10 Oscar-winning films that are problematic in 2024

Ahead of the 2024 Oscars, Rachel Brodsky runs through the 10 Oscar-winning films that haven’t aged well

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As society evolves, moments in films that were once beloved can start to sour in history’s proverbial rear-view mirror. When Sandy (Olivia Newton John) revamps her entire look and personality to please her boyfriend Danny (John Travolta) at the end of Grease (1978), for example. Or when the cartoon crows in Disney’s animated classic Dumbo are literally called “The Jim Crows”.

Even plenty of Academy Award-winning movies have not aged particularly well. As the 95th Academy Awards approach , here are 10 Oscar-winning films that are problematic in 2024.

Green Book (2018)

When Green Book, which won Best Picture at the 91st Academy Awards, arrived in cinemas a few years back, it quickly became a divisive topic of conversation. The picture, starring Mahershala Ali and Viggo Mortensen, enjoyed early success with audiences and sailed through awards season, but critics lambasted it as being shortsighted in its depiction of race relations.

About an unlikely friendship between a Black world-class pianist (Ali) touring the Deep South in 1962 and his bodyguard, Italian-American bouncer Tony Lip (Mortensen), Green Book was criticised for historical inaccuracies and depicting Ali’s character, Dr Don Shirley, as being a “Magical Negro” archetype whose main purpose in the film is to change a white man (Mortensen) for the better. “American buddy comedies have generally mandated equal screen time to both characters – except when one of those characters is black, and exists almost entirely to help transform his white companion on a quest toward salvation,” wrote IndieWire.

Dallas Buyers Club (2013)

This biographical drama chronicles the story of Ron Woodroof (Matthew McConaughey), an Aids patient diagnosed in the mid 1980s who distributes unapproved pharmaceutical drugs to HIV/Aids patients. One of those patients is trans woman Rayon, played by Jared Leto, who won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his portrayal. Now, critics wondered why a cisgendered actor (Leto) was offered the role instead of a trans actor. Additionally, the character, some felt, was written as less of a three-dimensional being than a vehicle for Ron’s character to get over his homophobia and transphobia. “Rayon isn’t a person, she’s a function,” wrote Paris Lees in The Independent at the time.

Annie Hall (1977)

As a film, Annie Hall has historically been lauded as one of the most beloved romantic comedies of the 20th century, winning four Oscars at the 50th Academy Awards and nominated for five in total. But it’s been a bad few years for its prolific director Woody Allen, due to the recently reexamined allegations of sexual assault from his adopted daughter Dylan Farrow (Allen has continuously denied all allegations), and made worse by HBO’s Allen v Farrow docuseries, which offers a closer look into the decades-old allegations and the subsequent media firestorm.

The allegations have trickled down into a number of Allen films, Oscar-winning or not: in particular, the Oscar-nominated Manhattan (1979) depicts the director, then in his 40s, in a relationship with a 17-year-old high school student (Mariel Hemingway). In 1995’s Mighty Aphrodite, for which supporting actor Mira Sorvino won the Oscar, 60-year-old Allen briefly romances Sorvino’s much younger (though legal) and dim-witted character. It’s a pattern that repeats itself over and over – and even in Annie Hall – an older but nebbishy and unassuming guy happens to fall into bed with a beautiful, young, usually rather innocent, woman. Such a repetition starts to feel uncomfortable – particularly given the allegations brought by Dylan Farrow.

Additionally, a number of top-tier Hollywood actors and directors have denounced Allen in recent years, with Kate Winslet, Colin Firth, Timothee Chalamet, Rachel Brosnahan, Rebecca Hall, and Greta Gerwig among the names to have publicly denounced him. Not to mention the fact that Annie Hall has a throwaway line about child molesters, one of many that show up in the director’s work over the years. Taken together, it’s difficult to regard Annie Hall in quite the same way.

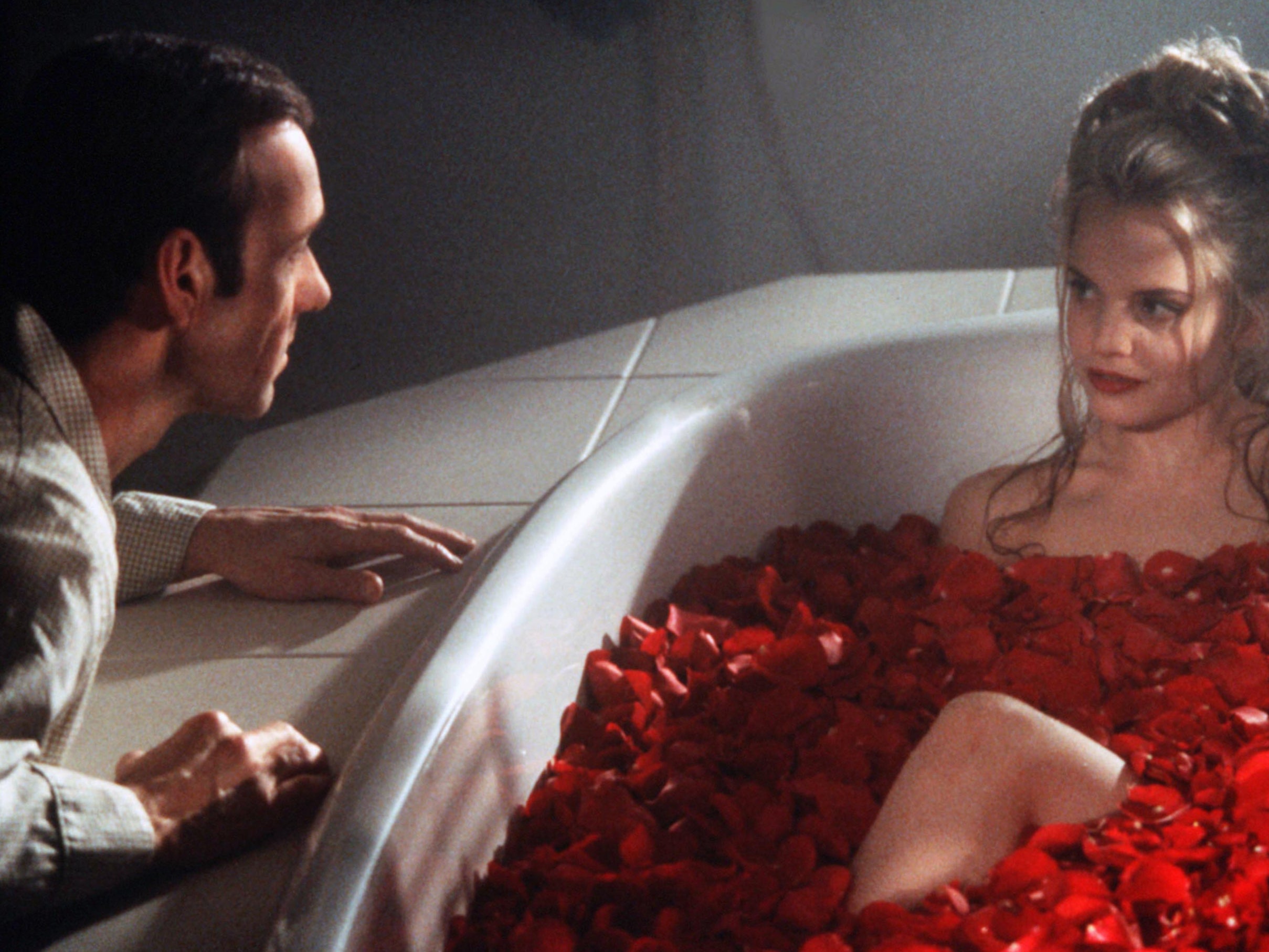

American Beauty (1999)

To begin with, the presence of disgraced actor Kevin Spacey (who won an Oscar for his role as midlife crisis-having protagonist Lester Burnham) definitely puts a damper on re-watching American Beauty, which won five Oscars in 2000, including Best Picture, Best Director (Sam Mendes), Best Screenplay (Alan Ball), and Best Actor (Spacey).

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

In October 2017, actor Anthony Rapp accused Spacey of making a sexual advance toward him in 1986, when Rapp was only 14. Following Rapp’s allegations, more men came forward with allegations that the House of Cards actor had made unwanted advances and had sexually harassed them as well. Spacey denied the claims. Rapp’s lawsuit against Spacey was dismissed last year, with a New York jury concluding that Spacey did not molest Rapp.

The film has also aged badly in its depiction of Lester’s inappropriate crush on his daughter’s (Thora Birch) teenage best friend, played by Mena Suvari. The film, of course, doesn’t act like the crush is right or OK. But its many scenes where Lester fantasises about Suvari, who is nude and covered in rose petals, caused critics at the time to liken her to a “Lolita” figure. Roger Ebert wrote at the time: “Is it wrong for a man in his 40s to lust after a teenage girl? Any honest man understands what a complicated question this is. Wrong morally, certainly, and legally. But as every woman knows, men are born with wiring that goes directly from their eyes to their genitals, bypassing the higher centers of thought. They can disapprove of their thoughts, but they cannot stop themselves from having them.”

Suffice it to say, Ebert’s “sorry, but men can’t help it” screed hasn’t aged well either.

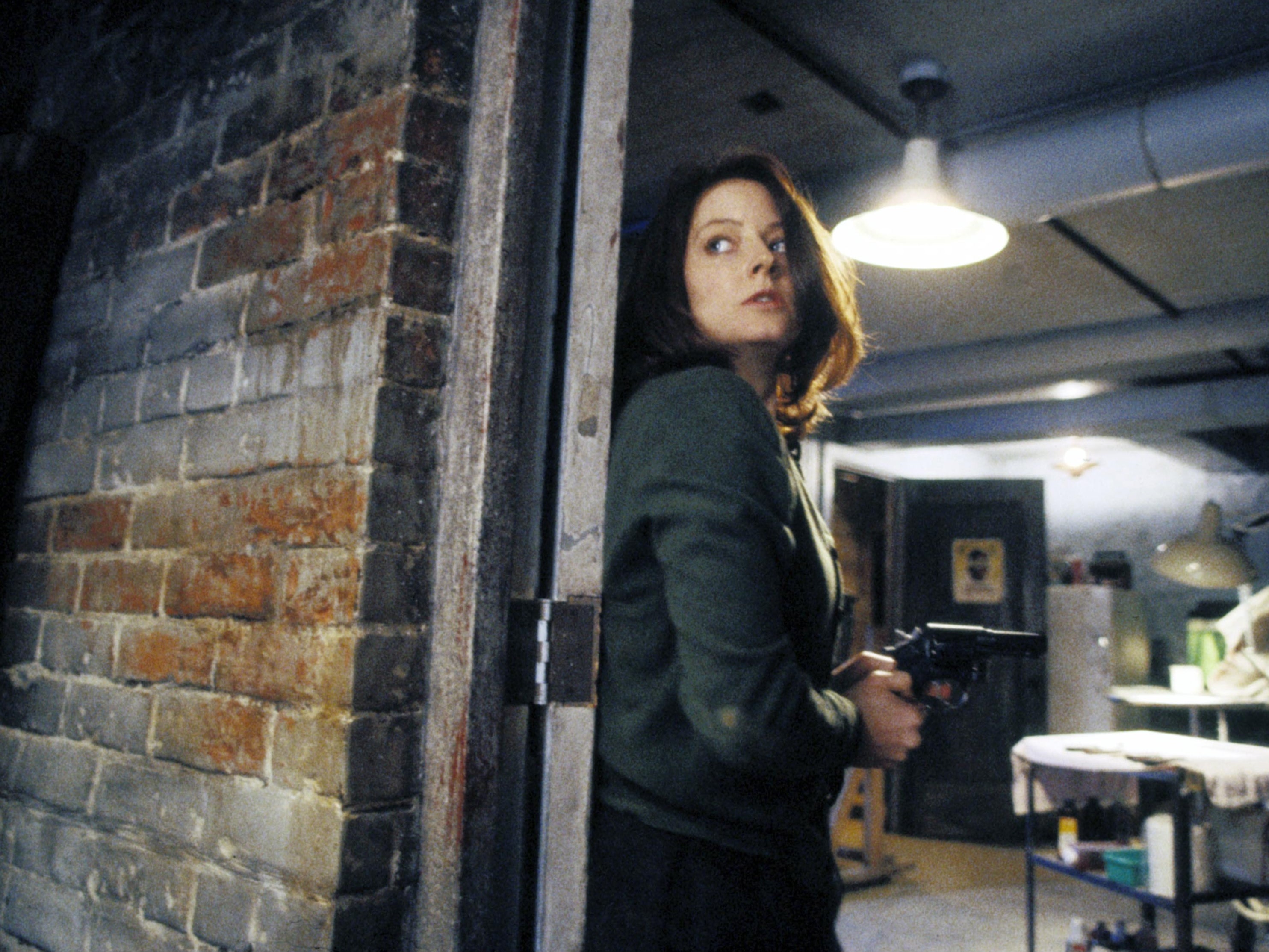

The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Another film accused of misrepresenting the transgender and/or genderqueer experience, horror standout The Silence of the Lambs, which won an Oscar for Best Picture, is criticised these days for its portrayal of villain Buffalo Bill (played by Ted Levine). Buffalo Bill is a serial killer who wears his female victims’ skins, keeps their clothes, and dresses up like them.

Though lead protagonist Clarice (Jody Foster) and her cannibal consultant Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) trade dialogue around how a) Bill isn’t transgender, and b) there’s no link between transgender identity and violence (even movie director Jonathan Demme has said that Bill is not meant to be trans), the intention is often lost on audiences. As Vox TV writer Emily VanDerWerff tweeted, “Knowing the intent of a work doesn’t mean s***, because the intent is less important than the impact. And when people saw SotL, they didn’t hear ‘Buffalo Bill isn’t trans.’ They saw a weirdo serial killer dancing around in women’s clothes.”

Driving Miss Daisy (1989)

“When Driving Miss Motherf***ng Daisy won Best Picture, that hurt,” director Spike Lee told New York Magazine in 2008. “[But] no one’s talking about Driving Miss Daisy now.”

The 1989 movie starring Jessica Tandy and Morgan Freeman, based on Alfred Uhry’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, is often (and rightly) criticised for its overly simplistic portrait of US race relations in the mid-20th century. The story of a retired schoolteacher (Tandy) living in Atlanta, who employs a Black chauffeur (Freeman), Driving Miss Daisy won Best Picture in 1989. Despite its Academy acclaim, numerous people, even Freeman, have attacked the movie as being two-dimensional, its Black characters stereotypes. In 2000, Freeman, who earned an Oscar nod for the role, referred to the movie as “a mistake” that led to him being typecast as “noble, wise, dignified”.

The Help (2011)

Another movie with noble intentions but an overly simplistic view on race relations, 2011 period drama The Help, based on the novel of the same name, is deservedly criticised for leaning on white characters to tell Black stories. Emma Stone stars as Eugenia, an aspiring journalist in Jackson, Mississippi, who wants to write a book from the point of view of the community’s Black maids, exposing the racism they regularly deal with as they work for white families.

In the years since its release, Viola Davis, who plays maid Aibileen Clark, has expressed regret over starring in The Help, saying she feels like she “betrayed myself and my people” and that the film was “created in the filter and the cesspool of systemic racism”.

Additionally, actor Bryce Dallas Howard, who also stars, has acknowledged that The Help is “told through the perspective of a white character and was created by predominantly white storytellers”.

Forrest Gump (1994)

Critics raise their eyebrows about a lot of things in Robert Zemeckis’ Oscar-winning comedy-drama, about a learning-disabled young man (Tom Hanks) who just happens to witness some of the most defining historical moments of the 20th century. The list typically includes Forrest Gump’s depiction of people with learning disabilities, protestors, and Vietnam War veterans.

The most offending detail, though, is the film’s treatment of Forrest’s best friend Jenny (Robin Wright), who is abused as a child by her father, and goes on to live a life of pure victimhood, performing at nude bars, dating abusive jerks, and eventually contracting Aids and dying young. As British GQ writer Matt Glasby put it, Jenny is “a classic mother-madonna-whore figure” who “ultimately brings Forrest redemption by shagging him, siring him a son who's clever (and Haley Joel Osment) and then, conveniently for fans of films that end, dying”.

Crash (2004)

Paul Haggis' crime drama cleaned up at the 78th Academy Awards, garnering six nominations, and winning three for Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Film Editing. Crash has, however, been critiqued as being overly simplistic about how it portrays race relations and racial stereotypes.

In 2009, when listing the Worst Movies of the Decade, Atlantic writer Ta-Nehisi Coates said, “I don't think there's a single human being in Crash. Instead you have arguments and propaganda violently bumping into each other, impressed with their own quirkiness. ('Hey look, I'm a black carjacker who resents being stereotyped.') But more than a bad film, Crash, which won an Oscar (!), is the apotheosis of a kind of unthinking, incurious, nihilistic, multiculturalism.”

Gone With the Wind (1939)

Few films have been reassessed the way Gone With the Wind has. Winning 10 Academy Awards out of 13 nominations, with Hattie McDaniel becoming the first Black woman to win an Oscar, the historical epic might have been seen as being progressive for its time, but it has decidedly not aged well. (Many will recall when HBO Max launched last year, it briefly pulled the film off the platform, citing the need for “an explanation and a denouncement” of the movie’s depictions of race relations. And, for what it’s worth, the film was heavily protested as being racist when it first came out in the 1930s.) Indeed, even filmmaker John Ridley wrote an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times lobbying for the film to be removed from HBO Max entirely. “It is a film that glorifies the antebellum south,” wrote Ridley, who won an Oscar for the 12 Years a Slave screenplay. “It is a film that, when it is not ignoring the horrors of slavery, pauses only to perpetuate some of the most painful stereotypes of people of color.”

ScreenRant’s Kayleigh Donaldson also weighed in on the film’s historical misses, writing, “The KKK are shown as heroic... Mammy, played by Hattie McDaniel, was seen as the exemplification of the Mammy archetype, a stereotype of a homely Black woman who dotes on her white boss/owner. Slavery as a whole is skimmed over by the movie, with the Civil War seen as a battle over traditional values rather than the right to literally own Black people, and the slaves shown on-screen mostly fit into the happy slave stereotype of Black men and women who were delighted by their lot in life, seen as too irresponsible to work and live free of ownership.”

This article was originally published in 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments