Sara Driver on getting behind the camera for the first time in 24 years: ‘It's still so difficult for women’

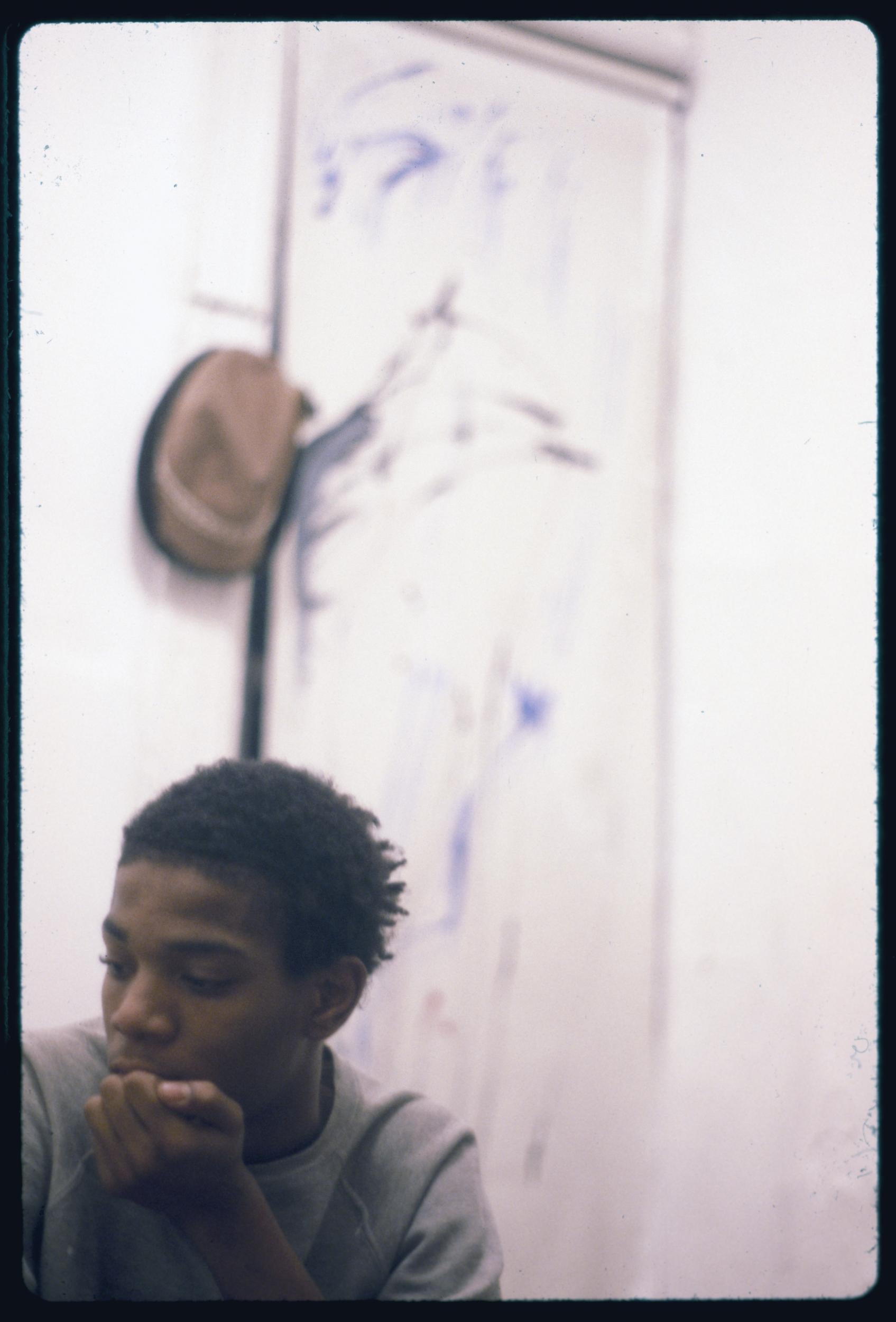

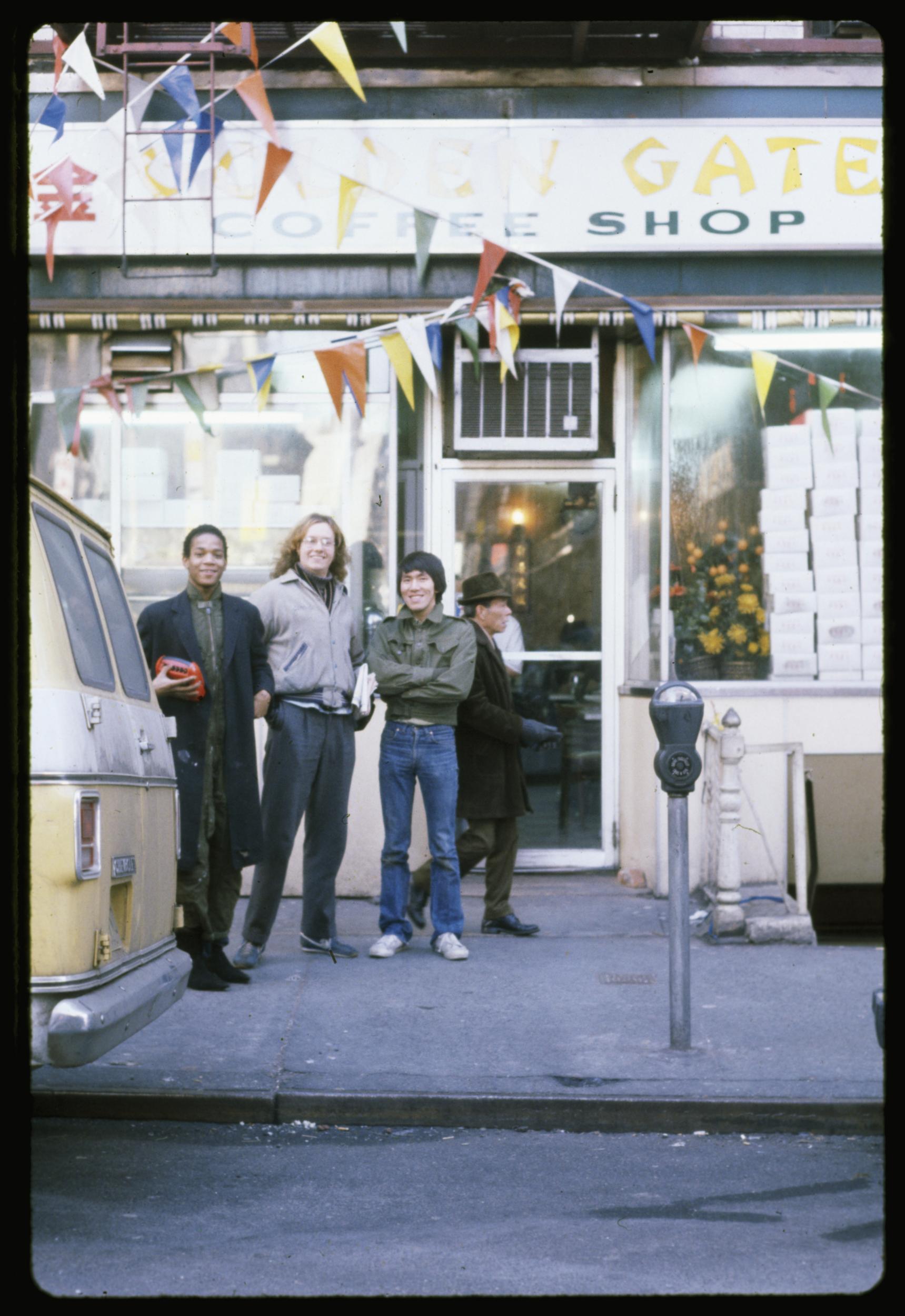

The filmmaker is back, with a documentary about artist Jean-Michel Basquiat and the New York scene they were both part of in the late Seventies

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was Hurricane Sandy that was the unlikely stimulus for Sara Driver to return to the director’s chair after a 24-year hiatus. Her documentary Boom For Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat is a candid account of the New York artist told by those who – like Driver herself – used to party with him.

“There was a huge flood on the lower East Side, caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012,” Driver tells me in the lobby of the Andaz Hotel, when we meet before the film opened the East End Film Festival.

“My friend Alexis Adler panicked. She had been storing memorabilia and works by Basquiat, which dates from when she lived with the artist.

“Luckily, everything was safe and also there was way more stuff than she remembered, drawings, clothes and writings. I was the first person she told and it seemed like a window, a treasure trove, stuff that sparked my memory.”

Driver was a film student at NYU in the years that the film covers from 1978 to 1981. A classmate of Spike Lee, the film school was where she met her partner and collaborator Jim Jarmusch. Life revolved around production, the edit suite and frequenting the legendary Mud Club, where Basquiat could usually be found creating mischief.

Driver recalls, “It was always night time at that time of my life. It was before the art boom, before the real estate boom. Nobody was thinking about money. We were all trying to be musicians and artists. It was a very weird zeitgeist thing, because it was this very natural art community that formed in this very burned out and dangerous part of New York City, so we were watching each other’s backs as well.”

She still looks like a rock star at 62, her blonde hair falls over the shoulders of her thin frame. She oozes cool. Yet back in the day, she had a very different aesthetic.

“I was editing into the night and my home was a few blocks away, but because the streets were so dangerous I cut my hair so it was just an inch long around my head, and I walked like a boy so that people would not bother me.”

Yet Driver turned out not to be ‘man’ enough for her chosen profession – despite a string of early hits, her career floundered. And the misogyny of the filmmaking industry is surely to blame.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

For a while, it all seemed so promising. Her mid-length 1981 graduation film You are Not I is based on a Paul Bowles story and was proclaimed by French film bible Cahiers du Cinéma as one of the best films of the 1980s. Her supernatural feature film debut Sleepwalk (1986) was hailed by the New York Times for being “lyrical, witty and having the illogical sense of a dream” and debuted at the Cannes Film Festival.

Driver had a central role in making New York the mecca for independent auteurs working outside of the studio system. She produced Jarmusch’s seminal early films Permanent Vacation (1980) and Stranger Than Paradise (1984), hailed by many as the landmark work for independent filmmakers.

The couple refused to play the game: they were almost locked out of an awards ceremony feting their film, because they did not have or own formal evening wear. The apartment they stayed in had a dodgy water supply, so one day Jarmusch had to brush his teeth using tea before a day of interviews. After they sold Stranger Than Paradise at Cannes, they could make rent.

So how is it that her 1993 film, When Pigs Fly, starring Marianne Faithfull and Alfred Molina, was the last film this incredible talent made? The answer is a case study in the sexism of the American movie scene.

Driver was born in New York City but grew up across the Hudson in New Jersey. Her dad commuted to the city. Warhol was ruling over Manhattan and Driver knew that one day she would be living among the giant tower blocks.

She had originally wanted to be an archaeologist: “I had studied in Greece and I realised that I would never be able to have my own dig and that academia was really white male driven. So it’s kind of ironic that I picked another field that is white male driven.”

When she went to film school, there were only a handful of female directors that were internationally known. She cites Agnes Varda, Claudia Weill and Lina Wertmüller, who, also rather ironically, occasionally worked under male pseudonyms, Nathan Wich and George H. Brown.

“My thing was going to the movies a lot and educating myself about European cinema,” she recalls. “Then having the opportunity to make a low budget film and getting festivals to invite you across Europe and meeting other filmmakers and seeing their work.”

But somehow, her career never really progressed.

“I’m still kind of baffled by this whole question as to why it’s so difficult for women to get ahead as filmmakers,” she says.

Yet her personal experiences go some way to explaining it. “I remember another filmmaker from the scene said to me why don’t you just put on your stilettos and forget about all this camera stuff. That made me more pissed off and determined.”

Jarmusch threw her in at the deep end when he asked her to produce his films: “He told me to get him 15 locations for free.” But she says that while the union guys bent over backwards to help her, it was a totally different story when it came to financiers: “I think it’s very unfortunate that women are treated as if they can’t handle money.”

Driver didn’t ever stop wanting to make films, but nobody in the industry would let her make what she wanted: films with three-dimensional female characters. She tried to adapt Jane Bowles modernist cult classic Two Serious Ladies, which tells how two ‘respectable’ ladies descent into debauchery.

“I would have producers sit down and say ‘the script is great but who do you want as the male lead?’ I would say: ‘It’s called Two Serious Ladies’.”

With these barriers it’s no wonder she had to take jobs teaching film, and was forced into what the public and media presented as the ‘muse’ role. She inspired the idea for Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers and is credited as ‘Instigation and inspiration’ for his hip vampire romance Only Lovers Left Alive (having met Driver, the Tilda Swinton character makes so much more sense).

But the filmmaker is not a fan of being called his muse: “I think better than muse… I’m an instigator, not only for Jim, but for others too. I am working on my gravestone: if I earn that description on it, I will have lived a full and complete life.”

She may be credited as an instigator, but it’s clear that really, she should have been allowed front and centre, making movies. So while we can lament on all the films that might have been, we can at least be thankful of having the opportunity to hear her voice now.

Boom for Real is about the birth of an artist and New York. She’s less interested so much in the tales of Basquiat turning tricks or constantly doing drugs than she is about what his work says about the time and city she loves. And she’s not a big fan of how gentrification has changed her home city.

“I used to keep journals of weird things, because I used to witness a lot of weird stuff in New York,” she remembers. “The streets then had such a life of its own. If you were in a bad mood and went outside everyone picked on you. If you were happy everyone was nice. There was an emotional exchange going on all the time with people – and I miss that a lot.”

It was the urgent need to document Alexis Adler’s collection that drove her back behind the camera. “When I saw what Alexis had, I thought we need to record this while it’s intact. There was a moment where it could have all been split up; now it’s travelling in museum shows,” she says. “The beauty of making this film is that I just finally bought a camera.”

‘Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat’ is out 22 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments