Hail Caesar!'s Coen Brothers: their seven best closing scenes and what they mean

Ambiguous dreams, tornadoes and a narrating cowboy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With a new Coen Brothers film comes a new ending you'll be mulling over long after you leave the cinema.

While some may find themselves frustrated by sitting through a film only for its climax to offer no firm explanation as to what actually happened, these final scenes are a hallmark many would cite as a reason why they're fans of the directing duo.

As their new film Hail, Caesar! is released, we recount the Coens' best endings and attempt to offer some explanation as to what the hell they mean in the process.

Note: this is not a list of our favourite Coen Brother films, just their denouements.

7. Burn After Reading (2008)

What happens: The final scene sees two CIA types attempting to discern what it is that actually happened, surmising the film's sprawling events through one tongue-in-cheek monologue. "What did we learn?" one asks. "I guess we learned not to do it again," the other concludes, before saying: "I'm f*cked if I know what we did."

What does it mean: This ending infuriates and entertains viewers in equal measure; the film is a comedy of errors littered with inane and neurotic characters (John Malkovich's ex-CIA analyst Osbourne Cox and Brad Pitt's personal trainer Chad Feldheimer included) who bumble their way through the film, unaware they're all linked to each other through association.

The film's ending is known to lead to such exclamations as: "It can't end like that!" or "This film had no point!" These people would be wrong; the final scene accentuates everything that came before it - the CIA folk are ultimately just as bungling as the other characters ("I'll be f*cked to find out what we did" one says, the other responding: "Yes sir, it's hard to say."), no lessons were learned by anyone and similar events are certain to happen again. It's the zany Coen Brothers cycle - best get used to it.

6. The Big Lebowski

What happens? The Dude (Jeff Bridges) grabs a beer from the bowling alley bar he frequents and meets the story's narrating cowboy (Sam Elliott). When he leaves, the cowboy fills the audience in on what happens next. "Well, I hope you folks enjoyed yourself," he finishes. "Catch you later on down the trail."

What does it mean? The Big Lebowski is best encapsulated by this closing monologue, spoken by Sam Elliott's unnamed fourth wall-breaking cowboy. His narration, which sees him refer to the film's events (as well as those to come) highlight the kind nature possessed by The Dude ("It's good knowing he's out there, taking it easy for all us sinners," he says).

But what's its point? I'd argue the narration complements the notion that there's no necessity for every film protagonist to be a deeply-flawed multi-layered character seeking vengeance or self-enlightenment; they can simply be an abiding dude who moves through life without many cares in the world other than their rug. Do we need to be told that by a cowboy? The better question is: why not?

5. No Country for Old Men (2007)

What happens? Retired Sheriff Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) recounts two dreams to his wife: in one, he loses some money given to him by his father; in the other, he's riding on horseback through a snowy mountain pass, his father riding on ahead to set a fire "somewhere out there in all that dark ad all that cold... and I knew that whenever I got there, he'd be there," Bell says. "...and then I woke up." Cut to black.

What does it mean? The most enthralling aspect of No Country for Old Men's closing moments is that the Coen Brothers didn't write it. Instead, they adapted it from a Cormac McCarthy novel. Which isn't to say it's not staggering to behold just how in line this ending is with the Coen trope: a character monologue recounting an ambiguous dream - appropriately enough involving lost money (itself a Coen trademark); an unexpected cut to black before the film's loose ends are tied up - it's almost as if McCarthy wrote the 2005 novel in the hope brothers Coen would adapt it.

Personally, I believe the "he" Bell refers to at the end of his dream is not his father at all, but the malevolent killer Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) who we last see staggering away wounded from a car crash, hammering home the idea that danger lurks even when dormant.

4. Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)

What happens? It's 1961. As a young, unknown Bob Dylan takes to the stage in the Gaslight, Llewyn (Oscar Isaac) leaves and is beaten by the husband of a woman he heckled the previous night. As the man leaves, Llewyn shouts after him: "Au revoir."

What does it mean? The blindsiding thing about Inside Llewyn Davis' final scene is the realisation that you were watching something cryptic all along. As the film nears its end, the Coens show Davis reliving the same scenario we see play out as the film begins with a few changes. Firstly, he manages to keep the cat inside the apartment he's residing in having accidentally let the same cat out at the start (and consequently spending half the film locating it). Arriving at the Gaslight, Davis takes to the stage and performs, and, out in the alleyway, he gets attacked by the husband of the woman he's seen chiding earlier on in the film.

The question to ask, though, is whether the opening scene is a flash-forward. This theory would mean that the film you watch occurs after the final scene. Another common thought is that Davis is caught in some form of Groundhog Day-esque time cycle. My response to that is: if that's how you want to decipher it, fine - but I believe it to deeper than that. Llewyn is a character caught in his own cycle: he wants to succeed, he desires to possess an ambition, and yet he creates obstacles for himself over and over. He's not too dissimilar from The Graduate's Benjamin Braddock, who spends half of that film repeating aimless cycles. Davis will never get further than what we see - he'll never succeed - because he's refusing to let himself do so.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

A pessimistic notion, sure, but the signs of evolution are there. Will Davis prevail? Judging by Bob Dylan taking to the stage, probably not. Should he have broken out of his cycle would he have achieved the success earned by Dylan? Definitely.

3. Raising Arizona (1987)

What happens? Having returned Nathan Jr. - the baby they kidnapped - Hi (Nicolas Cage) and Ed (Holly Hunter) spend one final night together, their marriage on the rocks. Hi dreams of a bright future which culminates with the two sat at a dinner table - as an elderly couple - surrounded by children and grandchildren.

What does it mean? It's difficult to pinpoint what is so touching about the end of Raising Arizona: could it be how unexpected it's sentimentality is? This is, after all, a film following a couple committing one hell of a crime (kidnapping a baby due to their inability to conceive). Or could it be the futility at play? As Hi runs through his dreams - of how he and Ed remain an influence on Nathan Jr. without him realising it, "taking pride in his accomplishments as if he were our own;" spending a holiday in a house filled with a large family - he asks, "Was it wishful thinking? Was I just flinging reality like I know I'm liable to do?"

In retrospect, it's telling how the most futile outcomes of all the Coen Brothers' final scenes - the one that absolutely cannot come true - is the one we believe just may.

2. A Serious Man (2009)

What happens? As the doctor calls Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg) to discuss the results of a chest x-ray, a tornado bears down on his son Danny's (Aaron Wolff) school.

What does it mean? Only the Coen Brothers would end a film on the shot of a tornado looming large over a town. It may be easy to view this oncoming tornado approaching Danny's Minnesotan school as a metaphor symbolising the hurricane that'll be heaped upon Larry in the form of the inevitable bad news he'll hear from his doctor. But looking at the film's bigger picture and an existential cycle manifests. Just as The Dude will abide, Larry will face constant obstacles regardless of his actions (and just like his son will keep listening to Jefferson Airplane's "Somebody to Love" on repeat).

Perhaps this is why Larry relents, succumbing to the bribery presented to him by a student who wants to be marked up. Cue doctor's phone call and tornado; coincidental or karmic payback for poor Larry? That's your call to make. Either way, it's vaguely terrifying.

1. Barton Fink (1991)

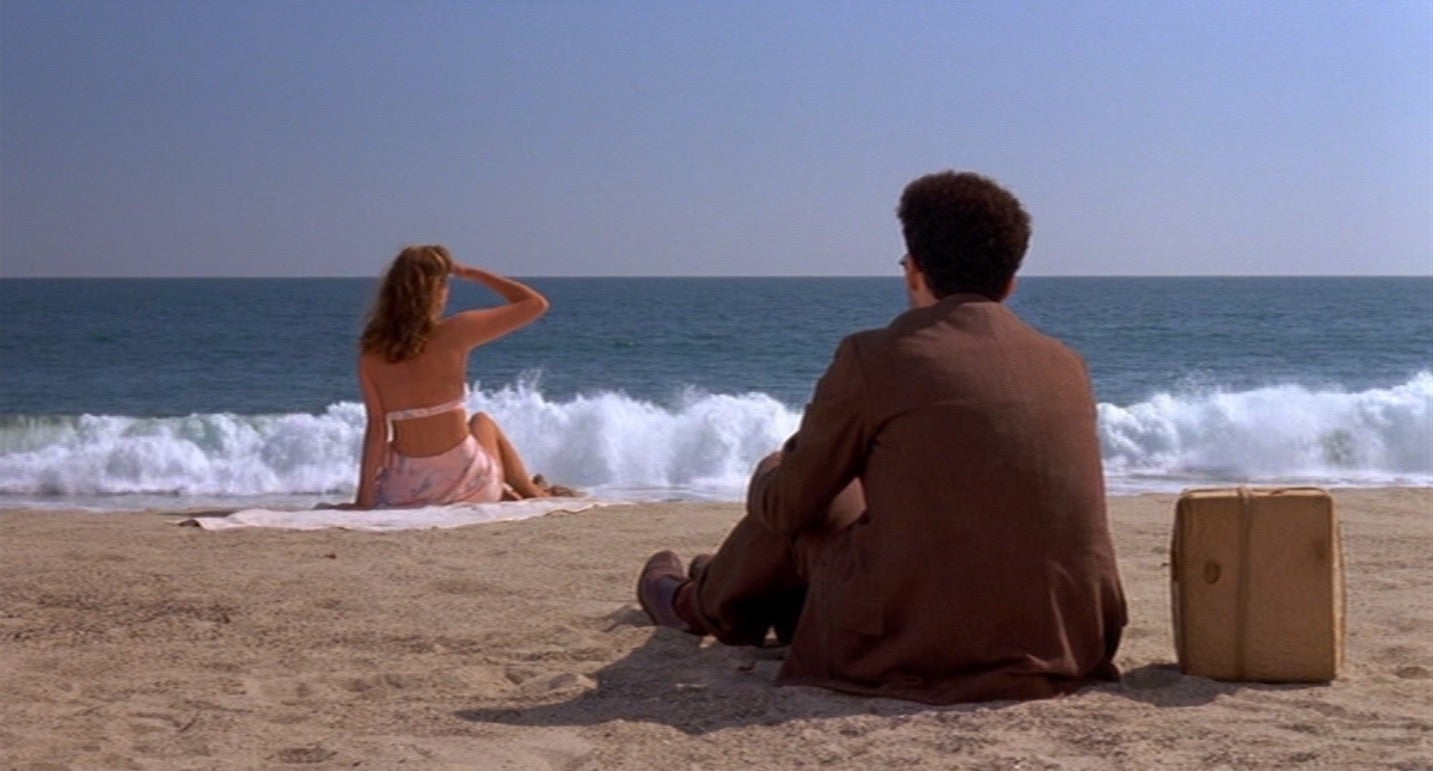

What happens? Barton Fink (John Turturro) wanders onto a beach holding a box filled with unknown contents. He meets a woman who sits down in front of him and assumes the exact pose of a photo seen throughout the film on his hotel room wall. "Are you in pictures?' he confusedly asks the unnamed woman as a seagull flies past and dies before dropping into the sea.

What does it mean? This ending reigns supreme for the sole reason that each time you watch it comes the ability to draw something new. The final shot being identical to the image depicted in the painting seen on the hotel room wall - a painting showed multiple times throughout - is not a subtle mirroring, but adopts a sense of eeriness. The fact this is the only time we see Fink away from his peers and outside the claustrophobic walls of the Hotel Earle should be freeing, however, the real-life depiction of the painting - life imitating art - pulls him right back; he's trapped, ensnared by the Hollywood system, heightened by the way he's signed into an inescapable contract with Capitol Pictures in the film's penultimate scene. Even the beach - a location associated with heat - harks back to the hotel, a place we see contains so much heat the wallpaper's are melting off the walls - hell, he's even content to carry around a box that doesn't belong to him, a sign of the weight he's being forced to bear.

The myth is that Joel Coen just happened to catch the bird dying while filming. It's clear as to why he opted to use this shot in the finished film though - it serves as an intriguing analogy for Fink himself: when we first see him, he's the toast of the play world, his career soaring; when he agrees to go to Hollywood, said career draws to an abrupt halt, more than likely causing the downfall of Fink's career.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments