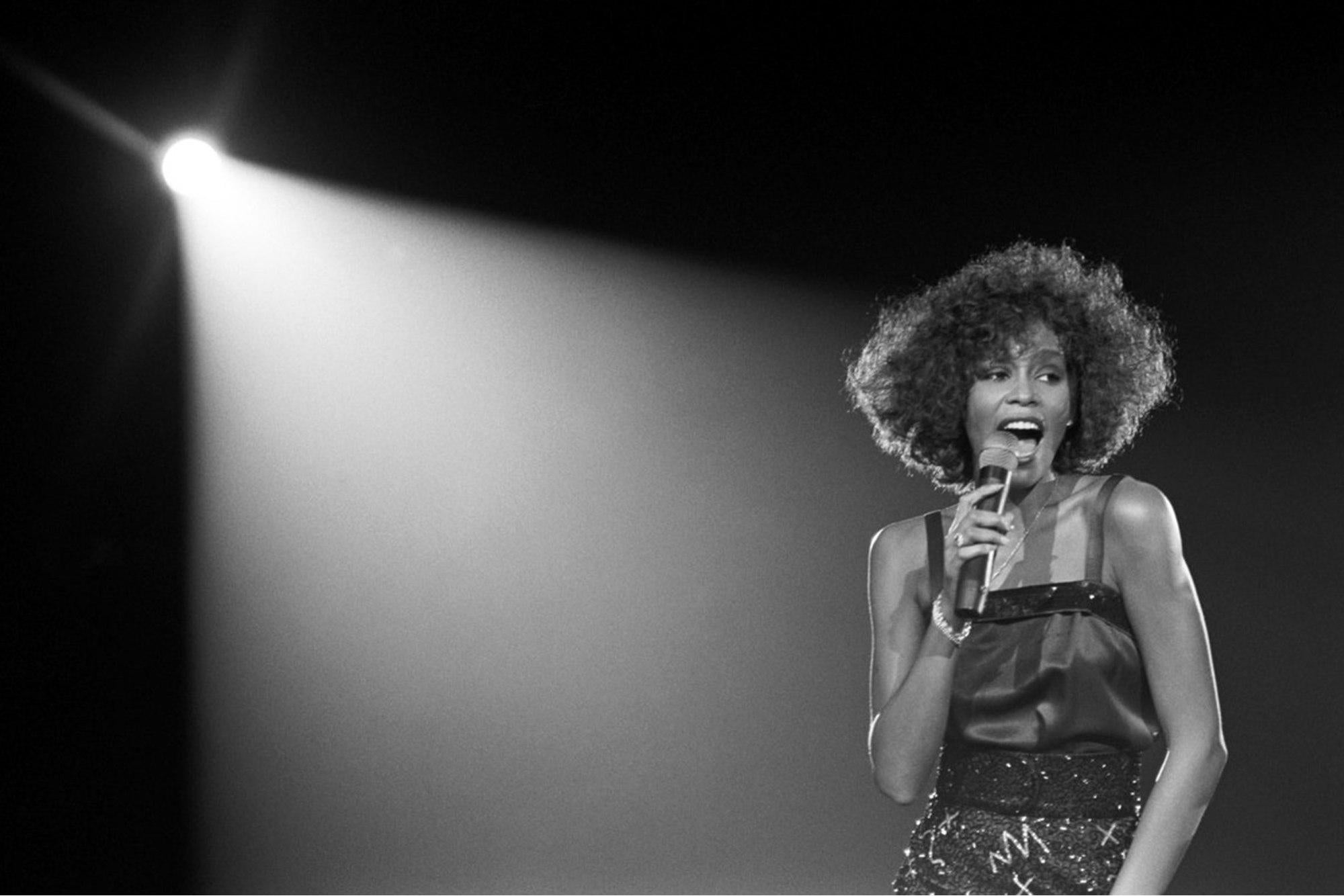

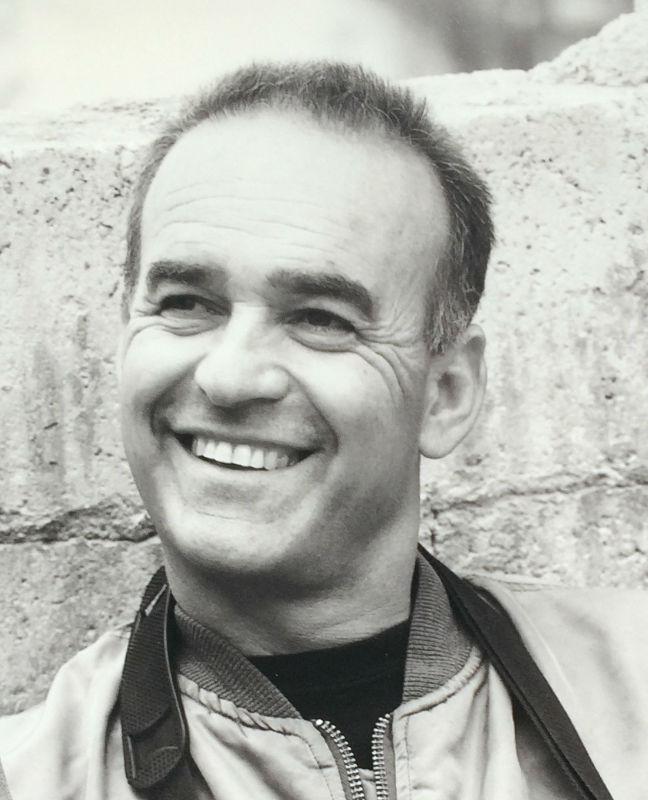

Nick Broomfield on his new documentary about Whitney Houston, its emotional impact on him and her sexuality

The new documentary 'Whitney: Can I Be Me' is about the life of the late singer whose life spiralled out of control, with large chunks of previously unseen footage

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“What a weird thing we do for a living” Nick Broomfield says to Louis Theroux as the pair finish watching a clip of Broomfield approaching Death Row Records boss, Suge Knight, in a prison yard.

The clip is taken from his 2002 film Biggie & Tupac. “We had to sign release forms to say that if we were taken as hostage they may shoot our kneecaps out,” he continues, reflecting on the film that investigated the deaths of rappers Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur. The conversation is taking place as part of this year’s Sheffield Doc/Fest and Broomfield is here to premiere his latest film, Whitney: Can I Be Me about the life of the late singer Whitney Houston.

Theroux takes a quick skip through Broomfield’s career highlights, from an early 1981 film about women going through army boot camp, Soldier Girls, to his two superb films on the life and death of the serial killer Aileen Wuornos (later played by Charlize Theron in Monster) released in 1992 and 2003.

Broomfield is one of the most distinctive and long-serving voices in British documentary filmmaking, stretching more than 30 films and four decades. For some time his trademark style was including himself in much of the film, simultaneously controlling the sound recording and holding the boom mic stick, whilst often entering the frame to ask penetrating questions and conduct interviews, projecting the image of a crew member gone rogue. Another trademark that surfaced often was documenting the failures of the documentary itself, as some films become a never-ending chase for access to his subjects, such as the cat-and-mouse game he played with Margaret Thatcher in his 1994 film Tracking Down Maggie.

This mid-career style – initially born from being demoted from cinematographer and to keep the crew size to a minimum – was made famous in films such as The Leader, His Driver and the Driver’s Wife, about the South African nationalist Eugène Ney Terre’Blanche, Kurt and Courtney, about Kurt Cobain’s death and Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madam, about a Hollywood prostitution ring. This style still rears its head from time to time, such as in the 2011 political film Sarah Palin: You Betcha! But Broomfield is becoming increasingly synonymous with an ever changing, ever evolving aesthetic style, often moving from documentary to drama to docu-drama.

His latest film is an archive-heavy project, showing large chunks of previously unseen footage, as well as spending time with many people close to Whitney Houston, such as friends, her bodyguards and personal tour crew. The film is a sad tale, exploring a troubled life of an artist that came from the hood, made good – but rarely on her own terms - and then sadly burnt out and died at the young age of 48. Here Broomfield talks about the film and the emotional impact it had on him making it.

What drew you to Whitney Houston as a subject?

I knew very little about Whitney but I thought she would make a great story and I probably knew what everyone else knew, which was that she had an amazing voice, she made a lot of people happy, she was incredibly beautiful and that towards the end of her life everyone turned on her and she was judged for being a drug addict and that a lot of jokes were made at her expense because of her relationship to Bobby Brown. I just thought that she was an amazing story and that there must be more to it. Normally I don't know too much about subjects when I go into them and I certainly knew less about Whitney than most of the other films I’ve done.

How was the experience of getting to know her through film?

For me it was an amazing experience but initially I was worried I was going to be making a negative film about a diva that was impossible to work with and all the rest of it. Slowly, both my editor and me fell in love with Whitney because she was such a generous, kind and fun-loving person who was very unpretentious. I think she was generous to a fault, she gave away so much of her money to support her friends and family and their friends and family. Instead of pushing them all away she carried on supporting them and they all demanded an amazing amount from her. The thing is, if you come from somewhere like Newark, New Jersey, somewhere like a ghetto, you're everybody's way out of there, you're everybody's meal ticket. Her family were very negligent in looking after Whitney, not dealing with reports from bodyguard's indicating that there was a big drug problem and so on.

How have you found dealing with her family and estate yourself making this film?

They've been very difficult, they tried to get Showtime to pull out. They made life difficult and would email people telling them not to take part in the film. They were just pretty difficult one way or another, uncooperative and have tried to bring out lots of lawsuits since the film has been finished – none of which has been successful, of course, but it takes up a lot of your time. I had a great team on this film, when I made films like Kurt and Courtney [which Love threatened with lawsuits] I didn't have a great team, so it was much worse because when you're dealing with lawsuits you don't want to be all alone.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Have they been difficult because they are currently working on another film about Whitney with Kevin McDonald and they want to control the narrative?

I think they want to control the narrative and they also want to make lots of money. I think what's disappointing about the family and the estate is that they've sold off all of Whitney's clothes and awards, even her credit cards and hotel room keys. They just auctioned it all off. They even tried to auction off her Emmys. They published books and did a reality show within a year that she died, all very opportunistic. I think a lot of people ended up speaking to me because they felt so angry and felt so let down. I think with her family it's all to do with money. It will be interesting to see what their film comes up with.

As in this one, in a lot of your films over the years the central character is often dead or if alive is unattainable. Is there part of you that relishes the challenge of working around this?

I've made a lot of films, so there's always a few that will support a theory but I don't think this has been the case so much. I think to a certain extent I’ve wanted to make quite iconic films about iconic people and to review their legacies and their lives. It's an interesting question because I suppose people become more iconic when they die and if you want to make something definitive about them there is that possibility because you have this overview of their entire career and life. Which may sound morbid but it makes sense. Although I would say the Biggie and Tupac and the Kurt and Courtney films were more investigations into their deaths, this is the first time I’ve made a film this way.

You've explored quite a few areas of the music industry now, including this film and the previously mentioned music documentaries. What thoughts has it left you with about that world?

I was surprised how candid the guys from Arista [Whitney's record label] were and how illuminating they were. They were all from the then black division of the label and they were all R&B and gospel guys who were responsible for crossing Whitney over into someone acceptable to a mass white audience. I think within the record label and the industry, there was a certain amount of guilt with regard to Whitney. She was so young and so impressionable, so malleable. They just thought this is a sweet kid and, of course, like all creations they fall to bits at a certain point. There was a certain guilt they felt with that and I don't think they were surprised that she had a pretty hard time dealing with her life and dealing with the rejection from her own people, especially at the Soul Train awards when she was booed for sounding too white.

That seems to be quite a pinnacle moment in her life.

I really think it was. The interesting thing about Whitney too is that she was never allowed to do her own music. You would think that someone at the level of Whitney Houston, who probably had the greatest voice in the world, that there would have been so many songwriters to have given anything to sing one of her songs. Everybody does that but Whitney never did that, I think that's because the record company maintained such a strong hold over her that they never wanted her to have that kind of independence. So financially, she never benefited from the residual rights because she was always singing other people's material. I think that very much weakened her position and her authority in the industry. Maybe that would have given her the sense of independence and self-determination that she needed because even though she was such a big star and had such power she was ultimately always controlled by other people.

There's a scene in the film in which Whitney Houston and Bobby Brown are acting out the cake scene from the Ike and Tina Turner film What’s Love Got To Do With It. Which given the allegations of domestic abuse in that relationship, I found quite a bizarre scene to watch. What were your thoughts on that area of things?

Yes, there were allegations of domestic abuse but from what I understand, from talking to a lot of people who were around them all, is that it was a very violent group of people. I think people from their particular cultural background in New Jersey, at the time often became quite violent when there was a heated argument. I know that Cissy [Whitney’s mum] beat Robyn [Crawford, Whitney’s closest friend, creative director and, some suggest, gay partner], Robyn beat Bobby, Bobby beat Whitney, Whitney beat Bobby and so it went on. Her brothers had fistfights with Whitney, so it wasn't just Bobby, it was the whole bunch.

I think to have pointed the finger at Bobby would have narrowed looking at their whole issue – which I find tricky to do because we are, of course, privileged white people. I didn't want to be casting aspersions about a whole way of being but I think that's the reality, that there was a lot of violence. I had David Roberts, Whitney's bodyguard, talking about Cissy smashing up John Houston's [Whitney’s father] car with a big stick. There was a lot of violence in that group to demonstrate their emotions about things. I don't think by any means it was just Bobby.

Whitney’s sexuality is explored quite a bit in the film. What was your intention and motivation for doing this?

I think my intention was to show that there was this very strong, very positive, very creative relationship between these two people, Robyn and Whitney, and that in many ways Robyn was Whitney's guardian angel and they had an amazing bond, creative, emotional and otherwise. Yes, I do believe they had a gay relationship but I think far more important and far more interesting was the depth of their relationship, that they obviously deeply loved each other and when Robyn left things went to pieces. It's been interesting because some of the tabloids have been saying that the film confirms Whitney was gay, rather than looking at the relationship and saying, 'this is an amazing relationship' and that's the way I think we should be looking at relationships. Is it a great, supportive, nurturing, wonderful relationship or is it a destructive one? What's the obsession with whether someone is gay or not?

What’s been the biggest take-away for you in making this film?

Being able to give Whitney a voice, I think. For a long time the film wasn't working. I changed editors part way through, as initially you didn't feel the emotion of Whitney, it wasn't really her film. We had very little of her talking and we didn't really understand where her head was at any point in her life. Mark [the editor] and I were often tearing up in the editing room and I thought, ‘what's going on am I getting feeble or something?’ You really feel her, you feel her pain, her love, her intensity. When she becomes so misunderstood and so judged, you're in pieces.

Given the emotional nature of her story and the film. Is Whitney someone you've struggled to get out of your mind after the film has finished?

I had to exercise Whitney from my mind. She was really interfering with my sleep. Most of my editing seemed to happen between 3-7am in my head. It was driving me nuts because I wasn't sleeping and this went on for a while. When we finished the film I would just go on these incredibly long bikes rides for four or five hours, day after day and then I’d be so tired at the end of the day that I would just pass out. I did that for about three weeks.

You have a habit of returning to characters or stories to make a second film about them. Is there anyone from your previous films that are still niggling away at you that you’d like to return to?

Not really, I don’t think so.

Given Trump is now in office, if we saw the return of Sarah Palin to front-line politics, would that not interest you?

Oh god, that was such an awful film to make. That film was such a pain and it never really got better. People often say, ‘why don't you do a film about Trump?’ and I think it would be fascinating to do a great film about his first 100 days but you certainly wouldn't get access so it would be one of those films in which you're just tormenting yourself.

'Whitney: Can I Be Me', a film by Nick Broomfield and Rudi Dolezal, is in cinemas 16 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments