Twiggy on her friendship with Noël Coward and a new season of his films

It started with a brief encounter over tea between the Sixties supermodel and the grand old man of the theatre

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

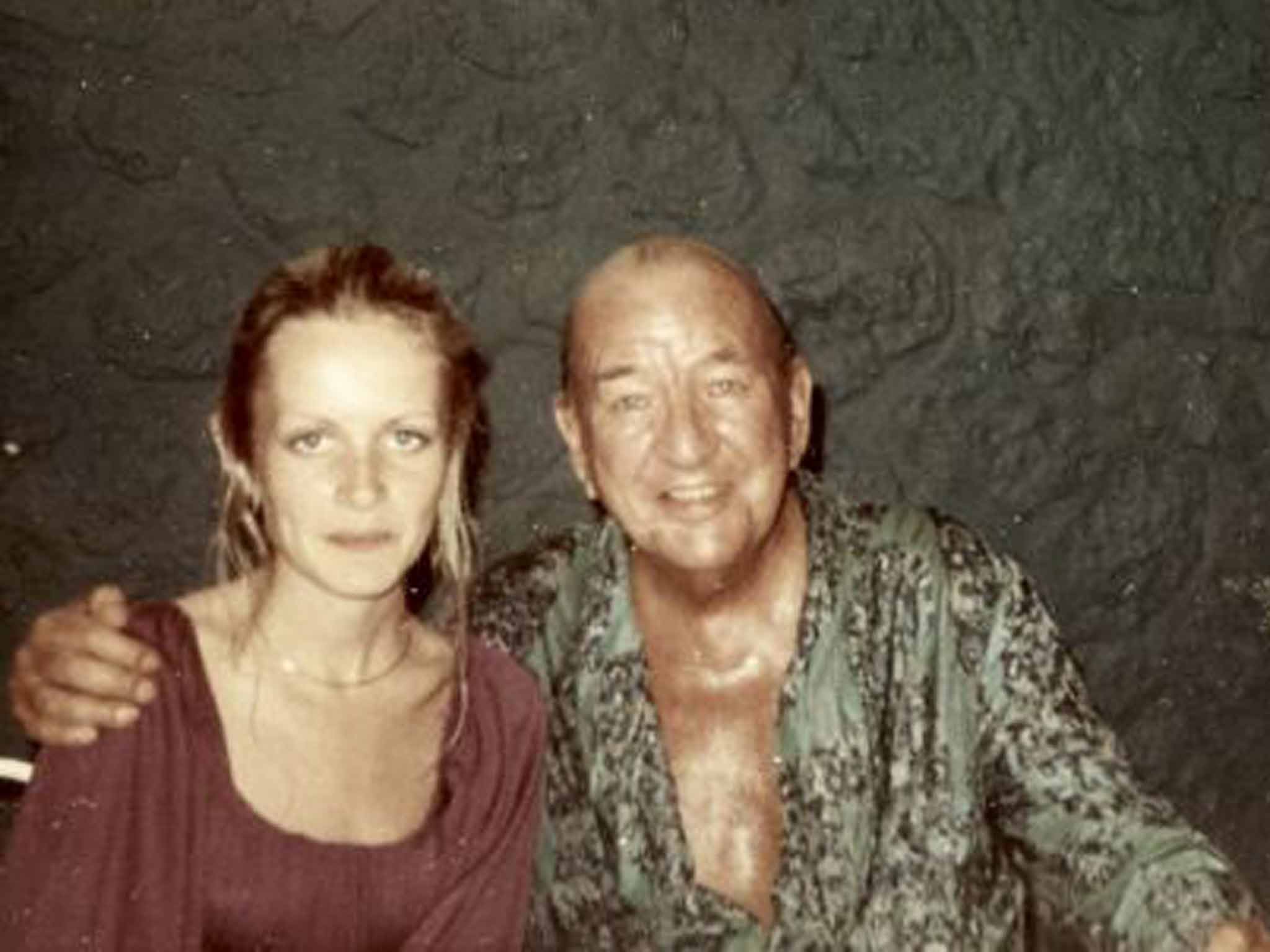

Your support makes all the difference.They make an unlikely pair. She was one of the faces of swinging London, a Neasden girl from a working-class background who, while still a teenager, had become an international celebrity on the back of her modelling. Nicknamed Twiggy on account of her skinny legs, Lesley Hornby had been discovered in a hairdressing salon. He was from an older generation: a dapper, quintessential Englishman who had been very famous indeed since the 1920s. He was a playwright, an actor and a songwriter who had written plays and appeared in or scripted several films long since accepted as classics.

Noël Coward and Twiggy seemed to belong to different worlds but their paths crossed, and this weekend Twiggy will be introducing a screening of Blithe Spirit at the Noël Coward Film Festival in London.

It was in 1968, Twiggy remembers, that she first met Coward. She was on holiday in Jamaica with her friends Tommy Steele and his wife, Annie. Coward lived up the road. “We went to tea. That was how I first met him.”

True to his reputation, Coward turned out to be “ very grand, very theatrical”. This was a man who lived in a world of drawing room comedy and silk dressing gowns. She was the Sixties waif with the short hair, beanpole body and the very big eyes.

“It wasn't really my kind of world,” she says of Coward's milieu. “I was very young and very unsophisticated and he was… this great man,” Twiggy remembers. “I knew him because of my mum and dad; it was their era really. I knew a couple of the songs, like 'London Pride' and things like that. I wasn't aware how terribly talented he was until afterwards really. I hadn't seen any of his plays at that point.”

Coward was “charming” to the young model and even mollycoddled and played with Tommy Steele's baby daughter. He was, she remembers, “very Noël Coward”. Ask her precisely what that means and she mimics Coward. “It was the voice really, that clipped old English way of speaking, slightly over the top and slightly camp and the way he appeared, with a never-ending cigarette in his cigarette holder and his dressing gown, that suave elegance. He was so stylish, wasn't he? It wasn't till years later, after he died, that I realised how much he had written. No wonder they called him the Master.”

Noël Coward's career had indeed been prodigious. His relationship to cinema stretched back to the silent era. His play The Vortex, about high society, drug abuse and family strife, had been filmed in 1928 with the Welsh matinee idol Ivor Novello in the leading role. The 1933 adaptation of his play Cavalcade won three Oscars. There were various film versions of Private Lives, which seems in hindsight like the original battle-of-the-sexes romcom. Showing that he was capable of far more than comedy or upscale Mayfair drama, Coward gave a staunch performance as the Louis Mountbatten-like naval commander in the wartime propaganda picture In Which We Serve (1942), which he also scripted, produced and directed (alongside David Lean.) Long before EastEnders and TV soap operas, he collaborated again with Lean on This Happy Breed (1944), a film adaptation of his play about the everyday life of a London family in peace and in wartime.

Coward may have been gay, but long before he met Twiggy he numbered glamorous actresses, models and society figures among his huge circle of confidantes. Nancy Mitford was his “pen pal”. There was Lady Diana Cooper, the English aristocrat, and Gladys Cooper, the actress and noted beauty who exasperated Coward by forgetting her lines when she played the Countess of Marshwood in Relative Values. There was Greta Garbo, with whom the press (somewhat ludicrously) suggested he was having an affair. As Philip Hoare notes in his biography of Coward, “such publicity was not unwelcome as it diverted attention from their individual predilections.”

The playwright was friends for many years with Marlene Dietrich and knew Jean Harlow. Tallulah Bankhead, who appeared in the first production of Coward's Fallen Angels and enjoyed great success in a revival of Private Lives, was a chum and drinking partner. He was a guest at parties hosted by Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. He was close to Vivien Leigh (“She is such a darling when she is all right and such a conceited little bitch when she isn't all right,” he wrote of her in his dairy.) There are pictures of him with Ava Gardner. He was very close to Judy Garland.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Perhaps the real measure of Coward's fame was the fact that his name was on the hit list in the “black book” of British people whom Adolf Hitler wanted killed – and this despite Coward having written his famous wartime ditty, “Don't let's be beastly to the Germans”.

Having been a “bright young thing” in the 1920s, the dapper old-timer had even made his own contribution to the swinging Sixties by appearing with Michael Caine as a very well-spoken criminal (“the Mafia – they will be waiting for you!”) in The Italian Job. Ian Fleming was his friend and neighbour in Jamaica and reportedly sought out his thoughts on James Bond. He was invited to the White House by President Roosevelt.

By the time Twiggy met him in Jamaica, Coward was one of the best-connected men of the 20th century. After he came back to England when his health was declining at the end of his life (he died in 1973), Twiggy stayed in touch. Her friends the actors Maggie Smith and Robert Stephens used to visit Coward in hospital and bring him a “surprise” every day. On one occasion, Twiggy was chosen as the surprise. She burst into his hospital room and he was delighted to see her. “We had a jolly time. He was always telling funny stories.”

When Coward was out of the hospital, she would meet him for tea at the Savoy. “At that point, it must have been 1969, I was rehearsing for The Boy Friend, the film I did with Ken Russell,” Twiggy recalls. The Boy Friend was a musical set in the 1920s – so who better than Coward to give the model-turned-actress some tips? “I was learning to tap dance. He said, 'Show me some of the steps, show me some of the steps.” At Coward's bidding, Twiggy performed an impromptu routine in Coward's suite at the Savoy which, she remembers, had a marble floor. There was a knock at the door. “He said, 'Come in come in!' and in walked Merle Oberon. I was overcome!” The glamorous Hollywood star of Wuthering Heights and The Dark Angel was one of Coward's firm friends. It's a nice image – one of the biggest celebrities of the 1960s starstruck by someone by then far less well known than she was. “It was quite overwhelming. Although I was very famous by then, I wasn't that worldly.”

Coward told Twiggy that one day she should play Elvira, the beautiful wife summoned back from the dead by Madame Arcati in Blithe Spirit. At the time, Twiggy, who didn't know the play, thought nothing about the suggestion. Later, she played the mischievous spouse in two productions, first at Chichester alongside Dora Bryan in 1997, then at the Bay Street Theatre in Long Island in New York in 2002. (“Twiggy is a magnificent hallucination, a classic Elvira of the spirits,” The New York Times enthused.)

Over the years, Twiggy has seen most of Coward's movies, everything from The Italian Job to In Which We Serve. She saw Brief Encounter too and suggests that its depiction of an adulterous affair must have been “quite shocking” for 1940s audiences. But, no, she wasn't aware that many critics had interpreted it in terms of Coward's experiences as a closeted gay man.

These days, Twiggy designs popular collections for Marks & Spencer. I contemplate asking whether she thinks Coward would have looked good in M&S garb but decide against it. Instead, I ask as a final question if she thinks Coward's work and life still have meaning for a younger generation?

“I think he [Coward] is very current. It's like Terence Rattigan, isn't it? He went out of fashion for a bit, didn't he, but then, suddenly, people think blimey, this is wonderful!” Twiggy reflects. “I just feel very, very lucky that I met him.”

The Noël Coward Festival runs at Regent Street Cinema, London W1, 20-22 November. Twiggy will introduce a screening of 'Blithe Spirit' on 21 November (www.regentstreetcinema.com/noel-coward-film-festival)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments