The man who drew himself into a myth: Mourning Hayao Miyazaki's retirement

The Japanese auteur revolutionised animation with his films for Studio Ghibli

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There’s good news and there’s bad news for animation fans. The good news is that Japan’s Studio Ghibli, the company behind many of cinema’s most gorgeously idiosyncratic cartoons, is about to release its latest film, The Wind Rises. In addition, the BFI’s two-month Ghibli retrospective is under way, so now’s the time to see spotless prints of Howl’s Moving Castle and My Neighbour Totoro on the big screen.

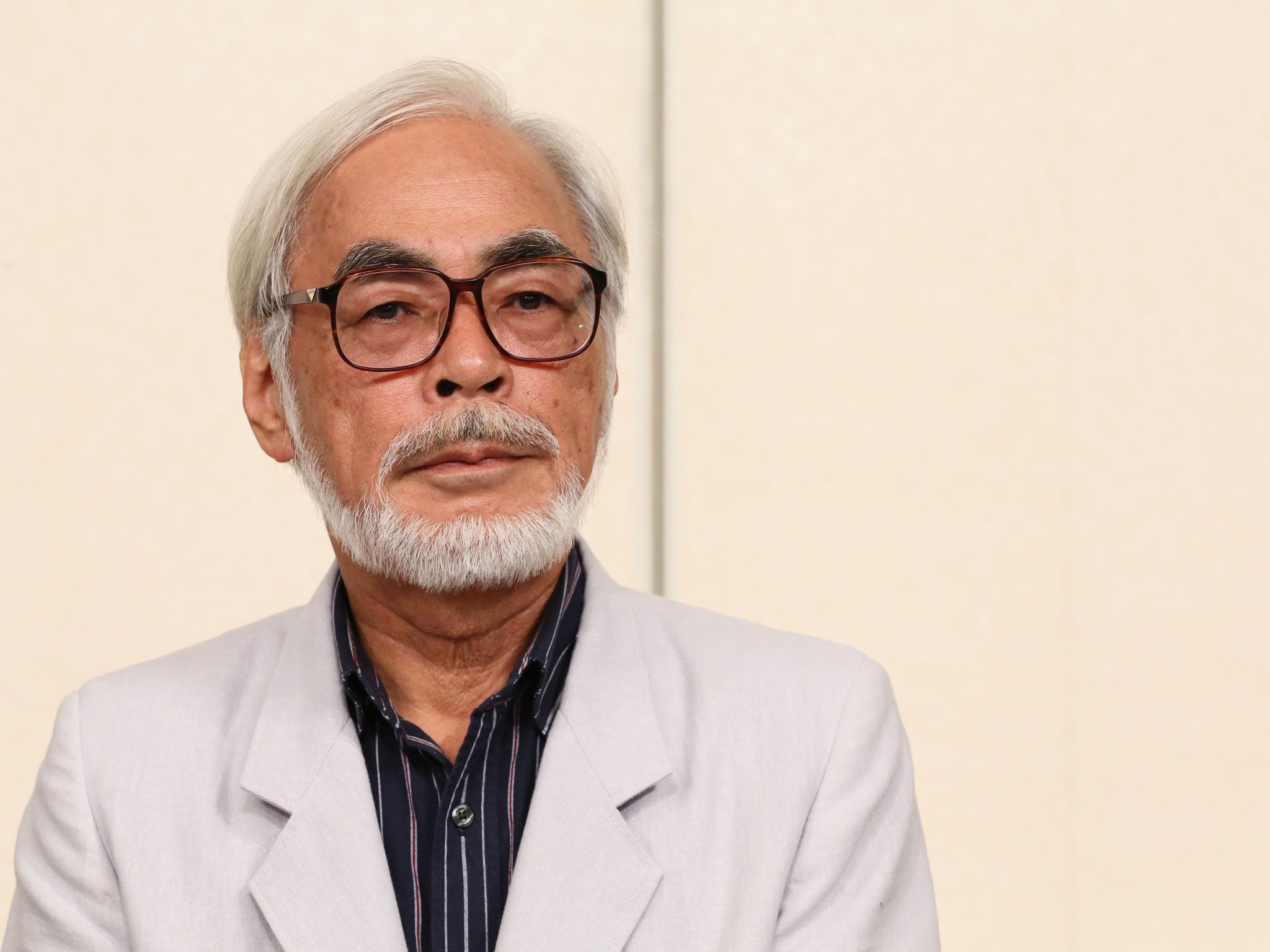

The bad news is that Hayao Miyazaki, the company’s 73-year-old co-founder and guiding light, has announced that The Wind Rises will be the last film he directs. Kitaro Kosaka, the film’s supervising animator and Miyazaki’s regular right-hand man, puts his boss’s retirement in perspective. “Studio Ghibli is a studio that exists in order to create Hayao Miyazaki’s films,” he says. “His philosophy and the way he lives his life are connected at a fundamental level with all of his works, and his attitude towards everything is reflected in the characters. It’s like watching a child when you see him drawing, constantly doing his own sound effects.” So what will the Studio do when he isn’t drawing there any more?

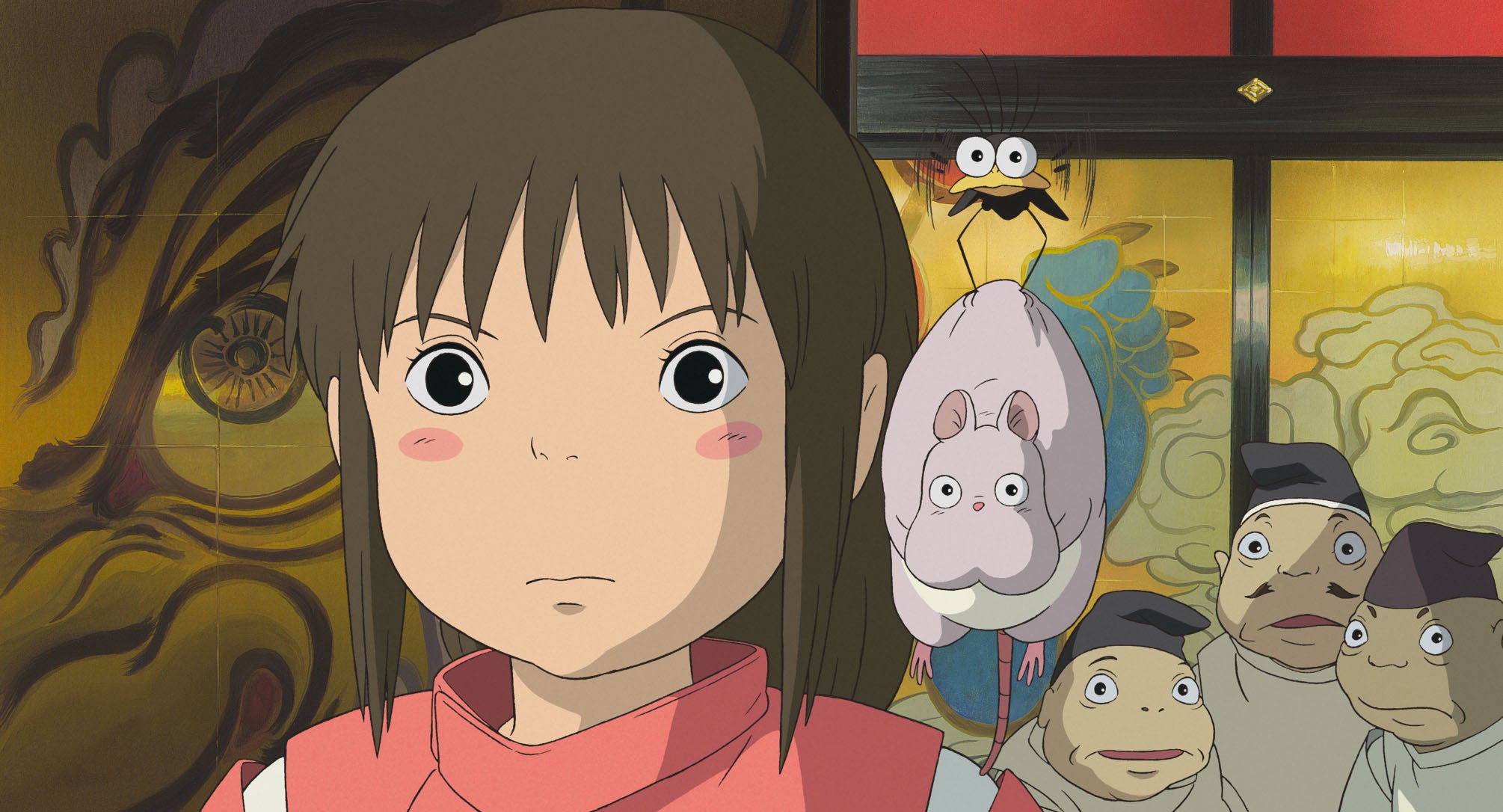

Ghibli was set up nearly 30 years ago by Miyazaki and his long-term collaborator, Isao Takahata; a decade before that, in 1972, they had first worked together on a half-hour cartoon with the only-in-Japan title, Panda! Go, Panda! Since then, their films have been fabulously diverse. Miyazaki’s 1992 work Porco Rosso, for instance, features the barnstorming escapades of an ace fighter pilot who happens to be a pig, while Takahata’s 1988 classic Grave of the Fireflies could well be the most drainingly grim war movie ever made. The company’s founding film, 1984’s Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, directed by Miyazaki and produced by Takahata, is a post-apocalyptic sci-fi adventure, while Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, which won the 2003 Oscar for Best Animated Film, sees a 10-year-old girl working in a bath house for ghosts and demons. But as far-ranging as Studio Ghibli’s films are, the majority are linked by their gentle pacing, compassion, spooky surrealism, fascination with unspoilt nature, utterly authentic pre-teen protagonists, and conviction that modern Japan is only a whisker away from an extraordinary realm of fairy tale: think Lewis Carroll, as illustrated by Hieronymous Bosch.

And it is Miyazaki who has defined Studio Ghibli’s style. The company has released films by other directors – including five by Takahata and two by Miyasaki’s son Goro – but it is Miyazaki who is revered by those who prefer their cartoons to be more esoteric and evocative than standard Hollywood fare.

“The outstanding characteristic of Mr Miyazaki’s work,” says Kosaka, “is that he transfers himself into the things he is drawing. Therefore, even in a fantastical universe, there is a strange feeling of reality. There is a Japanese proverb, ‘Don’t carve the Buddha without putting your soul into it’, which basically means that we don’t settle for things that have been made in a perfunctory manner.”

It’s a philosophy that has brought Miyazaki a devout following in the West. Pixar’s John Lasseter, an old friend, has called Miyazaki “the world’s greatest living animator”. My nieces, aged nine and 12, would agree. Quite apart from the extravagant imagination of the films, what’s so thrilling about them is their use of hand-drawn characters on lushly hand-painted backgrounds, with minimal help from computer-generated imagery. When Miyazaki was directing the 1997 epic Princess Mononoke, he drew 80,000 of the film’s frames himself.

Geoffrey Wexler, the chief of Studio Ghibli’s International Division, has no doubt that such mind-boggling feats are worth the effort. “The attention to detail and the hand-drawn quality really touches people of all ages,” says Wexler, an American based in Tokyo. “The films are akin to a beautiful piece of music or a splendid painting. You might not know why it touches you so much, but it does. I also think the stories are wonderfully complex. They don’t explain much, they leave it to the audience to figure things out for themselves. And our characters don’t keep to the lines of good or evil. They can be kind, and then do something quite unattractive. They have vagueness and ambiguity. They confound our expectations. I never know what to expect when I watch one of our films, even though I’ve read the screenplays and looked at the storyboards.”

In comparison to a Studio Ghibli production, even the most inspired of American cartoons can seem glib and formulaic. On the other hand, the “vagueness and ambiguity” extolled by Wexler may explain why Miyazaki’s films remain cult hits in the West, rather than the blockbusters they are on their home turf. “Vague storytelling doesn’t go down as well in America as it does in other countries,” laments Wexler. “What’s more, our films aren’t computer-generated and they’re not in 3D, so they’re not just perceived as foreign films in America; they have multiple levels of foreignness. There are a lot of battles still to be won.”

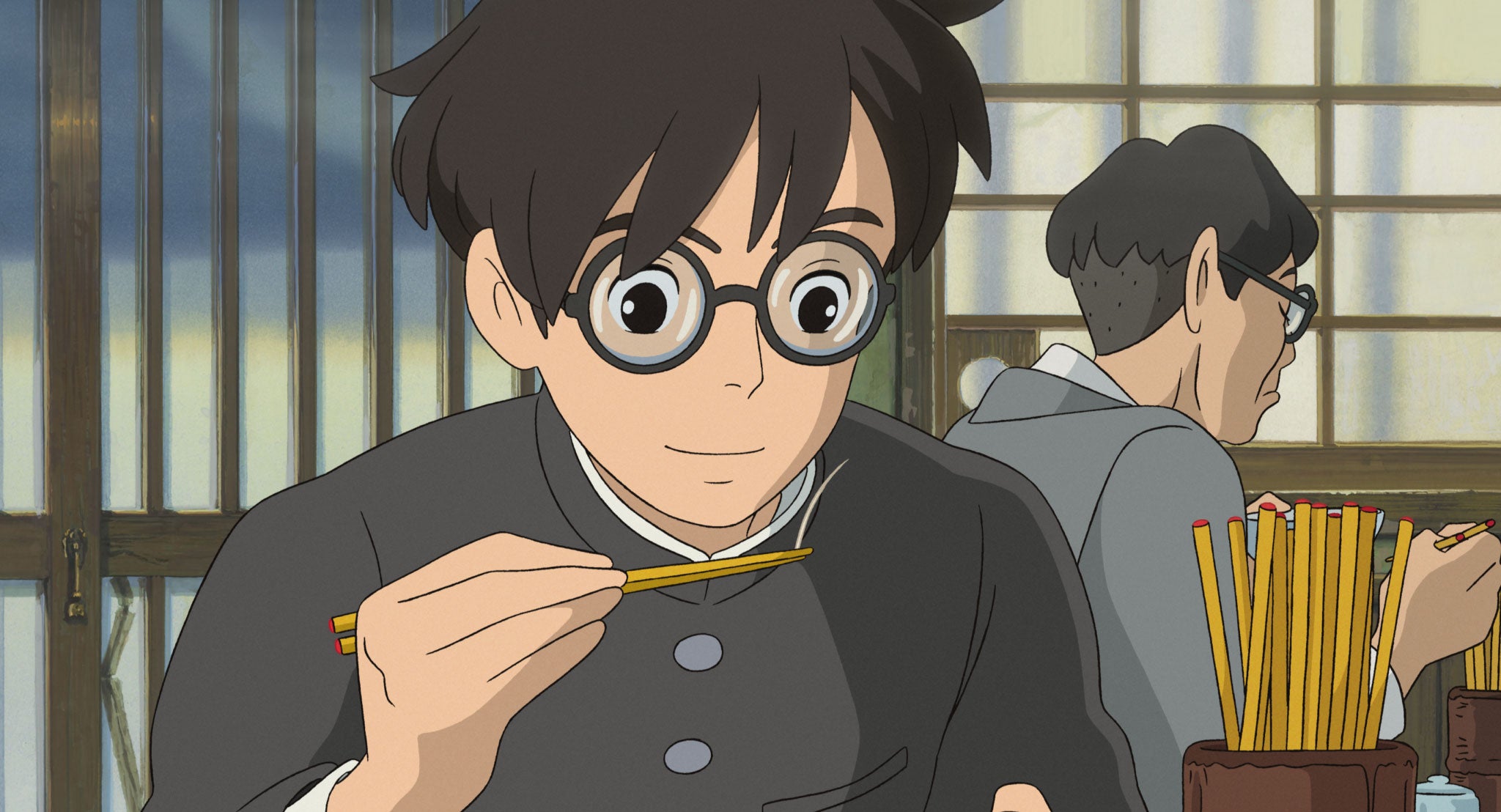

Miyazaki’s final film, The Wind Rises, has prompted some battles of its own. It received an Oscar nomination in this year’s Best Animated Feature category, but it has also stirred up controversy, both in Japan and abroad. Rooted more deeply in historical fact than most Studio Ghibli films, it’s a biopic of Jiro Horikoshi, the designer of the Mitsubishi Zero planes used in the raid on Pearl Harbour. Some critics have complained that Miyazaki’s tender reverie is too soft on Horikoshi; others have complained that it’s too hard.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Second World War aeronautics have always been close to Miyazaki’s heart. His father’s company manufactured rudders for Mitzubishi Zeros, and “Ghibli” was the nickname of the Caproni Ca.309, an Italian plane from the same period. A companion piece to Martin Scorsese’s Howard Hughes biopic, The Aviator, The Wind Rises is principally a love letter to an era when manned flight seemed impossibly magical and glamorous. But it’s also Miyazaki’s veiled autobiography, its hero being a man in thick-framed glasses who sits tirelessly at his drawing board, sketching things that have never been seen before.

For Wexler, the principal trait that Miyazaki and Horikoshi share is perseverance. “The common theme of all our films is the characters’ tenacity,” he adds. “They’re about facing challenges you weren’t expecting and finding reserves of strength you didn’t know you had. You certainly need that working in hand-drawn animation. It’s a long, long task. The Wind Rises was a product of at least five years’ work.”

That being the case, we can hardly blame Miyazaki for preferring to curate exhibitions and publish graphic novels from now on. But a Studio Ghibli with no new films from its creative visionary is unthinkable, isn’t it? “It is unthinkable,” says Wexler, “but it’s happened. We have two more films in production, and we have a library of films which we’re transferring to digital and putting out on blu-ray. But it’s a small studio, and the future is...”

Uncertain?

“‘Uncertain’ would be an appropriate adjective.”

The BFI ‘Studio Ghibli’ Season runs throughout April and May. ‘The Wind Rises’ is out on 9 May

Miyazaki's new release The Wind Rises

Greatest hits: Five of Miyazaki’s best

The Castle of Cagliostro, 1979

Miyazaki’s first feature film, released before Studio Ghibli was formed. A fast-paced, explosive tale of thieves, counterfeiters and assassins, with an evil count who resembles Terry Thomas and the first of many Miyazaki female leads who take charge.

My Neighbour Totoro, 1988

A fairytale elegy to the world of childhood and wonder, this parable of friendship owes much to Miyazaki’s fantastical imagination, especially in the giant, rabbit-like figure of Totoro, now the emblem of Studio Ghibli.

Porco Rosso, 1992

“I’d rather be a pig than a fascist” declares the hero of this highly original tale of a porcine seaplane fighter pilot that presages the rise of nationalist fervour in 1930s Italy and raises questions about reactionary societies and totalitarianism.

Howl’s Moving Castle, 2004

The plot – though solid, involving a young milliner who must seek help to reverse a curse – takes second place here to the flamboyant and capricious character of Howl, a wizard whose home chugs between dimensions, fired by a subdued demon flame. Wildly inventive and visually spectacular.

Spirited Away, 2001

Miyazaki’s most famous film is a nightmarish lament for the past, when spirits were respected. Filled with sustained menace, not least in the form of the ominous No-Face, it eulogises the importance of taking responsibility.

Robert Epstein

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments