Terry Gilliam: ‘I’m tired of white men being blamed for everything wrong with the world’

After two decades of trying, the director and former Monty Python member has finally managed to make ‘The Man Who Killed Don Quixote’. But he’d rather talk to Alexandra Pollard about #MeToo, the trials of being a white man, and why he’s decided to become a ‘black lesbian in transition’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.By his own admission, Terry Gilliam is offensive. But it’s not his fault, it’s yours. “People work so hard to be offended now,” he says with a grin. “I don’t know why I’m doing it. It’s not fun anymore.” He seems to be enjoying himself today, though. The more incendiary his opinion – that the #MeToo movement is a witch hunt; that white men are the real victims; that actually, it’s women who hold all the power – the bigger that smile.

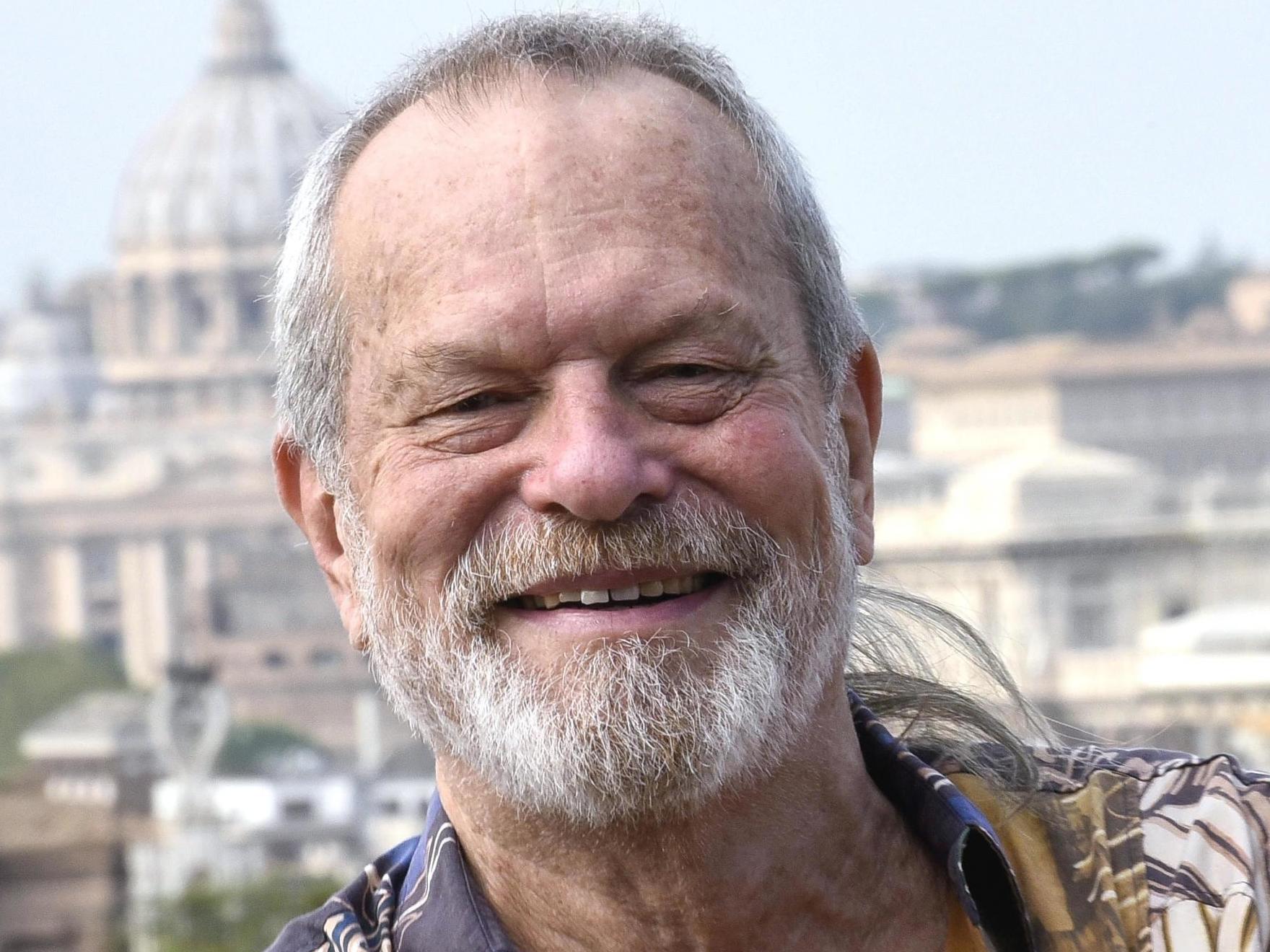

We’re in an office suite in central London to discuss Gilliam’s new film, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. But the 79-year-old writer, director and former Monty Python member has other ideas. “I’m so booored of talking about the film,” he groans, rolling up the sleeves of a maroon overshirt, which has a cut not dissimilar to a posh dressing gown. With grey hair, cut short except for a long rat’s tail around the back, and a weathered face, he looks his age – just about – but he has sharp, keen eyes, and the air, energy and trainers of a man many years younger.

You’d think, given that he’s been trying to make his magical-realist adaptation of Cervantes’ 1605 novel for nearly two decades, he’d be itching to talk about it. The film’s journey to completion has been so troubled – there were lawsuits, funding failures, collapsed distribution deals and natural disasters – that a documentary was made about it in 2002. Gilliam even started filming back in 2000, with Johnny Depp and Jean Rochefort in the lead roles, but production was abandoned on day two when a flood wiped out the set and Rochefort’s back went into spasm.

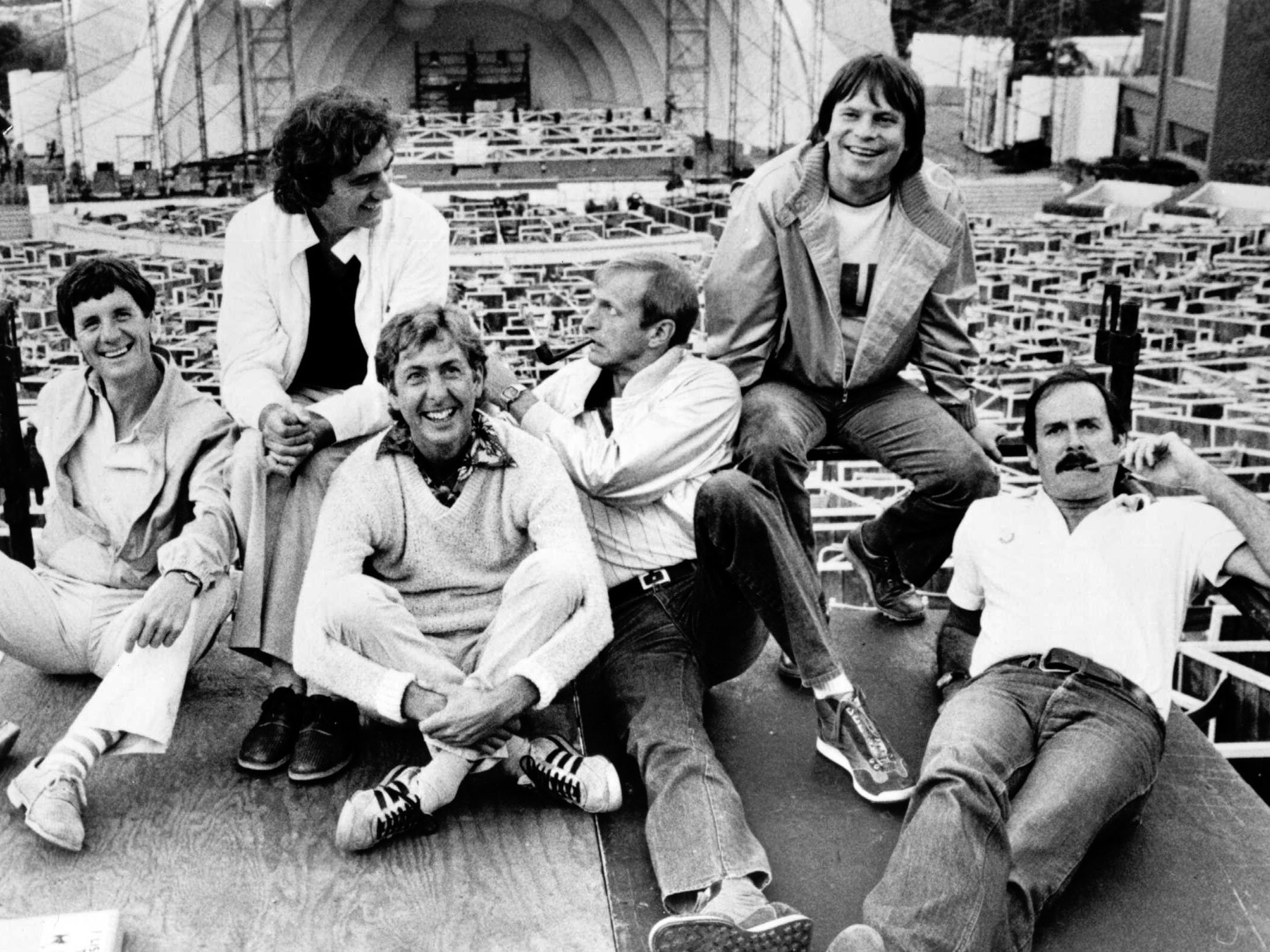

He’s had other setbacks in the meantime. Heath Ledger, the star of his 2009 film The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, died midway through filming, and was replaced by a handful of A-listers. And his 2013 sci-fi film The Zero Theorem flopped spectacularly. But his early years were an embarrassment of riches. After starting out as an animator for Monty Python – he’s responsible for those surreal, Dali-esque collages and that famous giant foot – Gilliam soon joined the troupe full time, the only American-born member among five Brits. His directorial debut was with them, 1975’s riotous Monty Python and the Holy Grail, and he helped write the equally adored (though not by Catholics) Life of Brian (1979).

And when the Pythons slithered their separate ways, he kept on going, making work that was weird and fantastical, shot through with dark comedy and dystopian undertones: 12 Monkeys (1995) with Brad Pitt, for example, and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) with Johnny Depp. But his masterpiece is surely 1985’s Brazil, an Orwellian dystopian satire starring Jonathan Pryce as Sam Lowry, a low-level government worker trying to find the woman of his dreams (literally).

Gilliam’s teamed up with Pryce again for The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, which finally got off the ground thanks to a large cash injection – which he says came from a woman who identified with “my jihad, mein kampf”. It is a beguiling film. Pryce plays Javier, an elderly man who believes himself to be Don Quixote. And Adam Driver is Toby, an arrogant advertising director who triggered Javier’s delusion by casting him in his student film a decade ago. “Don Quixote is a mad man,” says Gilliam, who has reluctantly deigned to talk about the film for a moment, “but his view of the world is a noble one. It’s about chivalry. It’s about rescuing maidens. All these wonderful ideas.” The film flits between the 17th century and the 21st. Is it about the clash between modern masculinity and old-fashioned ideals of manhood?

“There’s no room for modern masculinity, I’m told,” says Gilliam. “‘The male gaze is over,’” he adds, letting his derisive air quotes hover for a moment. He was trying to make a point with Angelica, though. Played by Joana Ribeiro, Angelica is a young woman who was in Toby’s film when she was 15. He told her she could be a star, but hasn’t spoken to her in the years since, and her attempts to make good on his prediction have failed. Now, she works as a model and an escort.

“In the age of #MeToo, here’s a girl who takes responsibility for her state,” says Gilliam. “Whatever happened in this character’s life, she’s not accusing anybody. We’re living in a time where there’s always somebody responsible for your failures, and I don’t like this. I want people to take responsibility and not just constantly point a finger at somebody else, saying, ‘You’ve ruined my life.’”

The day we meet, Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein – who’s been accused by dozens of women of rape, assault and sexual harassment, allegations that kickstarted the entire #MeToo movement – broke his silence, to lament the fact that his work “has been forgotten”, and to boast that he is a “pioneer” of female-led films. Isn’t it a bigger problem that men are refusing to take responsibility for abusing women, and abusing their power? “No. When you have power, you don’t take responsibility for abusing others. You enjoy the power. That’s the way it works in reality.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

And then that phrase comes up. Witch hunt. “Yeah, I said #MeToo is a witch hunt,” he says. There’s a silence. “I really feel there were a lot of people, decent people, or mildly irritating people, who were getting hammered. That’s wrong. I don’t like mob mentality. These were ambitious adults.”

“There are many victims in Harvey’s life,” he adds, “and I feel sympathy for them, but then, Hollywood is full of very ambitious people who are adults and they make choices. We all make choices, and I could tell you who did make the choice and who didn’t. I hate Harvey. I had to work with him and I know the abuse, but I don’t want people saying that all men… Because on [the 1991 film] Fisher King, two producers were women. One was a really good producer, and the other was a neurotic bitch. It wasn’t about their sex. It was about the position of power and how people use it.”

Being neurotic and being an alleged rapist are not the same thing, though. Many women have made very legitimate accusations against many powerful men. “And those are true. But the idea that this is such an important subject you cannot find anything humorous about it? Wrong!”

Gilliam mentions a famous actor he was speaking to recently. “She has got her story of being in the room and talking her way out. She says, ‘I can tell you all the girls who didn’t, and I know who they are and I know the bumps in their careers.’ The point is, you make choices. I can tell you about a very well-known actress coming up to me and saying, ‘What do I have to do to get in your film, Terry?’ I don’t understand why people behave as if this hasn’t been going on as long as there’ve been powerful people. I understand that men have had more power longer, but I’m tired, as a white male, of being blamed for everything that is wrong with the world.” He holds up his hands. “I didn’t do it!”

It is deeply frustrating to argue with Gilliam. He is both the devil and his advocate. I try to say that it’s not that white men are to blame for everything, but that they are born with certain privileges that, too often, they exploit. He interrupts.

“It’s been so simplified is what I don’t like. When I announce that I’m a black lesbian in transition, people take offence at that. Why?”

Because you’re not.

“Why am I not? How are you saying that I’m not?”

Are you?

“You’ve judged me and decided that I was making a joke.”

You can’t identify as black, though.

“OK, here it is. Go on Google. Type in the name Gilliam. Watch what comes up.”

What’s going to come up?

“The majority are black people. So maybe I’m half black. I just don’t look it.”

But earlier, he described himself as a white male.

“I don’t like the term black or white. I’m now referring to myself as a melanin-light male. I can’t stand the simplistic, tribalistic behaviour that we’re going through at the moment.” He smiles. “I’m getting myself in deeper water, so I have to trust you.” I’m not sure what he’s trusting me to do.

“I’m talking about being a man accused of all the wrong in the world because I’m white-skinned. So I better not be a man. I better not be white. OK, since I don’t find men sexually attractive, I’ve got to be a lesbian. What else can I be? I like girls. These are just logical steps.” They don’t seem logical. “I’m just trying to make you start thinking. You see, this is the world I grew up in, and with Python, we could do this stuff, and we weren’t offending people. We were giving people a lot of laughter.”

He’s right about that. But at its best, Python was silly and whimsical, its more pointed satirical moments punching up, not down. At its worst, it missed the mark, objectifying women when it wasn’t depicting them as shrill and preposterous, and using racial slurs that would rightly horrify people today. Gilliam doesn’t see the difference.

“I’m into diversity more than anybody,” he says, “but diversity in the way you think about the world, which means you can hate what I just said. That’s fine! No problem. I mean, you can believe whatever you want to believe, but fundamentalism always ends up being, ‘You have to attack other people who are not like you,’ and that’s what makes me crazy. Life is fantastic, it’s wonderful, it’s so complex. Enjoy it and play with it and have fun. That’s why I didn’t become a missionary. That was my plan. I was quite the little zealot when I was young, but when their God couldn’t take a joke, I thought, ‘This is stupid.’ Who would want to believe in a God that can’t laugh?”

The publicist comes back into the room to tell us our time is up. “We didn’t talk about the film even once!” he tells her, with the glee of a schoolboy telling on his classmate. I get up to leave. “I don’t know how you got stuck with me in this mood,” he says. “I just love arguing. And if you’ve got a point, you should be able to argue your thing.” That grin is back. “But I’m not going to hit you.”

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote previews nationwide on 23rd January with Terry Gilliam Q&A and is in cinemas from 31st January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments