Rita Hayworth at 100: The Hollywood star trapped by her greatest role

'Every man I knew went to bed with Gilda and woke up with me'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In Stephen King’s novella Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, prison inmate Andy Dufresne gradually digs an escape tunnel through the wall of his cell, covering up his handiwork night after night under a poster of the eponymous Hollywood icon smuggled inside by a friend.

The story, part of the collection Different Seasons (1982), opens in 1947 and the plot point neatly captures the spell the “Love Goddess” cast over the public imagination in that particular moment, her appearance as a femme fatale in Gilda (1946) arguably the defining film role of the 1940s.

Hayworth – born 100 years ago this week – was a favourite pin-up among lonely American servicemen fighting overseas during the Second World War.

A particular publicity photograph of her kneeling on a bed in a lacy negligee from a 1941 issue of Life magazine stared down from many a barrack and bunk room wall across Europe and the Pacific, reminding the troops – like Andy Dufrense – of better days at home and the promise of a brighter tomorrow.

Her beaming smile, auburn hair and dazzling coal-dark eyes were so much a part of the GIs’ world they even taped another image of her, torn out of Esquire, onto the Able atom bomb dropped on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands on 1 July 1946. Never has the tabloid adjective “bombshell” been more apt.

But she was always far more than a sex symbol, that reductive label entirely failing to convey the oddly wholesome sensuality and wry intelligence she brought to the cinema screen. Despite her knockout beauty, Hayworth always had an approachable quality, an obvious, beckoning sense of fun.

For all her mid-century fame, the star is often thought of today as a tragic figure, remembered more for her string of failed marriages, her abrupt professional decline in the 1960s, her sad death from Alzheimer’s and for being hopelessly typecast by that one signature role.

“Every man I knew went to bed with Gilda and woke up with me,” she famously lamented.

In Charles Vidor’s superb noir, Gilda is a siren, drawing the eyes of every hapless punter she encounters in the Buenos Aires gambling hall operated by her husband, Ballin Mundsun (George Macready).

She finds herself at the centre of a complex love triangle when Glenn Ford’s American drifter Johnny Farrell arrives in town and takes a job overseeing the casino’s roulette tables.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Mundsun, a faux-aristocrat with a spring-loaded knife in the end of his cane, appears to take a masochistic pleasure in the spectacle of his wife stirring the lusts of strangers, more than tolerating her obvious lies about where she disappears to at night.

Johnny, apparently fiercely loyal to his shady employer, states his disapproval of Gilda: “I hated her so I couldn’t get her out of my mind for a minute.”

“Hate is a very exciting emotion. Haven’t you noticed? Very exciting. I hate you too Johnny. I hate you so much that I would destroy myself to take you down with me,” she tells him.

It's sizzling stuff, the atmosphere throughout as stifling as a balmy afternoon on the waterfront.

Hayworth’s introduction singing the torch song “Put the Blame on Mame” – itself a warning to the foolish – is as eye-catching an entrance as has ever been made and would provide the inspiration for Jessica Rabbit in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988).

“Decent? Me?” she laughs, throwing back her hair, a scene that provides loud cheers and applause when Gilda is shown to the prisoners in Frank Darabont’s 1994 adaptation of The Shawshank Redemption.

No one could hope to live up to such a part and Rita Hayworth, though justly proud of her performance, would become exasperated at being so inescapably associated with it and seeing so much of the rest of her body of work overlooked as a result.

Born Margarita Carmen Cansino in Brooklyn on 17 October 1918, she was the daughter of Eduardo Cansino, a professional Spanish dancer, and Volga Hayworth, an Irish-American showgirl who had performed on Broadway with the Ziegfeld Follies.

Dancing herself from an early age, she was spotted by Warner Brothers aged eight and invited to appear in the short film La Fiesta in 1926. The family quickly relocated to Hollywood where Eduardo opened his own studio and taught stars like James Cagney and Jean Harlow the flamenco.

Plucked from high school at 12 to tour the night clubs of Tijuana, Mexico, as her father’s partner in the Dancing Cansinos, the young Hayworth was a shy child and knew only a life of strict rehearsals and rigorous discipline in the pursuit of perfection.

After being spotted by Fox executive William Sheehan at 16, she was handed a contract and danced in the Spencer Tracey vehicle Dante’s Inferno (1935).

When mogul Darryl F Zanuck dropped her, Eduardo Cansino hired Los Angeles car salesman Edward Judson to manage his daughter. Judson, 40, married Rita, 18, and got her on the payroll at Columbia, but not without promising sexual favours on behalf of his young wife to the cruel and controlling studio boss Harry Cohn.

Gradually working her way up, Hayworth’s early career highlights included a vamp role in Only Angels Have Wings (1939) with Cary Grant and Jean Arthur for Howard Hawks and a supporting turn in Angels over Broadway (1940), an eccentric comedy-drama from the pen of journalist Ben Hecht.

She made waves as the second female lead in Raoul Walsh’s “naughty Nineties” period musical The Strawberry Blonde (1941) opposite Cagney and Olivia de Havilland before setting her image in stone in the bullfight melodrama Blood and Sand (1941), a remake of a popular silent-era toreador picture starring Tyrone Power and Anthony Quinn.

Carole Landis had turned down the part of Dona Sol des Muire because she refused to dye her hair red at the request of director Rouben Mamoulian, who wanted to make the most of the Technicolor photography.

Hayworth had no such objections and proved ideal in the role due to her expertise in the tango. As choreographer Hermes Pan put it: “When Rita came on she was just dynamite. You couldn’t believe the excitement when we saw the rushes.”

Having been credited on screen as Rita Cansino until 1937’s Criminals of the Air, she was now the Rita Hayworth of myth.

While the loss of her dark Spanish mane, the raising of her hairline through painful electrolysis and the anglicising of her name might look troubling from a 21st century standpoint, Latino stars like Dolores del Rio, Lupe Velez and Linda Darnell thrived in the Hollywood Golden Age and such transformations were routine.

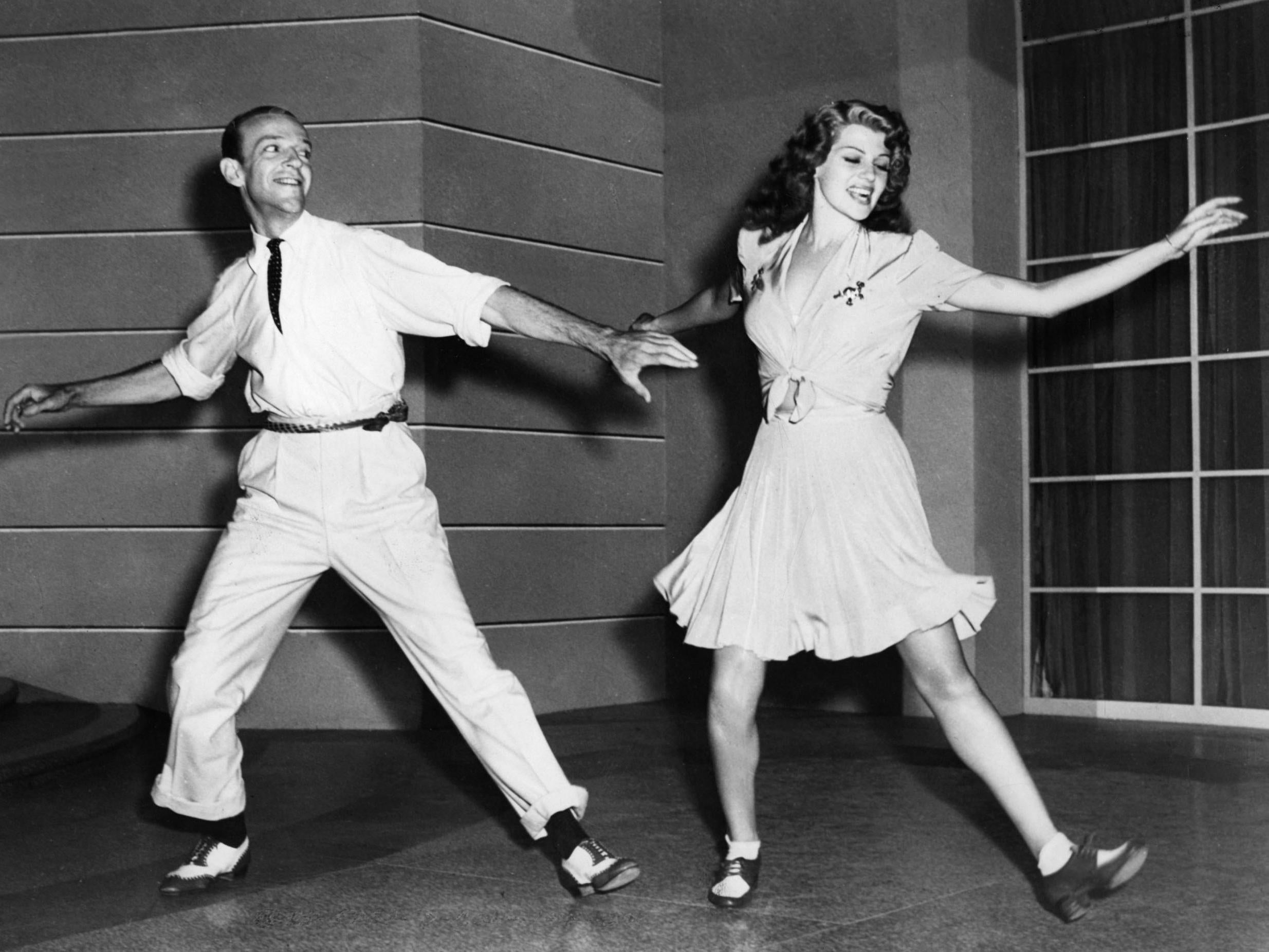

Next came a brace of musicals with Fred Astaire – You’ll Never Get Rich (1941) and You Were Never Lovelier (1942) – in which the pair were ideally matched and in which she was truly given an opportunity to show off her talents. Astaire once even declared her his favourite partner, an extraordinary compliment given his long and celebrated pairing with Ginger Rogers.

Cover Girl (1944), another lavish musical, this time opposite Gene Kelly with songs by Jerome Kern and Ira Gershwin, was a smash hit and among her proudest achievements. That film was directed by Vidor, who foresaw the darker potential of her appeal with one eye on a new screenplay that had recently crossed his desk about expat gamblers in Argentina.

Hayworth played other memorable roles after Gilda – notably another musical, Down to Earth (1947), the success of which gave her a degree of autonomy not previously available and allowed her to found her own production company and even ban the influential Hollywood gossip columnists Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons from her sets.

She then played another femme fatale, Elsa Bannister, in her second husband Orson Welles’s The Lady from Shanghai (1947), an exotic, murky and misanthropic thriller made when their marriage was falling apart. Now regarded a classic, it left audiences perplexed at the time.

Welles and Hayworth’s relationship – dubbed “Beauty and the Brain” by the newspapers – had been under strain from the beginning because of the proprietorial jealousy of Cohn, a man Welles considered “a monster”.

As Clinton Heylin explains in his book Despite The System: Orson Welles Versus the Hollywood Studios (2005), Columbia had hoped to emulate the smouldering husband-and-wife chemistry Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall had exhibited in 1946’s The Big Sleep but instead, “Welles portrayed his own screen goddess as a lying bitch who deserved to die.”

Soon after this unhappy experience she left Hollywood, shunning overtures from Aristotle Onassis and the Shah of Iran to marry promiscuous playboy Prince Aly Khan, son of the Aga Khan, a union branded “illicit” by Pope John XXIII.

Their wedding on the French Riviera, as recounted in Anne Edwards’s book Throne of Gold (1995), saw them serenaded by Yves Montand, 600 bottles of champagne drunk, 50 pounds of caviar consumed, the cake cut with an antique glass sword and a swimming pool unveiled filled to the brim with cologne.

Welles, hardly impartial, called it “a fatal marriage, the worst thing that could have happened to her. He was charming, attractive, a nice man... but the wrong husband for her.”

He was proved right and Hayworth, divorced once more, returned to Los Angeles for projects like Affair in Trinidad (1952), Salome, Miss Sadie Thompson (both 1953), Pal Joey (1957) and Separate Tables (1958) but, in truth, her moment had passed.

The disappointment of her later years, compounded by two more abusive husbands, provide an indication of how hard it was – and still is – to be a mature woman in a superficial and male-dominated industry.

Decades before the abuses of Harvey Weinstein and the revelations of the #MeToo movement, Rita Hayworth knew all about the toxic entitlement of manipulative men.

“I’ve been passed from hand to hand. I’ve had to submit to things that nice young American boys couldn’t conceive of in their wildest nightmares. I’ve lived among the ruins. Armies have marched over me,” her character says, amazingly frankly, in Fire Down Below (1957) and the actress no doubt meant every word.

At the bitter end, the dignity with which she conducted herself during her difficult struggle with Alzheimer’s – a disease then little understood – won her new admirers.

As President Ronald Reagan (himself a sufferer) wrote upon the news of her death on 14 May 1987: “Her courage and candour, and that of her family, were a great public service in bringing worldwide attention to a disease which we all hope will soon be cured.”

Despite the many sorrows of her private life, Rita Hayworth could take heart from the knowledge that her extraordinary charisma had brought joy to millions and been captured for posterity on celluloid, her most famous role alone enough to grant true immortality.

There never was a woman like Gilda.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments