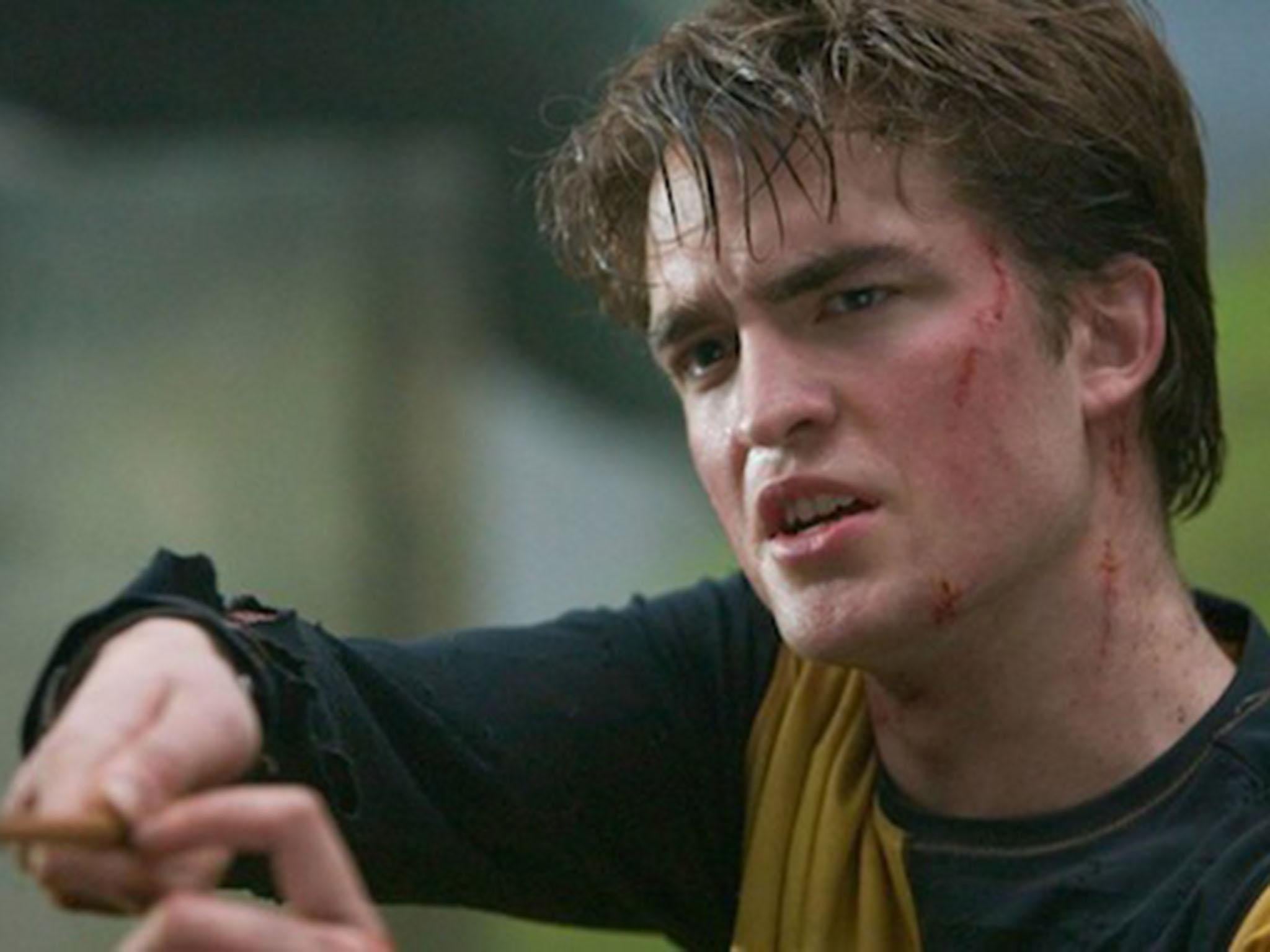

Robert Pattinson on new film Good Time, Twilight and ugly roles

The British actor who rose to fame in the 'Twilight' franchise is tipped for Oscar success after a six-minute standing ovation following the screening of 'Good Time' at the Cannes Film Festival

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last week, I had an espresso with Robert Pattinson on a rooftop terrace overlooking the Mediterranean.

That is the kind of preposterous sentence that a critic sometimes finds herself writing from the Cannes Film Festival, where Pattison’s new movie, Good Time, was in competition. The next morning, the movie shook up a largely listless event that has been stuffed with near-misses and entries that tend to preach at viewers or punish them, often both. Good Time, by contrast, is pure cinematic pleasure about an often funny, sometimes shocking rush into the abyss, one that earned Pattinson a lot of critical love here, if no awards.

Pattinson plays Constantine Nikas, aka Connie, a calamitously inept bad guy who, during one terrible New York adventure, leaves ruin and broken bodies in his wake. Directed by the brothers Josh and Benny Safdie, Good Time is thrillingly energetic and focused. It doesn’t peddle a message or redemption, but instead tethers you to an oblivious narcissist who pushes the story into an ever-deepening downward spiral. As errors turn into catastrophes, Connie grows increasingly feral, becoming a character who is a biliously funny reproach to the American triumphalism that suffuses superhero flicks and indies alike and insists that success isn’t just inevitable but also a birthright.

Good Time is part of a fascinating course correction undertaken by Pattinson, who in recent years has appeared and almost disappeared in art cinema titles like The Childhood of a Leader and The Lost City of Z. Although he brushed against blockbuster fame playing a doomed character in the Harry Potter franchise, he became a global name in the role of Edward Cullen, the pallid vampire heartthrob in the Twilight series.

That celebrity turned frenzied when Pattinson and his co-star Kristen Stewart began a long on-and-off relationship that quickly turned into fodder for the publicity grinder and was almost inevitably folded into the Twilight brand and saga.

During his Twilight years, Pattinson was not always treated kindly by critics who did not necessarily see beyond his beauty or his utility as one of that series’ cinematic objects of desire. Unlike Stewart, he also did not have an earlier body of work that indicated he could do more than pout prettily, even if his turns in small movies like Remember Me (2010) showed promise.

It was, however, Cosmopolis, the 2012 dystopian fantasy from David Cronenberg, based on the Don DeLillo novel, that effectively set Pattinson’s career path. “I think it was the first time when I worked on something that was quite complex,” he says.

Cosmopolis was, he adds, essentially the first movie he made after he finished the final chapter of the Twilight series. “I especially love the fact that it came out really at the height of my popularity,” he says. Cast as a master of the universe who endures a spectacular, increasingly violent and humiliating fall, Pattinson sees the movie as “the big turning point for me — I just realized that was what I wanted to do.”

Cronenberg had made a movie without a mould, and his star became eager to follow suit. “I think it’s so rare for something to break a pattern,” Pattinson continues. “I feel like almost everything in the world is designed to be predictable."image

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Movie stardom depends on charisma and that alchemical quality called presence, as well as a certain amount of predictability and patterns, genres and types. But longevity means occasionally breaking patterns. Pattinson is clearly set on avoiding obviousness, and this may be why, instructively, he has gravitated toward roles that call for his characters to undergo punishing physical abuse — they’ve been beaten, throttled, shot and endured a proctologist’s probing — as if he were trying to expunge the last trace of Edward. This at times seems to go beyond the showy, self-regarding transformations that stars like to take on, into a deeper transfiguration.

It’s common for stars to obscure their looks, pop on a fake nose and fright wig, of course; it’s less common for actors to wholly embrace the irredeemable and risk the audience’s love. “Anyone can look ugly,” Pattinson says. “It doesn’t take much.”

In Good Time, the ugliness he taps into goes beyond Connie’s greasy hair and torrents of flop sweat, and seems to exude from his very pores. Pattinson, who conveys a warmth and openness in person, conceded that it could be a problem when audiences confuse actor and character. But that hasn’t happened to him, which is why he is, he said, “pretty blasé about it.” If anything, he seemed happy at all the “revolting parts” he has coming up.

Looking further ahead, he would love to work with the German director Maren Ade, whose Toni Erdmann played big at Cannes last year. During this year’s festival, it was announced that Pattinson would star in The Souvenir, an ambitious movie from the British director Joanna Hogg that Martin Scorsese will executive produce. Pattinson also hopes that this summer he can start on a project (High Life) that he and the French director Claire Denis – he counts her film White Material among his favourites – have been working on for three years. (“That, to me, that’s kind of the biggest thing I’ve got. I literally still can’t really believe it.”)

“I think one of the best things, basically, about being a bit of a sellout,” Pattinson says, is “if you’ve done five movies in a series, you’ve had to accept some responsibility for playing the same character.”

He didn’t sound regretful, just matter-of-fact. Working on the Twilight movies, he says, was “an amazing luxury” and it was “amazing luck, as well, to just have fallen into it with the group of people I worked with on it.” They were kids in it together, kids who rebelled or tried to, and felt emboldened to act out. He even came close, he says, to being fired on the first movie, until his agents flew in to straighten him out. “I didn’t have to kiss anybody’s rear end the entire time,” he said. “I don’t think I did, anyway.”

Pattinson seems entirely at peace with Twilight and has clearly found a way to harness its legacy, which includes going dark and making the kinds of art films that find love at Cannes. He says he always thinks he’s terrible in every take.

“I can’t say that about anyone I work with,” he added. “I’ve never seen anyone give themselves such a hard time. I’m beating myself up afterward. And I think there’s some weird perverted energy that comes out of when people criticise previous work or think you represent this certain thing; it gives you this energy.”

Maybe that sounds disingenuous, but I believed him. He was on a roll, though, and soon added that he was “almost scared of anyone saying anything I do is good.” He then laughed, perhaps a touch self-consciously.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments