Stalking. Fat jokes. A very white Notting Hill: Have Richard Curtis’s films aged horribly?

The British filmmaker behind romcoms including ‘Four Weddings’, ‘Love Actually’ and ‘Bridget Jones’ has spent the last few years lambasting his own work for its un-diverse casting and primordial gags about women with ‘sizeable arses’ and ‘huge thighs’. But critics have always had their knives out for his movies, writes Geoffrey Macnab – often overlooking their witty, charming genius

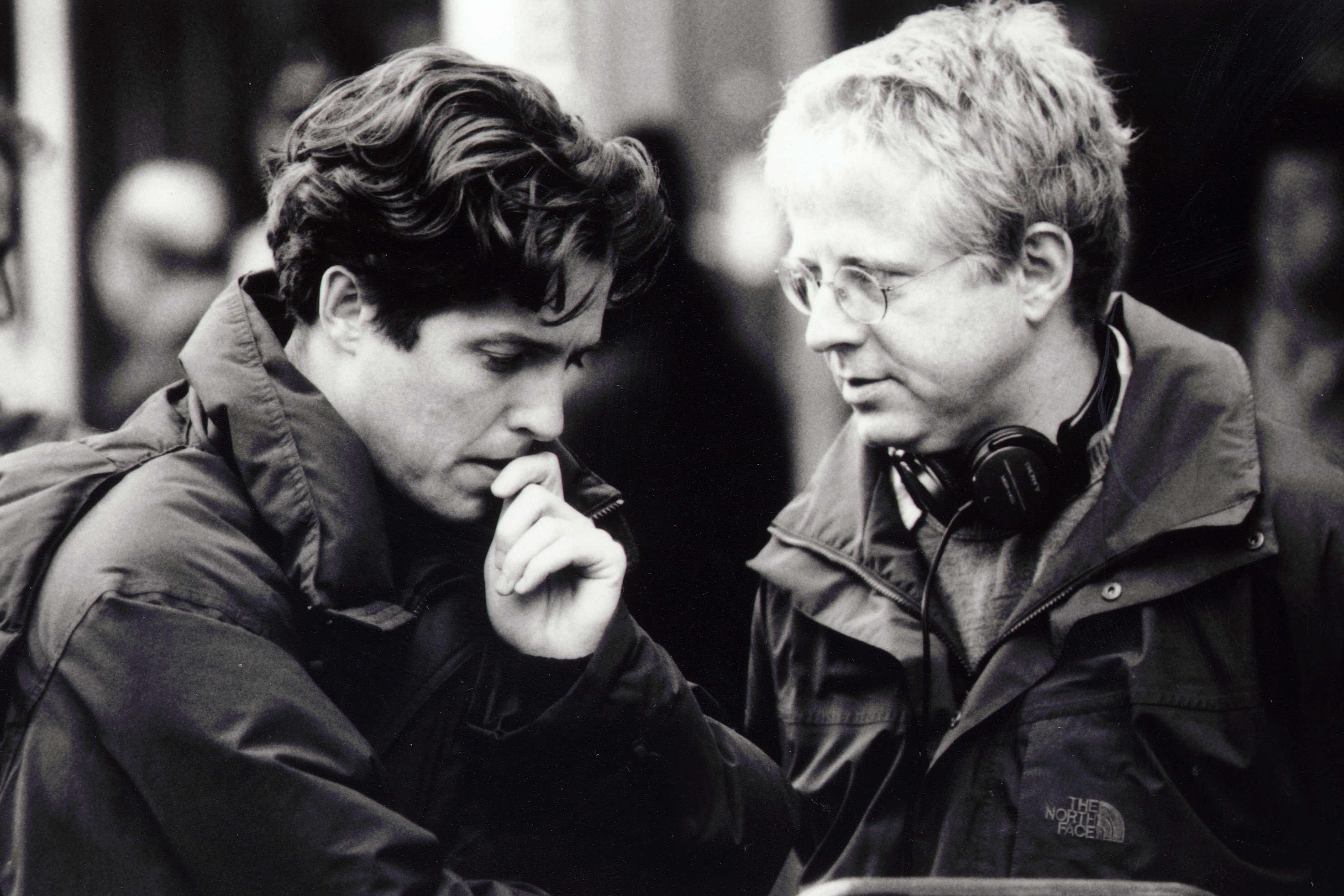

The knives have been out for Richard Curtis’s movies recently – and the one who’s most often wielded the blade has been Curtis himself. In a series of interviews, the writer-director of some of Britain’s best-loved romcoms (Notting Hill, Love Actually, Four Weddings and a Funeral) has been slashing at his own work.

Earlier this month at the Cheltenham Literature Festival, while being grilled by his daughter, Scarlett, Curtis issued several mea culpas: for the lack of people of colour in Notting Hill, and for the fat jokes in Love Actually (re-released next month to mark its 20th anniversary) and Bridget Jones’s Diary. He labelled himself “stupid and wrong”. This isn’t the first time that Curtis has called himself out. “The lack of diversity makes me feel uncomfortable and a bit stupid,” he commented in a TV special about Love Actually broadcast in the US last year. Speaking to podcaster Craig Oliver also last year, Curtis said that his children “don’t like 20 per cent of my jokes because they think they are old-fashioned and wrong somehow.”

Loop back in time to 1994, though, and you will find plenty of brickbats being thrown at Curtis – and his just-released Four Weddings and a Funeral – even then, although not by himself. Four Weddings, which Curtis scripted but was directed by Mike Newell, had been very warmly received in the US at the Sundance Film Festival, but certain reviewers were immediately hostile when it surfaced a few months later in the UK.

This breezy yarn about the burgeoning romance between scatty but charming English bachelor, Charles (Hugh Grant), and glamorous American, Carrie (Andie MacDowell), whom he meets at a series of weddings, rubbed certain critics up the wrong way. Sight and Sound magazine called it a “smarmy little fable” with “two dull protagonists” and likened the experience of watching it to being a reluctant guest at a real-life wedding: “[It’s] two hours stuck in a crowded room with a lot of people you don’t know very well and don’t particularly like.”

To its detractors, Four Weddings and its successor Notting Hill, released in 1999, seemed strangely quaint and old-fashioned. Both films portrayed a Britain that was cosy, complacent and very middle class. Their milieu was a long way removed from that of, say, Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996) with its heroin addicts running amok in downtown Leith.

Curtis offered the tousled but still debonair Grant as the dithering romantic Englishman popping up in home counties churches and quaint little west London bookshops. Boyle’s evocation of Irvine Welsh’s Edinburgh gave audiences Ewan McGregor as the pallid, skinhead junkie Renton, squatting down on his haunches and emptying his bowels in the worst and filthiest toilet in Scotland. McGregor was dirty realism. Grant was tinsel.

The Curtis films painted such a picture postcard vision of London, with gleaming red buses and familiar landmarks, that you could have been forgiven for thinking the films were commissioned by VisitBritain or the old London Tourist Board. They were modern-day fairytales and wish fulfilment fantasies. Both Four Weddings and Notting Hill borrowed heavily from the Roman Holiday playbook.

In William Wyler’s classic 1953 romcom, a beautiful princess (Audrey Hepburn) gets together with a hard-nosed reporter (Gregory Peck) after they whizz around the Eternal City on a Vespa. In Notting Hill, an A-list Hollywood star (Julia Roberts) falls for a bedraggled bookseller (Grant).

Elements of Curtis’s films can’t help but seem jarring – even creepy. For example, it’s startling to see the casual way that film extra Judy (Joanna Page) is treated in Love Actually (2003). An assistant director bluntly tells her to undress and then gets fellow extra John (Martin Freeman) to simulate sex with her. (The couple while away the time discussing traffic jams while she sits half-naked on top of him).

The relationship in the film between the prime minister (Grant again) and the biscuit-dispensing Downing Street assistant Natalie (Martine McCutcheon) is likewise grating. He is an older, richer patriarch in a position of obvious power. Curtis has understandably said that the crude lines about Natalie’s “sizeable arse” and “huge thighs” today make him squirm.

“Thank you for telling a generation of men that their intrusiveness and obsessions are ‘romantic’, and that women are secretly flattered no matter what their body language says,” wrote writer and comedian Lindy West in an evisceration of the film published by Jezebel in 2013. She accused the movie of treating its female characters like “giant bipedal vaginas in sweater vests”.

But what Curtis’s critics fail to acknowledge, and the writer himself sometimes seems to forget, is just how witty and charming these stories remain. In interviews, he often claims that, at first, he didn’t even realise he was writing romcoms. His influences were Robert Altman movies like Nashville (1975) and Short Cuts (1993) which, like Love Actually, had big ensemble casts and many different, overlapping story strands.

He was also a fan of coming-of-age films like Bill Forsyth’s Gregory’s Girl (1980), with John Gordon Sinclair as the lanky, awkward adolescent learning about love, and Barry Levinson’s Diner (1982) with its famous pecker-in-the-popcorn scene. Those films had a certain laddish sensibility and therefore weren’t attacked for their representation of women. The men in them were expected to be naive, hapless and to behave badly, especially where relationships and sex were concerned.

Curtis had refined his comic talents by writing all those episodes of TV’s Blackadder and Mr. Bean, working on both with his friend and mentor, Rowan Atkinson. He knew how to be funny and his films generally came with an emotional kick, too. They might have had moments that made you cringe, but the self-deprecating humour kept the stories from seeming maudlin – and it would be quite a stretch to suggest that Hugh Grant embodied toxic masculinity.

Grant later claimed that Curtis had “hated me on sight” at his audition for Four Weddings, and that he was cast only because Newell fought for him. Whatever the case, Grant soon became as important to Curtis’s films as Marlene Dietrich had been to those of Josef Von Sternberg. As Curtis confessed to Sue Lawley on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs in 1999, Grant was the only one who could perform his dialogue properly.

“I have been unbelievably lucky at how beautifully he does the lines I write,” Curtis said. “I have got lucky with Hugh and have hung on to him.” He talked of the “heightened realism” with which Grant played roles in his movies, never becoming too “parodic” but not being too earnest either.

Four Weddings and Notting Hill were huge hits in the US, during a period in which most British films other than Bond movies were struggling to find audiences at home, let alone breaking through internationally. They transformed the fortunes of production company Working Title, which had also made The Tall Guy (1989), Curtis’s feature film debut as a writer.

It means that any history of UK cinema over the last 30 years would feature Curtis very prominently. Nonetheless, his screenplays can seem deeply formulaic. Opposites attract. Brits fall for Yanks. Employers become besotted by their employees. Curtis likes playing with time (2013’s About Time) and alternative reality (2019’s Yesterday).

Pop anthems will generally feature very prominently, for example “Bye Bye Baby” by the Bay City Rollers blasting away during the funeral of Liam Neeson’s wife in Love Actually. There are bound to be Beatles references. The leading male character will seem gauche and unlucky in love (“a normal duffer”, as Curtis has called his archetypal hero), but will generally find romantic fulfilment before the end credits roll. If the storytelling is getting too sombre, a Rhys Ifans type will pop up in his underwear, or somebody will suddenly start swearing.

The elements are familiar but they are always expertly mixed. Curtis is a perfectionist who pays exhaustive attention to structure. He wrote a reported 17 drafts of the Four Weddings screenplay, refining and re-refining it, responding to notes from his script editor Emma Freud (whom he finally married in September, 33 years into their relationship).

Curtis’s relationship with cinema remains uneasy. He clearly doesn’t relish the sheer grind of making movies, and he’s not a cinephile. In interviews, he’ll boast about his exhaustive knowledge of pop history but then add that he has never seen a Fellini movie. “I am not a big film fan”, he told the BBC, “but I am a great fan of popular films and going to the movies.”

Conversations with Curtis will typically begin with mention of his films, before veering off into wider discussion of his charity work: Comic Relief, which he co-founded in 1985, is estimated to have raised well over £1.5bn since then. His filmmaking seems almost an afterthought when seen alongside his prodigious philanthropic endeavours.

Audiences, though, still lap up his screen work. In spite of the blasts against it, Love Actually has become as much of a Christmas fixture as It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). The excitement over Curtis revealing that he had written a short sequel to Notting Hill (albeit a very barbed one intended for Red Nose Day) showed how much that film still meant to fans too.

As for the idea that his old romcoms are showing signs of age, a counter-argument can be made that they were already dated when they first appeared. If they are “out of step with modern feminism”, as one critic has suggested, it’s insulting to audiences to suggest that no one spotted the faultlines 20 years ago.

Viewers are savvy enough now, as many were then, to see through the fat shaming and blinkered views on gender and diversity. Some primordial gags? Sure. But Curtis’s films have an optimism and a generosity of spirit that make them very hard to dislike.

‘Love Actually’ is re-released in cinemas on 24 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments