The Red Turtle: Director Michael Dudok de Wit on his unique collaboration with Studio Ghibli

The Dutch-British animator discusses the beloved Japanese studio and the artistic licence it gives its directors

Studio Ghibli is in a strange and fluctuating state at the moment, pushed and pulled by the various retirements and unretirements of founding member (and most celebrated contributor) Hayao Miyazaki; only this year, he came out of his announced retirement from 2013 with the intention of working on a new feature film.

After Miyazaki's initial retirement, studio said it would taking a break to re-evaluate its approach, prompting fears it may even shut down.

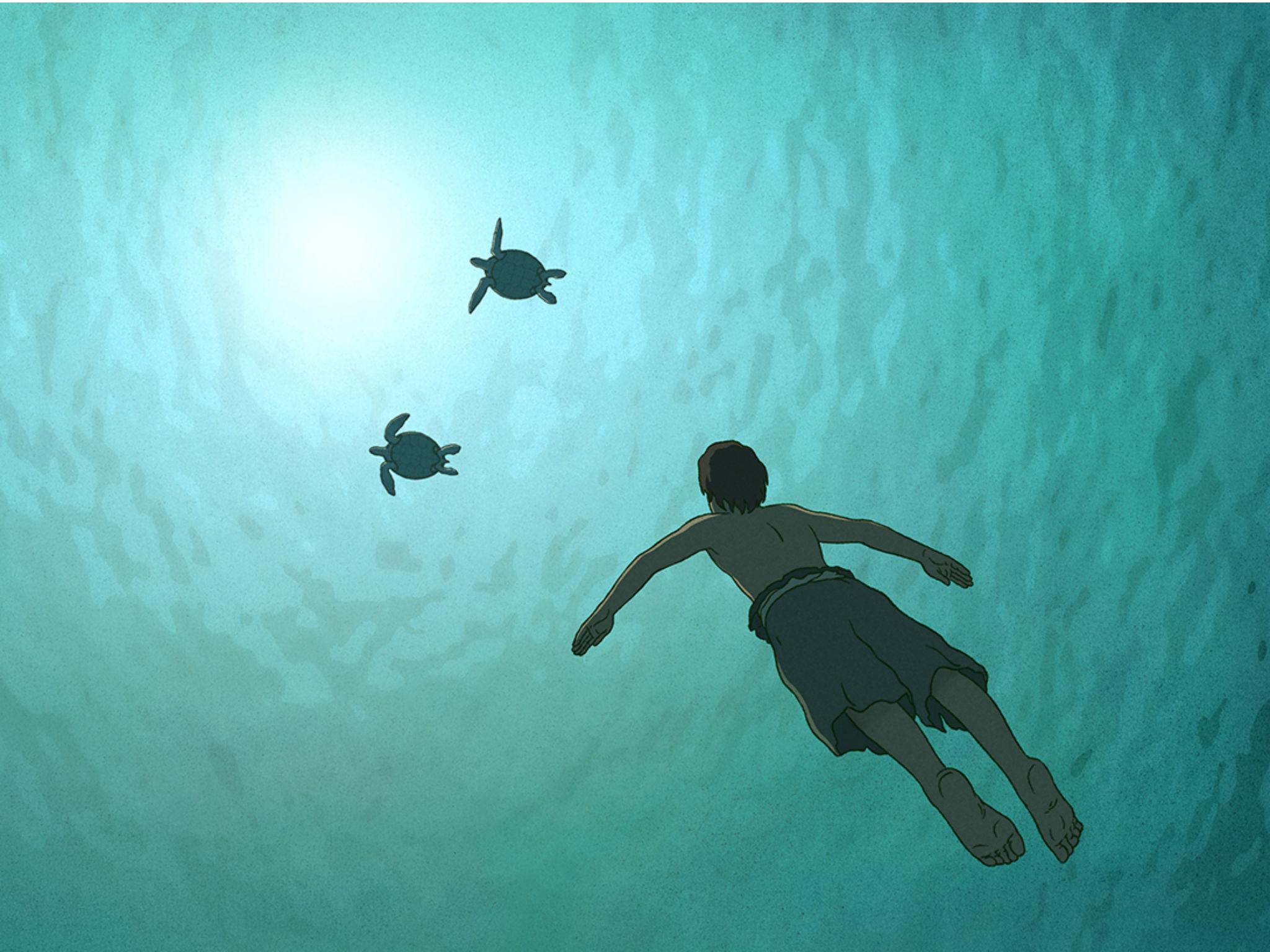

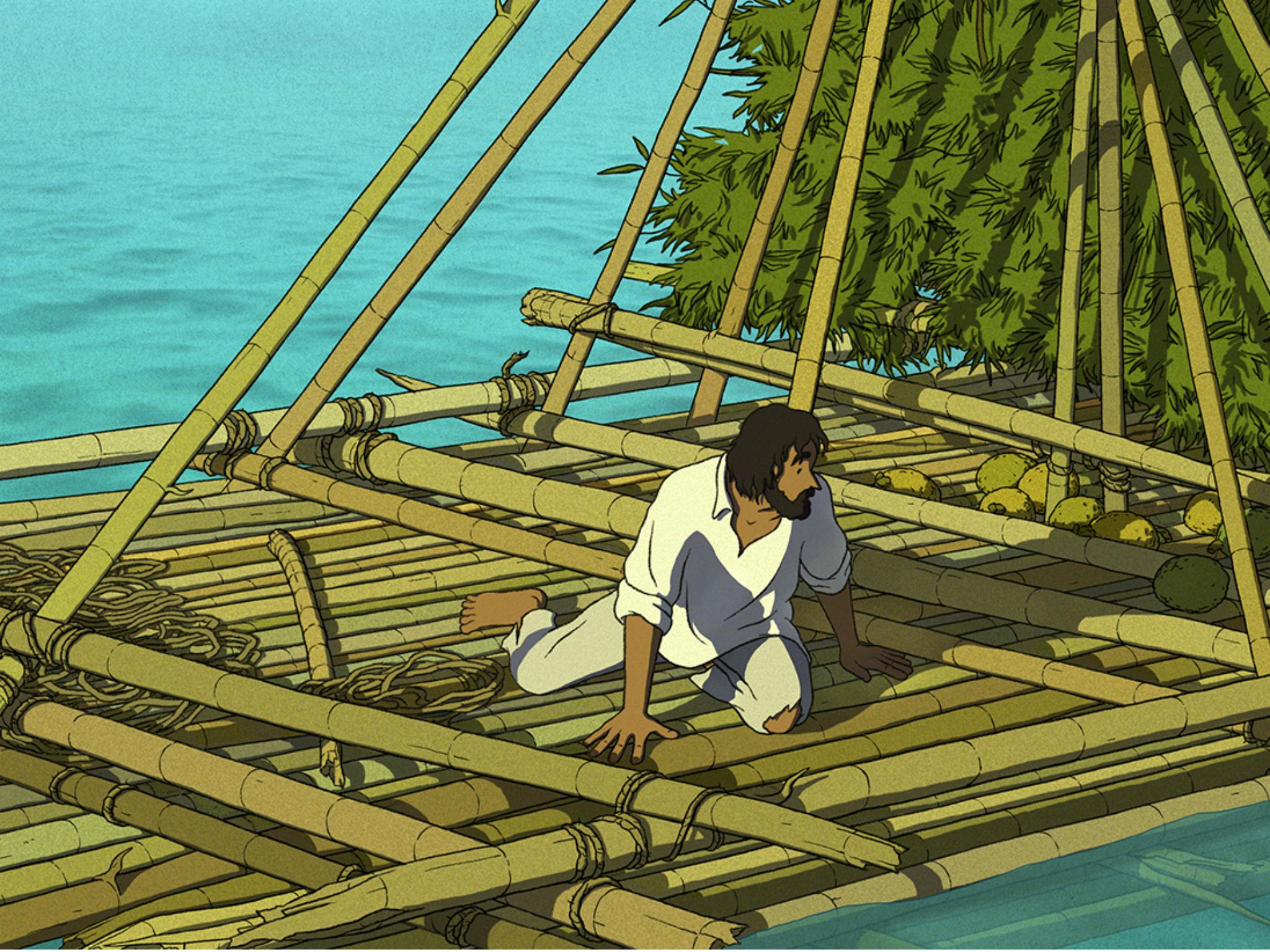

Far from it: Ghibli has instead branched out and expanded its line of creative sight, launching into a co-production with distribution company Wild Bunch on Dutch-British animator Michael Dudok de Wit's The Red Turtle, the beautiful and simple tale of a man who wakes up on a deserted island to find strange companionship with the film's titular brightly coloured creature.

The film first debuted at last year's Cannes Film Festival, where it was critically acclaimed, before a run at the London Film Festival in October.

We spoke to Dudok de Wit about his incredible collaboration with the studio, from the inspiration he took from their animation to the trust and freedom he found Ghibli offers their directors.

Studio Ghibli specifically asked you to take on The Red Turtle after seeing your short film? Is this true?

It’s almost unbelievable, but yes, it is true: the producers at Studio Ghibli asked me, out of the blue, to write and direct an animated feature. They added that this feature would be co-produced by Studio Ghibli and Wild Bunch, their international distributor in Paris.

What was it like when you received the news? It must have been an amazing feeling!

It was, and it took me months to come down. Meanwhile, I didn’t mention it to anyone. There were too many uncertainties and besides, both the Japanese producers and I tend to be very discreet with new projects.

Did you feel under pressure to adapt your style in any way to fit with Studio Ghibli?

I felt no pressure, on the contrary. The producers at Studio Ghibli asked me to propose a story and to propose a visual style. If we go ahead with this project, they said, it will be made entirely in Europe with European artists. Studio Ghibli has a tradition of making director’s films, in other words, on the artistic level the director has the final say.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Was I influenced by the style of Studio Ghibli? I didn’t try to emulate the style, I would not be good at that anyway, but on a subconscious level I was inspired. I must have been, because I deeply admire their work, especially the films by Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki.

Were there any changes you had to make to your approach, either aesthetically, or tonally?

My visual approach varies from project to project. With this long film project I felt that I had to put more details into the landscapes than I have ever done before in my films, while at the same time I wanted to explore the beauty of simplicity. This may sound like a contradiction, but it wasn’t really; it was a very interesting challenge. During the first months I created half a dozen colour images to establish the look of the film – to be specific, to indicate the charcoal-based technique, the quality of the line, the colours and the amount of detail – and the producers liked the images straight away.

During the development phase, which lasted almost five years, I would often meet them and they expressed their opinions with frankness, but they didn’t impose changes.

What do you think the difference between Japanese and Western animation is?

There are a few obvious ones. In Japanese animation human faces tend to have huge eyes, the body language reflects the body language of Japanese people and Japanese animation tends to have less drawings per second, but the drawings are of a higher quality, generally speaking. In my opinion the use of the imagination in Japan differs from the use of the imagination in the West, but I find it hard to point out what the essential differences are. They can be subtle. The Japanese imagination adds an unusual and highly interesting quality to their animated films. The Ghibli films convey a strong sensitivity to nature, stronger than films made in the West.

The film seems quite surreal and open-ended. Have you heard different people's interpretations of the story and do you enjoy hearing those opinions?

I have indeed heard a few different interpretations and I enjoyed hearing them, because they confirmed to me that our intentions with this film were working for the spectators. To my relief, many people love the fact that the story of The Red Turtle is relatively open at times. Not all, but many.

Do you prefer films that involve a level of interpretation?

Not necessarily, some of my favourite films have stories that are told in a clear and solid manner, while others have a sensitive, fine-tuned openness. Of course, all films are open to interpretation to a degree, whether we realise it or not. That’s what I love about film language; it’s a language that can speak to us on an intuitive level.

Why did you choose to make the creature a turtle?

It felt right. When the idea came to have a large sea turtle interacting with the main character in the story, I was deeply happy, because I felt confident that it would work.

What is the significance of the animal to you – and why red?

The turtle has a combination of significance to me. For instance, she is clearly totally one with nature; by swimming alone for thousands of miles, she belongs to the infinite space of the ocean, to infinity, yet she can also move on land and breathe air like we do; she conveys the feeling that she is immortal; she is peaceful; she is magnificent yet not too sweet, with her carapace and her reptilian face.

The colour red makes her stand out from the ocean and it differentiates her from the other turtles. It’s a colour that suits her, I find.

What was the reaction from Studio Ghibli when they saw the first cut?

Actually, there was no real first cut moment, like one can have in live action films. The Japanese producers saw the progress of the film step by step, and the French producers did too, so there was no sudden discovery. Even the music was heard in stages.

'The Red Turtle' is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments