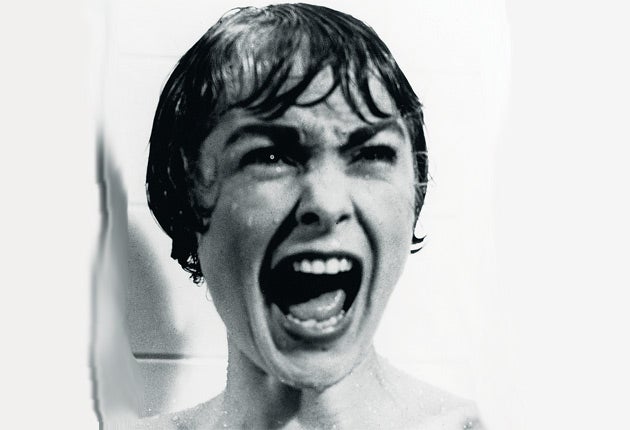

They made the critics scream, but now these films are classics

Fifty years ago both Psycho and Peeping Tom – Michael Powell's masterpiece about a serial killer with a camera – were condemned. Geoffrey Macnab explores how we changed our minds about them, and others

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is 50 years now since the beatific-faced Carl Boehm played a duffel-coat wearing serial killer, trying to catch the moment of his female victims' death on camera, in Michael Powell's Peeping Tom (1960.) The critics were utterly dismissive of what is now considered one of the most influential films in British cinema history. Tabloids and broadsheets were equally coruscating. Powell's masterpiece was "the sickest, filthiest film I remember seeing," according to The Spectator, "loathsome", at least to Alexander Walker of the London Evening Standard, "perverted nonsense" in the eyes of the Daily Worker; worthy only of being shovelled up and flushed "swiftly down the nearest sewer" in the words of Tribune. The Observer's critic professed herself "sickened" before making an indignant and early exit from the press screening.

"They cancelled the British distribution, and they sold the negative as soon as they could to an obscure black-marketeer of films who tried to forget it, and forgotten it was, along with its director, for 20 years," Powell wrote in his memoir Million-Dollar Movie.

The story of how Peeping Tom was championed by Martin Scorsese (among others) has often been told. In hindsight, it is apparent that the critical revulsion toward the film was prompted not by its formal or aesthetic shortcomings but because of its subject matter. A self-reflexive film about scopophilia and the murderous gaze was never likely to appeal to British reviewers of the period. Even the ones who hated it the most acknowledged that Powell had "remarkable technical gifts" and praised the acting and cinematography. Their gripes were with a story (by Leo Marks) driven by "sadism, sex, and the exploitation of human degradation."

Peeping Tom is far from the only film reviled by critics and distrusted by audiences on its first appearance and then reclaimed as a masterpiece a short while later. Only a few weeks after the release of Peeping Tom, several British critics were similarly discomfited by Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho. "Psycho analysis – I didn't like it," quipped the headline of the London Evening News review. After listing all the scenes he disapproved of ("a naked girl being grabbed over and over again when she takes a shower," "a young man preserving with chemicals the body of his mother whom he has murdered"), the reviewer concluded that "Hitchcock has tarnished a once great reputation."

The Evening Standard's Alexander Walker called Psycho as "a stomach-churning, nasty essay into horror... what nauseates one is [Hitchcock's] sick relish of anything in it that is perverted or blood-spattered. And much is." Meanwhile, The Daily Telegraph called the film "a curious, disappointing piece which, for all its modern setting and psychological background, recalls old-fashioned or Victorian melodramas by its very absurdity." The veteran British director seems to have factored in a measure of critical revulsion as a useful part of the marketing campaign. The mixed notices did nothing at all to dent the box-office returns for Psycho.

One film now acknowledged as a cast-iron modern classic but almost destroyed at birth by critical bile was Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967). "A cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick comedy... it leaves an astonished critic wondering just what purpose Mr Penn and Mr Beatty think they serve with this strangely antique, sentimental claptrap," Bosley Crowther, the all-powerful critic of The New York Times, fulminated. Crowther was a representative of the old guard. He didn't like the combination of slapstick and lurid violence in Bonnie and Clyde. Nor did he appreciate "Miss Dunaway squirming grossly as his thrill-seeking, sex-starved moll". Other US reviewers were hostile too. Time magazine decided that the real fault with Bonnie and Clyde was its "sheer, tasteless aimlessness". New York magazine decided that "slop is slop, even served with a silver ladle."

These critics' hostility risked being as lethal as the machine-gun fire at the end of Bonnie and Clyde when it came to the film's commercial prospects. Thankfully for Warren Beatty and Co, their movie was championed by a new generation of critics including Pauline Kael in The New Yorker and her rival Andrew Sarris in The Village Voice. After its lacklustre US opening, it was eventually re-released to Oscars, huge acclaim and box-office success. Some of its original detractors even revised their views, belatedly accepting that the film was ground-breaking and that its use of violence was justified.

The US critics' disdain for Bonnie and Clyde was matched by the contempt that the French in 1939 showed toward Jean Renoir's The Rules of the Game. The film now regularly nestles close to the top of critics' polls but was a disaster on its original release. Renoir was attacked for having had the gall to satirise the French aristocracy on the eve of the Second World War. The film did no business at the box-office and ended up being banned by the Nazis anyway. "I wanted to depict a society dancing on a volcano," the director said of his portrayal of the frivolous upper-classes, seemingly oblivious to the historical forces that were about to engulf them. Audiences in late 1930s France were in no mood to heed Renoir's warnings.

Throughout cinema history, visionary directors have often left audiences and critics baffled. Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey attracted barbs. The Los Angeles Times complained about its "deliberate obscurantism." Renata Adler in The New York Times complained about what she thought "a very complicated, languid movie... so completely absorbed in its own problems, its use of colour and space, its fanatical devotion to science-fiction detail, that it is somewhere between hypnotic and immensely boring".

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Michael Cimino's Heaven's Gate, seen as a masterpiece by many Europeans, flopped at least partly because the influential critic Vincent Canby suggested, in The New York Times, that watching it was "like a forced, four-hour walking tour of one's own living room."

There are plentiful recent examples of films being dismissed by critics before being fast-tracked into the canon of modern classics. "War may be hell, but watching war movies can also be hell, especially when they don't get to the point," trade paper Variety wrote of Kathryn Bigelow's Oscar winner The Hurt Locker, adding that the film didn't "bring anything new to the table of grunts-in-the-firing-line movies."

Now that they're reached the grand old age of 50, both Peeping Tom and Psycho have attained a respectability that would have seemed very unlikely back in 1960. Rather than being flushed down the nearest sewer, the former is likely to be the subject of earnest articles and highbrow TV and radio discussions when it is re-released later this year. Psycho, meanwhile, is probably Hitchcock's best-known film, endlessly revived and imitated.

You can't accuse critics and audiences of simply getting it wrong. They called it as they saw it. Those reviewers who savaged Peeping Tom or cinema-goers who booed The Rules of the Game were (one must assume) behaving with all sincerity. They didn't like what they were seeing on screen and they found their own ways of expressing their disdain. Years later, these films have been reassessed and the original verdicts against them have long since been set aside. Powell lived to see his reputation rehabilitated, even if he was living in poverty in a cottage in the Cotswolds when Martin Scorsese began to champion his work.

But you can't help but feel a nagging suspicion that some film-makers whose work has been reassessed will miss their old notoriety. After all, although bad reviews can be immensely damaging, there is nothing quite as deadening as critical respectability.

'Peeping Tom', 50th anniversary release, is scheduled for September. 'Psycho' 50th Anniversary Edition will be available on Blu-Ray Hi-Def on 9 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments