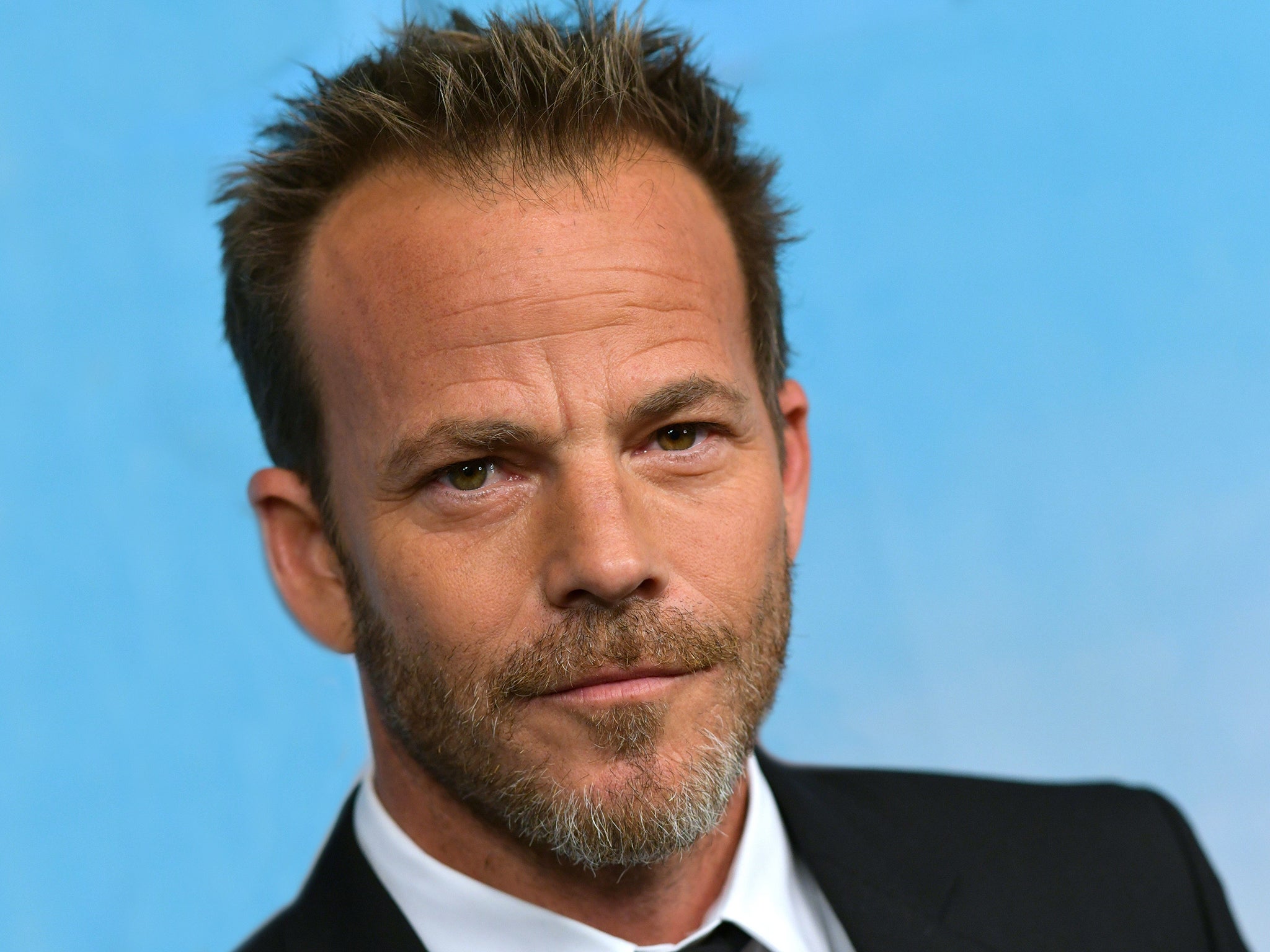

Stephen Dorff: ‘I don’t want to be in Black Widow or one of those movies – I’m embarrassed for Scarlett!’

The actor who went his own wild, wilful way after being tipped for superstardom is back playing a cage fighter in his new film ‘Embattled’; he talks to Adam White about what’s wrong with Hollywood, not being a bulls*****r and the death of his ‘little brother’ Andrew

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Stephen Dorff is despairing of it all. “This year’s Oscars were the most embarrassing thing I’ve ever seen,” he cracks, through puffs of an e-cigarette. “My business is becoming a big game show. You have actors that don’t have a clue what they’re doing. You have filmmakers that don’t have a clue what they’re doing. We’re all in these little boxes on these streamers. TV, film – it’s all one big clusterf**k of content now.”

Dorff, that grizzled, swaggering star of Backbeat (1994), Blade (1998) and Somewhere (2010), doesn’t know a sentence he can’t make a monologue. Ask a simple question and dozens of different threads emerge in his answer. His famous cheekbones slowly enveloped in smoke, he spins off from award shows to tales of Hollywood agents, the future of cable television and the time Pulp Fiction made John Travolta a star again. No matter the detour, though, everything seems to conclude in defiance.

“I still hunt out the good s**t because I don’t want to be in Black Widow,” he says. “It looks like garbage to me. It looks like a bad video game. I’m embarrassed for those people. I’m embarrassed for Scarlett! I’m sure she got paid five, seven million bucks, but I’m embarrassed for her. I don’t want to be in those movies. I really don’t. I’ll find that kid director that’s gonna be the next Kubrick and I’ll act for him instead.”

The 47-year-old may be speaking over Zoom from his home in Tennessee, but the mood is of an off-the-record hang at the back of a dive bar. Dorff is honest, sometimes to a fault, audacious and high-energy, and wearing his years well. He has the knowing ambivalence of someone who’s clearly lived a lot of life and had a blast doing it. “I don’t have a family yet and I don’t have five ex-wives that I have to pay for,” he jokes. “I pretty much still only have me to deal with.”

In the mid-Nineties, Dorff was often proclaimed one of Hollywood’s next big things. He had a compelling backstory – he’s the son of a successful country music songwriter, and was something of a hellion in his youth, having been kicked out of multiple Los Angeles schools; he also had a reputation for partying, promiscuity and overindulging. In 1996, he shared a Vanity Fair cover, one of those annual ones proclaiming the stars of the future, with Leonardo DiCaprio, Matthew McConaughey and Will Smith. But there was always something a little less polished about him than those soon-to-be icons.

He found a niche playing agents of chaos – the arch-nemesis of Wesley Snipes’s vampiric Blade; a kamikaze filmmaker in John Waters’s Cecil B DeMented (2000); a plaid-wearing misanthrope in the Gen-X thriller SFW (1994). Embattled, his new film, follows suit. It’s an engrossing family drama with Dorff as an MMA fighter. We meet his character, the volatile Cash Boykins, boasting about the gargantuan size of his appendage. He spews homophobia and hurt with regularity, and treats his teenage son (an affecting Darren Mann) as a punching bag. The film is about masculinity, paternity and how fame corrupts. Dorff struggled to let it go.

“I was the angriest and most aggressive person I’d ever been on a movie set,” he explains. “To the point where I don’t think many people liked me on that set. After the movie wrapped, I apologised. I had to do what I had to do. But that’s my job here. It’s not summer camp, I’m not here to be everybody’s best friend.” He breaks, then revs up again. “Normally, I can turn s**t on and turn it off like nobody’s business. I’m not really a believer in method acting, but this [character] was hard to lose. For about two weeks, I just couldn’t get rid of this f**king energy.” It was worth it, though. “A year later, I see the movie and I was really blown away, you know? I thought... Jesus.”

Dorff’s surprise at his own acting ability is a kind of growth. In his early twenties, he was happy to declare himself the most talented movie star in Hollywood. The time was 1994, a year after Dorff became a pin-up courtesy of an Aerosmith video – he was Alicia Silverstone’s dirtbag boyfriend in “Cryin” – and arthouse dramas like The Power of One (1992), and he had just given an infamous interview to Movieline Magazine in which he threw casual grenades at nearly all of his peers. Christian Slater, Chris O’Donnell and Mark Wahlberg all came in for a battering. He boasted that he was the best the industry had to offer, and that, ultimately, the projects he chose and his resistance to the movie-star machine will prove it. “In the end,” he pledged back then, “my filmography is going to be pretty cool.”

Dorff was cocky, sure, but he also turned out to be correct. While he didn’t star in Scent of a Woman or Titanic – he was second choice to O’Donnell and DiCaprio, respectively – he never seemed the right fit for romantic leads anyway. Instead, his CV is full of fascinating oddities: the wild sci-fi comedy Space Truckers (1996), Lee Daniels’s X-rated pulp thriller Shadowboxer (2005), or his remarkable turn as the trans icon Candy Darling in I Shot Andy Warhol (1996). “I don’t like playing things too safe,” he says today. “To me, Hollywood’s always too safe. When I’ve needed money, sure, I’ve done a couple of weeks on a movie that I didn’t wanna do. See, I like money too, because I like to buy things and I like art and real estate.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

But there needs to be balance, too. He remembers his agents wanting him to do “some sh*tty movie” he doesn’t remember, and choosing to do Cecil B DeMented instead. “Why wouldn’t I do a John Waters movie? The other movie sucks! They’re like, well, it’s not gonna do anything for your career or money-wise. But I’m gonna go to Cannes and we’re gonna have a standing ovation, and kids around the world, art students and John Waters fans are going to worship this f**king movie, which they do to this day. Why wouldn’t I do that?” He grins. “So I fired those agents.”

I don’t have five ex-wives that I have to pay for – I pretty much still only have me to deal with

Dorff has mellowed a lot since his wilder years, but there’s still a rebellious streak there. Getting beneath the bravado won’t be achieved in the time I have in his company. But there are glimmers of a humbler self here and there – in his reverence when he talks about his family, or his excitement about the movies he has in the pipeline, or his continued love for Jack Nicholson, his co-star in the underrated noir Blood and Wine (1997). In 2010, when Sofia Coppola was asked to explain why she had chosen Dorff to play a multi-faceted if directionless movie star in her film Somewhere, she said that he was an old friend of hers, with levels to his personality that most don’t see. “He has a real sweetness that is a contrast to his kind of macho image,” she told IndieWire. “But he’s actually a really sincere, sweet guy.”

Why did it tend to be hidden from the world so much? “I think most of the films that I do tend to be edgier,” he reckons. “But Sofia saw something in me.” He shifts his jaw from side to side. “Look, I’m not – in my personal life, I’m pretty funny, and I’m pretty light. I don’t walk around like some of my dramatic actor friends. They seem tortured all the time – I don’t! I’m not gonna sit here and say how sweet I am, but I’ve always felt like I’m pretty genuine. I’m not a bulls***ter. I’ve never really been a fan of that. I can read people in two minutes, whether I like them, or if I think they’re smart or I think they’re f***ing idiots. I have a very good radar for that.”

Somewhere arrived in Dorff’s lap on the one-year anniversary of his mother’s death. His recent run of strong roles – Embattled, the acclaimed third season of True Detective and the experimental country music drama Wheeler – all came about on the heels of the death of his brother, songwriter Andrew Dorff. “I get all these gifts after I lose people and it kind of sucks,” he says, as if he’s still confused by the timings of it all. “I was in a terrible place when I lost my little brother. I didn’t really want to act any more. But then all these nice things started happening. I don’t know if that’s because of the gods or what.”

He falls silent, for the only real time in our conversation. Then he lets out a raspy laugh, inhales from his e-cig and comes alive again. “My brother would want me to act and it’s what I f**king do, so I should probably do it.”

‘Embattled’ is available on digital download from 5 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments