – and negotiated a $100m budget with Warner Bros (although this grew to $120m). The biggest change from the comics was a subplot regarding scarcity of energy resources (an attempt to update the story) and an extension of the fight scenes. Rather than give any meta commentary, akin to what Gilliam had wanted to do, Snyder played the story straight – a decision that would later prove controversial.

Filming began in September 2007 and continued until February 2008. A year later, on 23 February 2009, the film premiered in London. Fans finally had a Watchmen film. The question was – was it the Watchmen they wanted?

“I find film in its modern form to be quite bullying,” said Moore – who has always said he would never watch a filmed adaptation of Watchmen – before Snyder’s release. “It spoon-feeds us, which has the effect of watering down our collective cultural imagination. It is as if we are freshly hatched birds looking up with our mouths open waiting for Hollywood to feed us more regurgitated worms. The Watchmen film sounds like more regurgitated worms. I for one am sick of worms.”

When the “unfilmable” film finally arrived, the conversation turned sour. While some fans raved about Snyder’s stylistic take on the story, others complained that the humour and social commentary of the comic had been stripped away. Some fans believed the director had merely created a straight action film that had none of the subtlety or wit that made comics so ground-breaking.

While there were supporters (the late great Roger Ebert awarded the film a glowing four out of four stars and called it “a compelling visceral film”) the overall consensus was that the film seen in cinemas was a narrative mess. Word of mouth between cinemagoers was weak, and the film fell over 67 per cent at the box office between its first and second weekend.

For what it was worth, Snyder’s “Director’s Cut”, released on DVD, found a new wave of admirers and is generally viewed as superior. Fans of the comic books, though, still have reservations with the film. Critic Douglas Wolk best sums these feelings up: “You can make a movie with the plot of Watchmen, but it won’t be Watchmen. You can kind of imitate it, in the same way you can kind of imitate the way Frank Miller drew the comic book 300. But Watchmen wants to be a comic.”

Snyder later called Watchmen a “labour of love”. “I made it because I knew that the studio would have made the movie anyway and they would have made it crazy,” he said. “So, finally I made it to save it from the Terry Gilliams of this world.”

Gilliam responded somewhat diplomatically: “I always felt it was not the best way to treat it because trying to squeeze it into 2.5 hours is an unlikely thing ... I thought Zack’s film worked well, but it suffered from the very problem that I was happy to avoid by not making the film.”

And yet, despite the muted response to Snyder’s film, despite Gilliam’s warnings, and despite half a dozen other filmmakers trying and failing to make a successful Watchmen adaptation, there’s another one coming. Later this year, Lost co-creator Damon Lindelof’s TV series based on Watchmen will reach HBO. But, unlike Snyder, Lindelof has decided the best way to adapt Watchmen is to not really adapt Watchmen at all.

“We have no desire to ‘adapt’ the 12 issues Mr Moore and Mr Gibbons created 30 years ago,” Lindelof said of the series. “Those issues are sacred ground and they will not be retread nor recreated nor reproduced nor rebooted.”

“They will however be remixed,” he continued. “The bass lines in those familiar tracks are just too good and we’d be fools not to sample them ... This story will be set in the world its creators painstakingly built ... But in the tradition of the work that inspired it, this new story must be original. It has to vibrate with the seismic unpredictability of its own tectonic plates. It must ask new questions and explore the world through a fresh lens.”

Whether Lindelof‘s Watchmen will succeed as a series remains to be seen. Is it right that he remixes the series? Like Doctor Manhattan says during the final Watchmen chapter, “Nothing ever ends” – so perhaps it’s quite fitting.

------

Two of our writers – Jack Shepherd and Jacob Stolworthy – will be analysing Lindelof‘s Watchmen on a weekly podcast when the series begins later this year. Follow along here for all the latest updates.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments