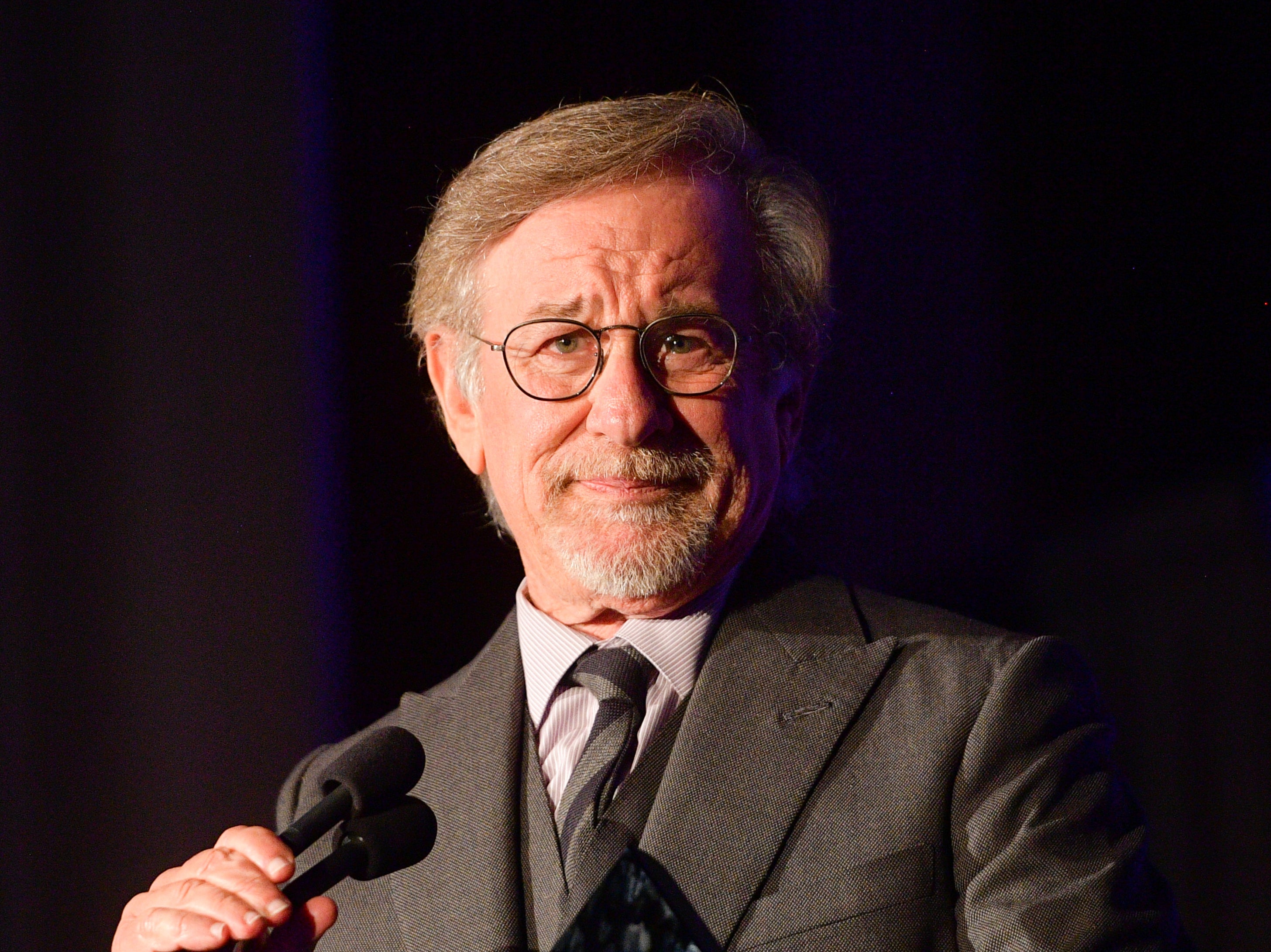

Steven Spielberg deserves better than to be treated as cinema’s fusty grandfather

Nostalgic, sentimental and yawningly moral or bold, innovative and untouchable? As the director who created the modern blockbuster treats the world to ‘West Side Story’ – his first ever musical – Louis Chilton asks whether Spielberg has anything left to prove

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You’d think it would be sacrilege to badmouth Steven Spielberg. As filmmakers go, the 74-year-old is a monolith, his very name synonymous with cinema itself. After inventing the modern blockbuster with Jaws in 1975, Spielberg went on to create a number of the biggest films ever made. Saving Private Ryan completely redefined the war movie; Jurassic Park was pioneering in its use of CGI. Even the worthiest heirs dubbed “the new Spielberg” (like Christopher Nolan or Denis Villeneuve) seem ghostly pale by comparison. And yet: as cinema’s populist maestro enters the sixth decade of his career, it’s hard not to notice that some people equate Spielberg with everything they don’t like about movies.

Spielberg has always been in thrall to a certain set of compulsions. He’s sentimental. He’s nostalgic. He’s moral, sometimes verging on didactic. While there are a few gems among his recent films, few would argue the last decade and a half holds a candle to his original mid-1970s-to-early-1980s run, or his mid-Nineties-to-early-Noughties resurgence. Some movies – such as The BFG, or Ready Player One – have been complete misfires. Spielberg has often made the odd dud among the pearls (1941, anyone?) but now there is no Raiders to act as a counterweight, no crossover critical and popular hits that silence all doubters. His recent successes have been more subdued, mid-budget adult dramas, films like War Horse, Lincoln, Bridge of Spies or The Post. They are by no means bad, but simply handsome and old-fashioned: middlebrow flicks to be chewed over, rather than marvelled at. When he was coming up, as part of the New Hollywood movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Spielberg was a disruptor, an underdog; now, he’s firmly part of the establishment. The problem is not that Spielberg has suddenly lost his ability to make movies, but that he risks being seen, by younger viewers especially, as cinema’s fusty grandfather.

Films website Taste of Cinema placed him on a list of the most “overrated” directors, characterising works like Lincoln as “long and sterile”. Other criticisms have focused on his apparently unfailing faith in American idealism. In a damning review of The Post, Little White Lies’s Charles Bramesco wrote that the film’s ultimate undoing was “Spielberg’s attachment to an America that no longer exists”. At a glance, Spielberg’s latest project, an adaptation of the Leonard Bernstein/Stephen Sondheim musical West Side Story, seems to indulge all his strongest nostalgic instincts. A 64-year-old musical is never going to revolutionise cinema the way Jurassic Park did. But maybe a story about young love, crime and the American immigrant experience is just the thing to prove that Spielberg can still speak to the younger generations the way he used to.

After all, it’s only in the past decade or so that Spielberg’s reputation as a buttoned-down traditionalist has really taken hold. Many of his New Hollywood cohorts have escaped this fate, either through dying, receding from the spotlight (like Brian De Palma or Francis Ford Coppola) or otherwise retaining some sense of countercultural “cool”, like Martin Scorsese. The fact is, Spielberg has stared down doubters all his life. After hitting it big with swashbuckling blockbusters such as Jaws, Raiders of the Lost Ark and ET, he was accused by sceptics of lacking depth. So he attacked drastically weightier projects, emphatically adult-oriented films such as The Color Purple, Schindler’s List (which won him his first Oscar) and Amistad. In 2001, the cold thriller Minority Report and the soul-crushingly bleak sci-fi AI: Artificial Intelligence seemed to vehemently refute the accusation that he was too sentimental. As Spielberg entered the 2000s, with two Best Director Oscars under his belt (and a Best Picture win for Schindler’s List), he was no longer simply the blockbuster king. But he hadn’t abandoned mass-market entertainment, as films like Catch Me If You Can, War of the Worlds and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull showed.

It doesn’t help that some of Spielberg’s favoured collaborators in recent years have suffered similar pigeonholing. Tom Hanks, for instance, has appeared in five Spielberg films, including Bridge of Spies and The Post. Like Spielberg, Hanks is an undeniable giant in his field, but often regarded as lacking edge, a little too nice. John Williams, Spielberg’s go-to composer for decades, is another whose elite artistry is sometimes taken for granted; his terrific scores to films such as The Post and Lincoln have been dismissed by some for the same reasons that Spielberg has. They’re too classical. Too sentimental. Old hat. Is this just ageism, on some level? Over-familiarity? Or have their own standards simply been set too high?

Even if we were to accept that some of Spielberg’s recent efforts lack the timeless power of Jaws, it’s just incorrect to suggest that he’s settled into a rut of action-less adult dramas. Over the past decade, he has experimented with animation (in the surprisingly great Adventures of Tintin), children’s fantasy (The BFG) and internet-era sci-fi (Ready Player One). The latter was rightly regarded as one of his worst films, but there’s still an irrefutable level of craft to many of the action scenes.

What Ready Player One showed, at least, is that Spielberg is still willing to take risks, even if they don’t pay off. That’s the thing about West Side Story. The muted sense of excitement over the past two years has belied just how daring a choice it really is. Spielberg has never made a musical before; most modern big-name directors won’t touch them with a barge pole. He has taken on the project knowing full well how tall the shadow of the 1961 original looms, knowing that anything short of greatness would be a rank disappointment.

Between West Side Story and the forthcoming semi-autobiographical film The Fabelmans, you can expect to hear a lot of Spielberg’s name over the next couple of years, especially when it comes to Oscar season. If anyone deserves another spin around the golden carousel, it’s Spielberg, an outsider who forced his way in by rebuilding the entire industry in his image. It doesn’t matter if he’s not making ’em like he used to. Neither is anyone else.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments