The Square film's dinner scene: How the most tense, uncomfortable scene of the year was achieved

Motion capture performer Terry Notary harnessed his CGI ape skills to destroy a room full of stuffy art benefactors

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

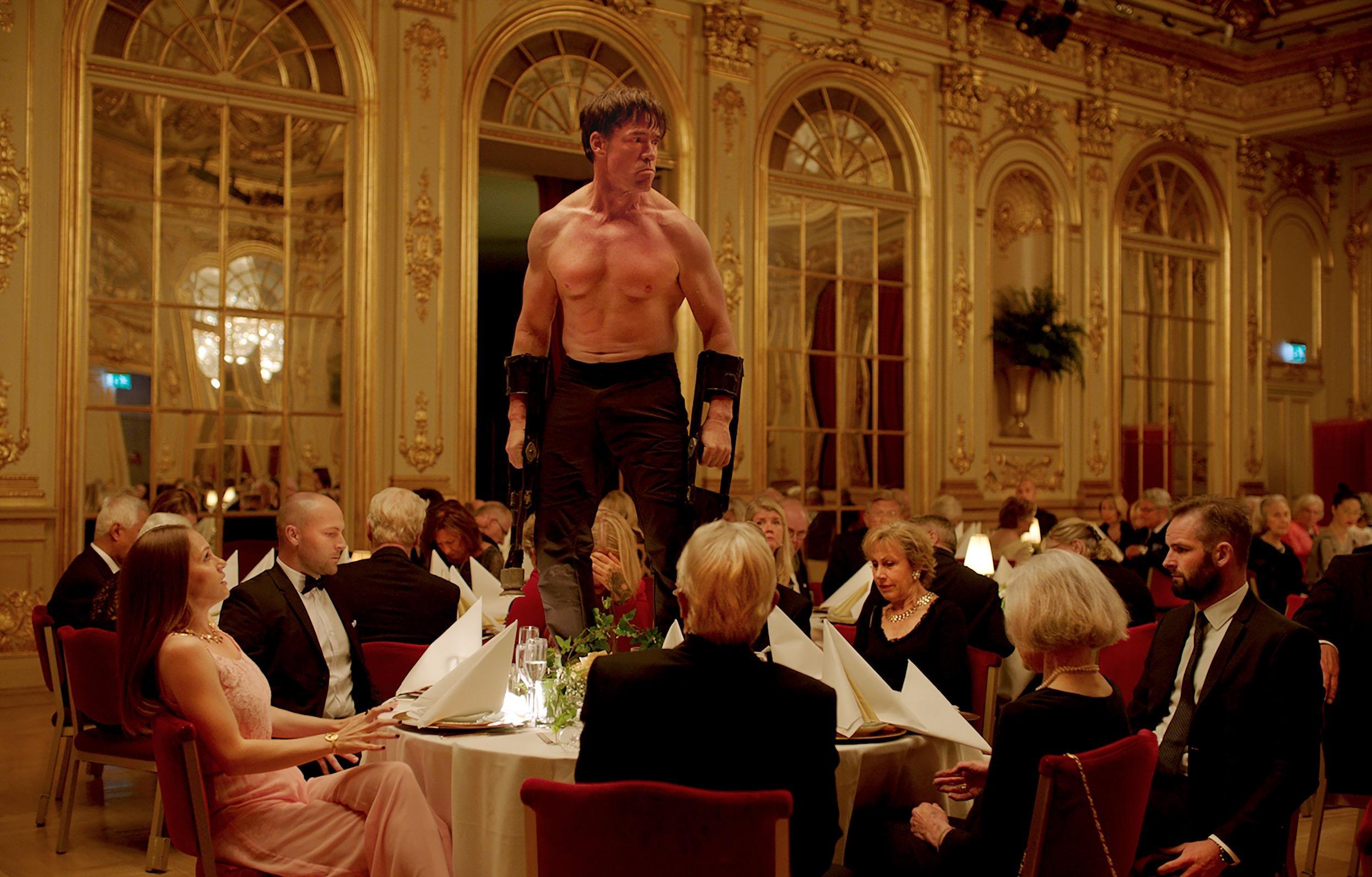

Your support makes all the difference.Ruben Ostlund’s Palme d’Or-winning film The Square satirises class and the art world in a number of brilliant ways, but by far the most memorable scene takes places at a fancy dinner (watch an exclusive clip from it above).

In it, guests are told there will be an art performance ahead of their entrées, which turns out to be a half-naked man acting like an ape – barking at diners, singling them out, tossing furniture, smashing plates and generally intimidating people. I won’t spoil how the scene progresses (you can catch The Square in cinemas now), but it goes to some pretty dark places and is quite hard to watch. Imagine that scenario where someone’s being difficult on the bus, but cranked up to a thousand.

The performance artist was played by Terry Notary, whom you won’t recognise despite him having appeared in major franchises such as Avengers, Avatar, Planet of the Apes and X-Men as he normally does stunts and motion capture, lending his movements and expressions to a film but never his likeness.

I caught up with him to get answers to a few questions the jaw-dropping scene left me with.

So was your character playing an ape? Or a man playing an ape? Or a man playing a man playing an ape?

We didn’t really talk about it, I just tapped into a friend of mine from Cirque Du Soleil, this Russian acrobat who was also a bit of a gangster. We were friends, but he was one of those sort-of Wild West types who carried a gun, didn’t care if you liked him or not and was always after the truth. He was really nice and funny but then all of a sudden horribly scary. One night, we were drinking until nine in the morning, as Russians do, and everything was great, but then all of a sudden another Russian across the table said something to him and it switched instantly and he just punched him really hard in the face. There was a huge fight for maybe 45 seconds and then all of a sudden they were hugging each other and it was all better. It was one of the scariest things I’ve ever witnessed in my life, how they could switch emotionally like that. I wanted to channel that and emulate bullies and how they always want an audience.

Did the cast and extras have any idea how far things would go?

It kind of took on a life of its own. The direction was, “Make your way over to this area and just do whatever you want along the way.” I knew emotionally where Ruben [Ostlund, director] wanted to go and he gave me free range. The extras were all people from the real art world – I had no idea, I thought they were extras getting paid $200 a day to be there. I assumed we were going to lose a few on the first day but they all came back, I was really impressed. Several came up to me and said, “Oh if you want to pick me I’m fine with it, you can push me around, drag me around – whatever you want to do.” And I was like, “OK, good, I won’t choose you then.” I didn’t wanna choose anyone who wanted to be picked. I went up to the people who didn’t want to and basically tried to feel what they didn’t want to happen and then allowed that to happen.

How did your interaction with Dominic West’s character [a respected artist and key guest at the dinner] work?

I said, “OK, he’s the alpha in the room, you have to chase him out and become the alpha.” And so we met, had no rehearsal, and I just said, “Love your work man, let’s see what happens.” We did that take twice and I thought what would be the most shocking thing would be to just scream at him and see what happens. Scream so loud that it almost hurts his ears.

So when he’s responding by trying to make a joke out of it, that all happened in the take?

Yeah, and I was not having that. “No, no, no, you’re not going to make a joke of this, you’re the joke.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Did it get a bit meta, with people thinking things were going too far not just in the scene but on the actual film set?

We had that happen a few times. Real dishes breaking and crashing, glasses being tossed, people being thrown down. It took it to the next level which I think needed to happen because it kept the unpredictability in the room.

So some people were freaked out?

Yeah, and those were the people I wanted to target. Those were the best reactors because they just didn’t want to be dealt with and had all that internal stuff going on – “Please, don’t touch me” – that was the tension that we needed in order to build the silent moments, because it was more about the moments in between the moments of action. I call it “the drawing of the bow”, you know when you draw a bow and aim the arrow, when you’re stretching the string tighter and tighter and tighter, that’s when it’s interesting for me, once you shoot the arrow it’s over and you have to start over again somewhere else. So basically we wanted to draw the bow as long as possible so that it would build that tension, so you’d be like, “Holy s***, when is this going to end, how far are they gonna take this thing and oh my God what’s going to happen next?” I didn’t feel rushed.

Did you feel nervous about what you were about to do these people?

Yeah! I always feel nervous, I always feel fear, but if I don’t feel them I feel nervous about not feeling them! When I’m scared I embrace the fear and use it.

What do you think was your character’s motivation for doing what he did?

He was using his way of being an ape as this mask that could allow him to expose the truth and the weakness in the room, the weakness of humanity and all this pretence and falsehood of who we think we are. Hiding in the masses – that’s what I wanted to expose. If I’d had dialogue I would have said, “How long and how far do I have to go to get you to fall out of your complacency, to get off your asses and do something? Do I have to rape this girl?” At the end I kind of wish I’d spoken and said, “Excuse me, enjoy your meal, I’m going to go check on the girl I almost raped while you sat there in your fancy suits, make sure she’s all right.” So that was his inner dialogue, basically, “f*** you and your pretence”.

Do you think the curator who commissioned the performance planned it to go that way? Or was the guy just crazy, or did he take it too far intentionally because he was angry about the viral ad gone wrong we see earlier in the film?

The curator did not expect it, it was taken way too far. In the film I think my character’s performances in previous installations were not as aggressive, this turned out to be a moment where he started to lose control and make a point about the room, a f***-you. He didn’t give a s*** what the curator thought.

We knew that we wanted to take it the point where I dragged the girl away, and then we said, “What if I just start to try and mount her and go that far? If we’re going to the nth degree let’s just take it there, we can always cut it out.” It felt like a good way to end it, a good way to really go, “Oh my god that’s it, you can’t take it any further than that unless you’re going to kill somebody.” And then the guests turn into beasts and he turns into the victim in the end, and I like that twist. They turn into the primal animals.

Just ‘coz of their own ego, because they feel like if they don’t join in they’ll look emasculated.

Yeah, and everyone can relate to that – you know, “What is the first person gonna do? OK, the second person’s waded in, ah, do I go in now?”

Do you think the scene will make people better appreciate the work that goes into this type of performance, which is usually only used for motion capture?

I think so, I really do, because I’ve had a lot of conversations with other actors about it where they’re like, “Dude, that was insane, how did you do that how did you get there [mentally]?” But I’ve been doing that for 15 years! The only people that normally see it are the director and maybe a couple of actors on set.

‘The Square’ is in cinemas now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments