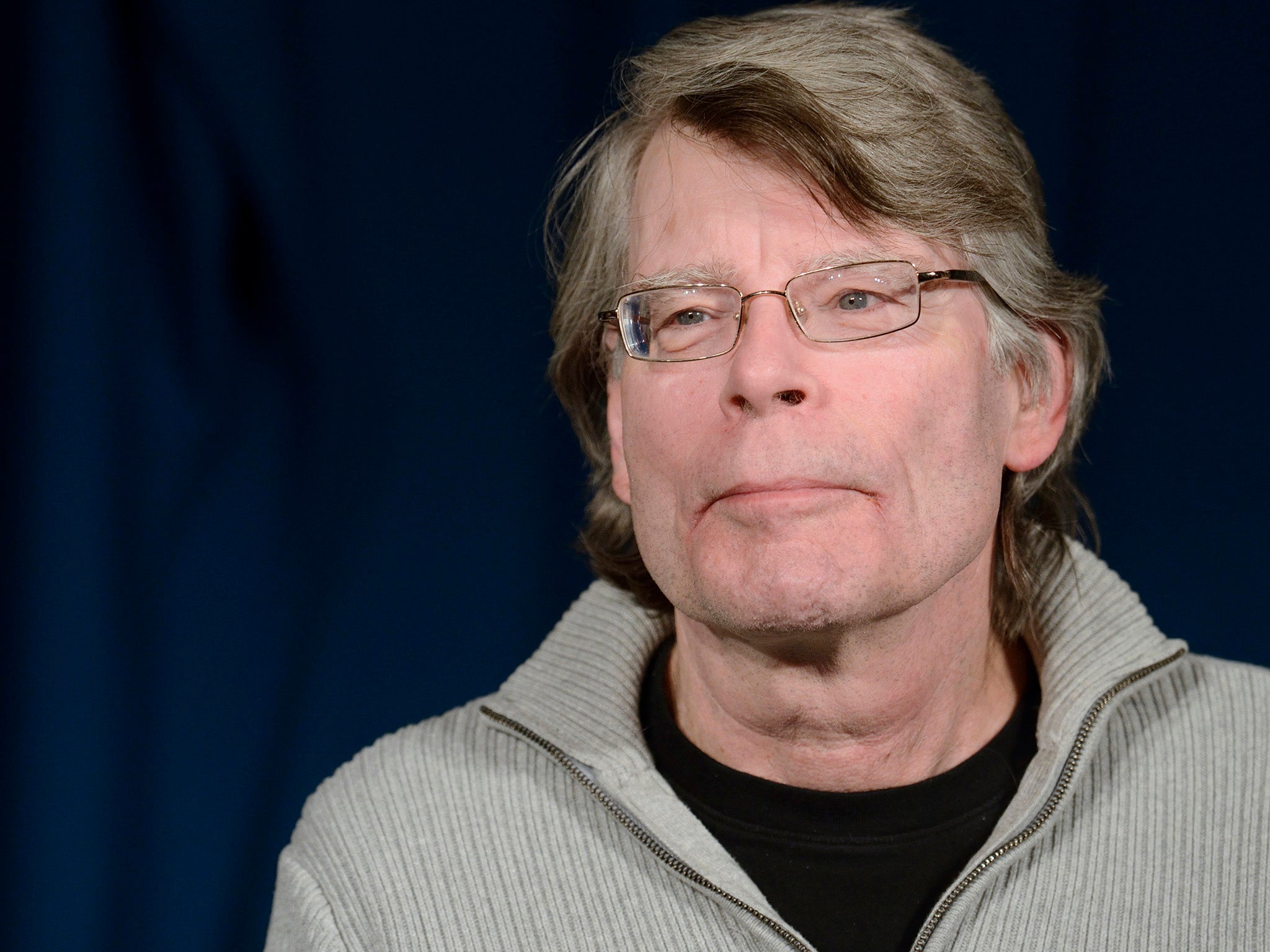

America’s dark Disney: How Stephen King conquered the screen

The BFI Southbank’s ‘Stephen King On Screen’ season has only managed to fit in half of the 44 King films which include ‘The Shining’, ‘Carrie’ and ‘The Shawshank Redemption’ – and that is not including sequels, remakes and TV adaptations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Stephen King is a cinematic source like no writer before him. A new BFI Southbank season of his work ranges from four boys coming of age in Stand By Me to the girl who apocalyptically ends her adolescence in Carrie. The Shawshank Redemption is pure concentrated storytelling in a prison’s confines, The Mist a dismantling of human nature in a besieged hardware store. Misery and The Dark Half investigate authorial identity, while The Dead Zone’s premonition of a dangerous populist President crashes into Christine’s killer car. The most prestigious adaptation to be screened, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, is an ice sculpture of a film which freezes its source novel’s heart.

The season finds room for less than half of the 44 King films (excluding sequels and remakes), or the swelling number of TV adaptations (at least 28, some several series long). Between them, they have helped define King’s reputation as a writer, while often baulking at his bleakest qualities. They’re a sub-genre all their own, rooted, like King himself, in small-town America, and provincial, private horrors. At times, King films’ sheer, overwhelming volume has sucked the life from their rivals, and become American horror.

“Apart from Shakespeare, there aren’t any writers who have every bit of their work adapted to the screen, and he’s well on the way to that,” Gabriella Apicella, a screenwriter who will discuss King’s work during the season, argues. “The 20 stories in the season have all come from the same brain, and been turned into successful films, and it almost demands a genre. Purely because there’s so much work, it’s created a niche, with imitators who haven’t matched his style.

“There are conventions and stylistic choices that he makes in his work that tap into a very core sense of the human psyche,” Apicella explains. “You’re willing to go into this crazy paranormal stuff, because at the heart of it is something we’ve all experienced, whether it’s coming of age, or financial hardship. He’s brave enough to unpack what frightens us in the most extensive and imaginative way.” For Apicella, Pet Sematary, a notorious 1983 King novel directed by Mary Lambert from his screenplay in 1989, in which a family cat is horribly resurrected, and then a child, sums up his extreme strengths. “Pet Sematary really got me,” she shudders, “because it’s that primal thing of the death of a loved one, and all the horrible guilt associated with that. And it makes sense. Of course you would be tempted to try this resurrection thing, if it’s there in your back garden. It’s hideous and disgusting, but of course you would. King doesn’t shy away from that. He delves into it.”

King’s co-producer on the recent TV adaptation of his novel Under the Dome, Steven Spielberg, makes for an instructive comparison. While Spielberg was dubbed the new Disney in the 1980s, King has matched him as America’s great storyteller of the baby-boom era, and the two are more similar than is generally realised. Spielberg made his reputation with two ruthless monster movies, Duel (1971) and Jaws (1975), with a TV movie about a possessed child, Something Evil, in between. In his 1981 book Danse Macabre, King found Duel “almost painfully suspenseful”, also approving “the little kid’s torn and bloodstained rubber float nudging against the shoreline in Jaws”.

Both men are 70 this year, and grew up far from America’s hip cultural centres: King in small-town Maine, Spielberg in the suburbs of New Jersey, Ohio and Arizona, and small-town Saratoga. Both connected to vast Middle American audiences long before the coastal intelligentsia acknowledged them (in 1982, Time named King “The Master of Post-Literate Prose”; in 2003, the National Book Foundation gave him its Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters). Both became full-blown phenomena when they dominated 1980s cinema screens, even if King had no say in adaptations which often languished in B-movie slots, such as 1984’s atmospheric, puffed-up short story The Children of the Corn. “This thing could be made for a quarter,” that film’s producer recalled of the low-rent MO which stopped Sam Raimi directing it, “and shot in a week in a cornfield.”

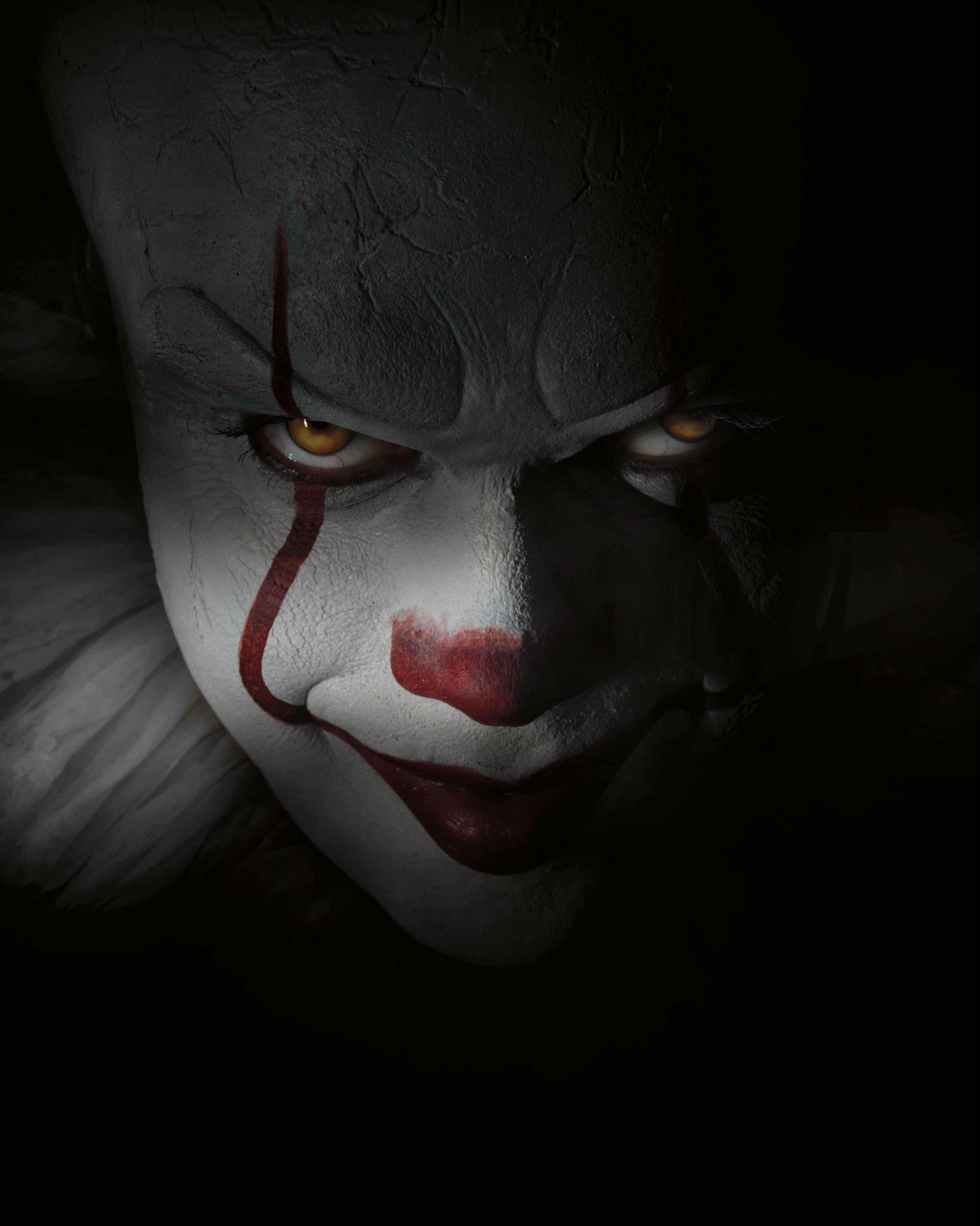

Spielberg struggled for longer than King to convincingly portray adult emotions. But both found an emotional wellspring in the long hot summers of American childhood and adolescence. King’s deeply autobiographical novella The Body was adapted by Rob Reiner as Stand By Me (1986), but both could be by Spielberg. So could The Shawshank Redemption. There’s a slug-filled corpse in The Body, while King’s IT has not just a clown-faced murderer of children, but a child who makes another child eat dog-shit. Still, it’s all Americana. If Spielberg is one new Disney, King has been his dark twin.

The British director Johannes Roberts has just adapted another King novella with that Stand By Me pang for the past, Hearts In Atlantis, the title story of a collection which is the writer’s defining statement on the 1960s. Roberts feels such emotional resonance is often crucial to King’s appeal. “The story’s about a group of poor, scholarship kids at university, who have to keep up their points average to avoid the Vietnam draft,” he explains. “What attracted me to it is King’s way with the moment in time. It’s a nostalgic coming of age story, about this group of people thrown together in this little bubble, and King does it so well. What Hearts In Atlantis does is almost like what The Breakfast Club does. It’s about that certain night, or months, that are really amazing. And then that moment is gone.”

Roberts had to find his own solution to one of the paradoxes of King’s success. For all the narrative drive you feel reading his fiction, when you lay that story out, it’s often more discursive and less cinematic than it looks, set in the narrator’s head, and pulled along by their voice. “It is tricky,” Roberts agrees, “they are all in the characters’ head, and you have to work out a way of bringing King’s voice to the screen. The way I’ve done it is the way Shawshank did it, and Stand By Me to an extent, by keeping as much of the prose as possible in voiceover. But there are different ways. Carrie is a great example of taking the book and turning it into pure cinema.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Does Roberts think King is genuinely cinematic? The resultant filmography is after all rather like Michael Caine’s, with much dross to pan through for the gold.

“People say a lot of the movies aren’t successful,” Roberts counters. “But Shawshank, Stand By Me, Pet Sematary, Carrie, The Shining, Christine, Cujo, The Green Mile, Dolores Claiborne - if one filmmaker had done all of those movies, that would be an insanely amazing CV. Most of the dogs tend to be the short stories, where you have the spring-point of King’s imagination, but he kept it to the short story because it didn’t have what it needed for a full arc. And then you try and put a full world in it like Children of the Corn, and it doesn’t work. The Night Flier is the only exception [this little-seen, 1997 shot of black-hearted pulp about a tabloid journalist hunting a vampire through small, misty Midwestern airports is included in the BFI season].”

Apicella believes King’s individual scenes are intensely cinematic. “You can see camera movements, and almost the hear music,” she says. “There is a real visual world-building that he does.” She concedes that the scale of King’s often capacious work is a daunting challenge for directors, and that director Andy Muschietti should get “a massive badge of bravery” for his upcoming IT adaptation. “IT is 1,000 pages. It’s so much more than the pop culture thing of scary clowns. But they’re making it in two films, with the characters as kids and then as adults, which makes much more sense.”

Apicella thinks the secret to successfully adapting King anyway lies in heart, not horror. “King’s a traditionalist, in that story and character is everything. I don’t blame him for not being a fan of the Kubrick film of The Shining, because the book is so much more complex and nuanced, about someone you can really root for in his distress and pain as he unravels, and becomes this brutalised monster who terrorises his family. And in Misery, when Annie Wilkes makes the author burn his manuscript, the real psychological torture isn’t depicted as much in the film, because that stuff takes time, like reading does. If a film takes character and narrative at its core, it succeeds. That’s not necessarily so attractive to producers who expect big scares and action, where King’s perceived success is. But his real success is in the human side.”

“What TV has to sell more than entertainment, more than anything else, is time,” King himself said, reflecting on Under the Dome’s great US success. “It gives you the time to tell a story in depth.” After decades of mediocre TV adaptations (which CBS’s Under the Dome isn’t much better than), this is the new boomtown for screen King. Non-network TV’s creative openness now goes far beyond Hollywood, as shown by the current series adapting King’s crime novel Mr. Mercedes. A scene in which its young mass-murderer is kissed hard by his drunken mother, then spins into the basement to masturbate his confusion away, finds an adaptation finally going as disturbingly far as King does. An episode mostly spent watching Brendan Gleeson’s ex-policeman hero gloomily mooch around his house also allows an interiority much like the books. “It’s very difficult to show monotony or just be with characters in a film, because it’s lost screen time,” says Apicella. “But in TV, you can increase the pressure over a much longer period, while digging into your characters’ nuances, and a truer version of the story.”

The adaptation now on release of King’s monumental series of novels The Dark Tower, condensed into a hollow 90-minute sequel, feels like an admission of film defeat. Apicella, though, believes King will always find a ready cinema home. “We experience horror in such a visceral way that it makes sense that you would want to share that in a cinema space,” she says, “where it becomes this communal thing. The blind terror you get when reading is also about human connection. I also find it heartening how King has such a humanitarian, moral sense, and doesn’t write about a foreign time or class, but ordinary people. He’s got such a no nonsense, truthful approach to writing, and we’re patronised and lied to so much in the world. He doesn’t do that. You receive that gratefully as a reader and viewer, that someone is just being straight with you.”

BFI Southbank’s 'Stephen King On Screen' season begins on 1 September. 'IT' is released in cinemas from 8 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments