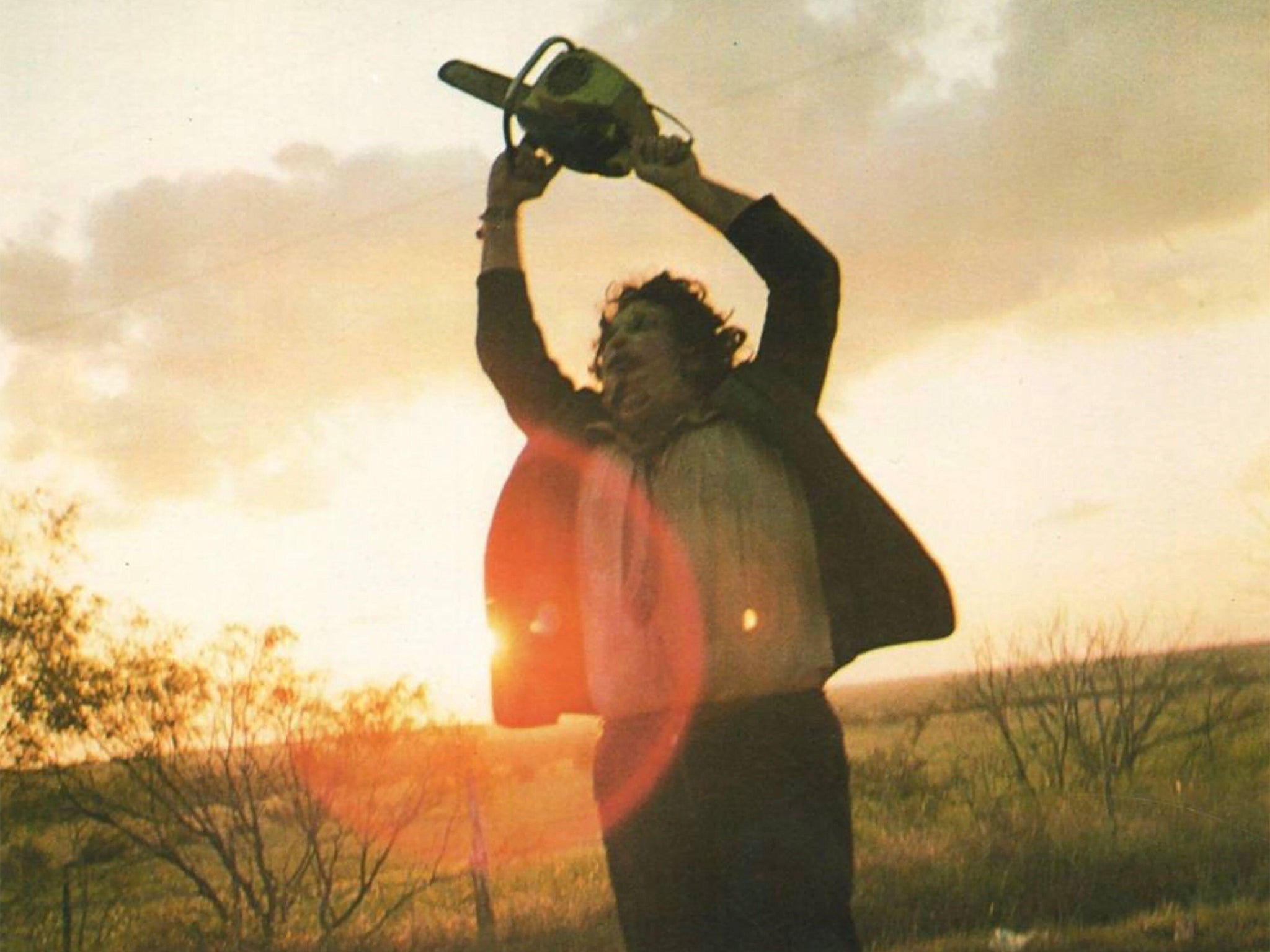

The long shadow of ‘The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’ looms over the horror genre

It’s a rare movie that learns the lessons of ‘The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’, what that film did was unique, but Ti West has come close with ‘X’, writes Jason Zinoman

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fifteen years ago, I sat down with 20 or so of the most prolific serial killers in the world, responsible for hundreds of stabbings, decapitations and other unspeakable murders – and was absolutely charmed. A get-together of directors of scary movies, including Wes Craven, Eli Roth, Larry Cohen, Don Coscarelli and Robert Rodriguez, this event, semi-jokingly referred to as “the masters of horror dinner,” was giddily jovial. Just as comedians tend to be more serious in person than you expect, horror artists are, generally speaking, very funny.

The one time I recall the mood turning solemn was when discussion shifted to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). With its director, Tobe Hooper, shyly nibbling on his salad, everyone took turns describing the first time they watched this unlikely masterpiece. They spoke in vivid, awestruck detail, as if recalling a religious epiphany.

Of the classic horror movies of its era, none is more revered among genre filmmakers. Yet Chain Saw has been stubbornly hard to imitate in comparison with peers like Night of the Living Dead and Halloween, which spawned entire genres. You can detect the influence of Chain Saw, however, in a spate of recent movies, including Ti West’s X, a thrilling new indie from A24 that captures the disreputable pleasures of 1970s horror with slickly modern refinement.

The peculiar strengths of Chain Saw have rarely been replicated because they are often misunderstood. Despite its unsubtle title, this is a formally exquisite art film, packed full of gorgeously nightmarish images, as poetic as they are deranged. The movie is less bloody than its reputation. While every bit as intense as its title, its violence is staged with misdirection absent from the sequels and remakes.

Another misperception, internalised even by experienced and admiring critics, involves its most famous character, Leatherface. In a Variety review last year, Owen Gleiberman drew the ire of horror fans when he called Halloween a “knockoff” of Chain Saw, then defended his stance in an essay locating the signature of both movies in the killer’s mask. “It expresses his identity,” he writes of Leatherface, “and his identity is that he has no identity.”

Gleiberman was on solid ground with Halloween, whose killer is a psychologyless abstraction, murdering without motivation, but Leatherface is more than just a boogeyman. While he is introduced committing some of the most startling kills in cinematic history, the majestically maniacal last act of Chain Saw shifts our perspective on him from hulking slayer to stammering stooge. Without resorting to a tedious backstory, the movie positions Leatherface as a monster and a victim, bullied into his dirty work by his cannibalistic family. He is closer to the misunderstood creature from Frankenstein than to a garden-variety slasher villain.

At a time when the reputation of scary movies was much lower, pornography was being taken seriously. This is the cultural backdrop of ‘X’ – but also in part its subject

The feat of Chain Saw is to make us empathise with its scariest figure without diminishing the disorienting, teeth-chattering horror. Few movies pull this off.

The best movies made in the spirit of Chain Saw grasp that the source of its deepest madness is the family dynamics. Rob Zombie’s gnarly Firefly trilogy (House of 1000 Corpses, The Devils’ Rejects, 3 From Hell) and the original and remake of The Hills Have Eyes (both terrific) capture the relatable dread of a dysfunctional family, taken to a Grand Guignol extreme.

West’s X centres on a confrontation with a disturbed rural family in 1970s Texas, an elderly couple who appear creepy and hostile, before their vulnerabilities are exposed and they also become poignant. The film’s kinship with Chain Saw is most obvious in its stunning visual vocabulary: the ominously vast blue sky, a strobe-light editing sequence, a long view of a screen door from inside a creaky house. There is the dread evoked by rusty tools and wrinkly skin – and even an echo of the scene of Leatherface doing a balletic spin.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

His sitting ducks are making a low-budget pornographic movie inspired by the success of Debbie Does Dallas. It helps to know that Chain Saw was made by a seedy New York company, Bryanston Distributing, that was flush from the success of the famous sex film Deep Throat. The line between horror and porn was blurry in the 1970s. They shared some of the same artists, audiences and grimy theatres. At a time when the reputation of scary movies was much lower, pornography was being taken seriously. This is the cultural backdrop of X but also in part its subject, and the film keeps searching for the intersection between sex and violence. In one pointed sequence, West juxtaposes a scene of staged seduction with one of real menace, underlining the echoing tension.

Whereas Texas Chain Saw was about economic displacement (new technology cost Leatherface and his family their jobs at the slaughterhouse), X is about sexual displacement, how the old inevitably gives way to the young. The resentment this inspires is the fuel of the horror, which the victims don’t see coming. They are too busy trying to become famous making a film. The young, idealistic director of the sex picture just wants to make a “good dirty movie,” but tensions rise when his girlfriend tries to join the cast. He refuses, saying, disingenuously, that he can’t change the script. She counters that audiences care less about plot than about sex, asking, “Why not give the people what they’re paying for?”

Even if West identifies with the director, he doesn’t give him the better argument.

After making a series of elegant, slow-burn scary films like The Innkeepers and The House of the Devil, which earned critical praise if not blockbuster grosses, West has now made a movie full of flamboyantly gory kills and leering sex scenes. You might say he finally gives the horror crowd what they’re paying for. But instead of compromising his aesthetic, indulging in the traditional muck of the genre actually loosens and expands that aesthetic. His movies have long paid homage to the delirious bloodbaths of the grind house era. But this is his first that feels like one.

Horror has always been about repressed pleasures. Like comedy, it also depends on the shock of the unexpected. Chain Saw is a disreputable exploitation flick made with such artistry that it transforms into high art. X arrives in a different context, an era of so-called elevated horror and the kind of respectability that should make any gore-hound nervous. So West has reversed the trick. He made an A24 production with the spirit of a B movie.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments