Happy End: The secret kindness of Michael Haneke

The Austrian director is responsible for some of cinema’s cruellest cuts. But was the tenderness that’s now more obvious in his work always there?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Michael Haneke is the most jovial director I’ve met. Just as boxers and horror writers get their anger and angst out in their work, often surprising those who meet them with their well-adjusted dispositions, so it is with the Austrian responsible for some of cinema’s cruellest cuts.

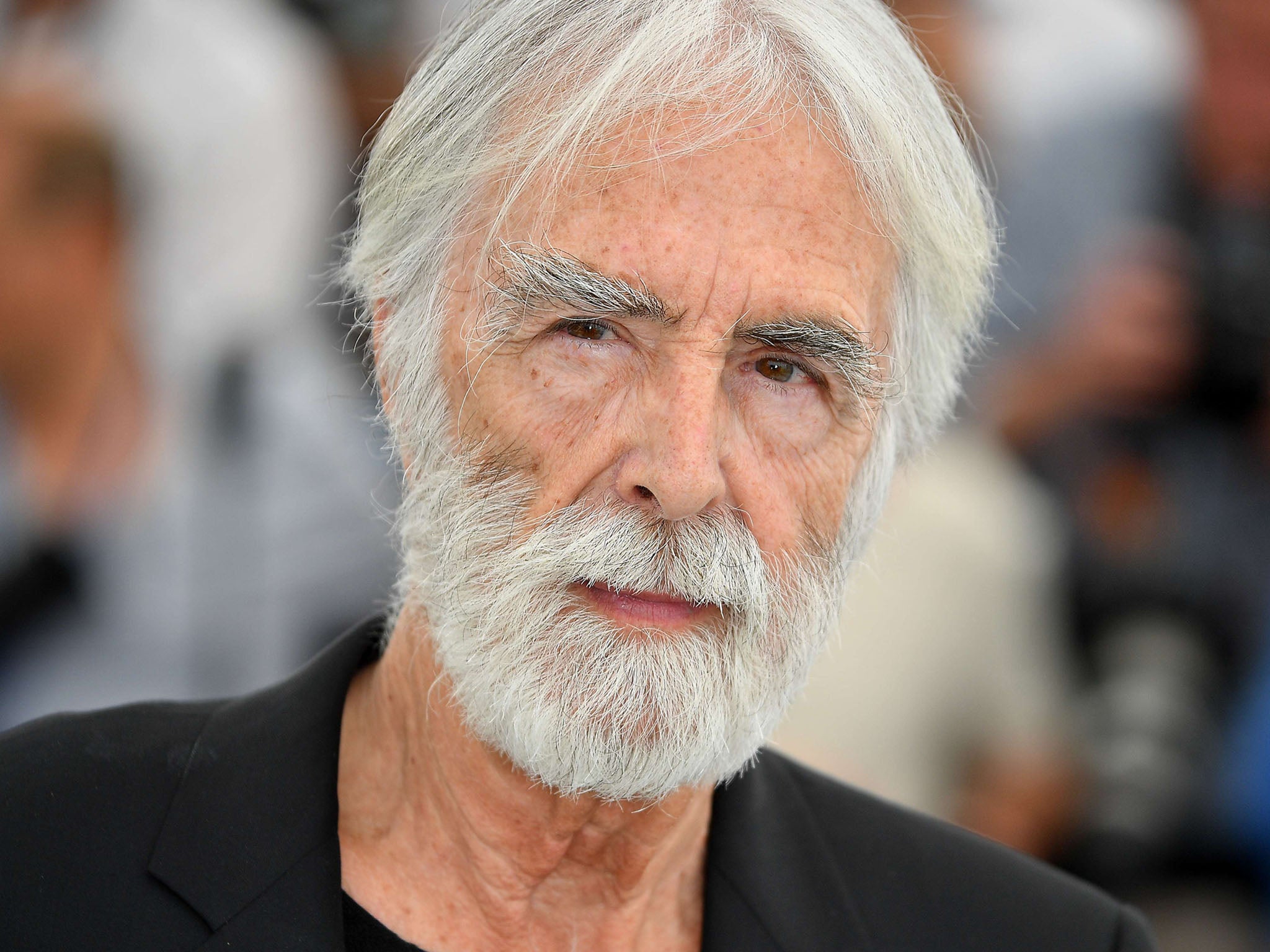

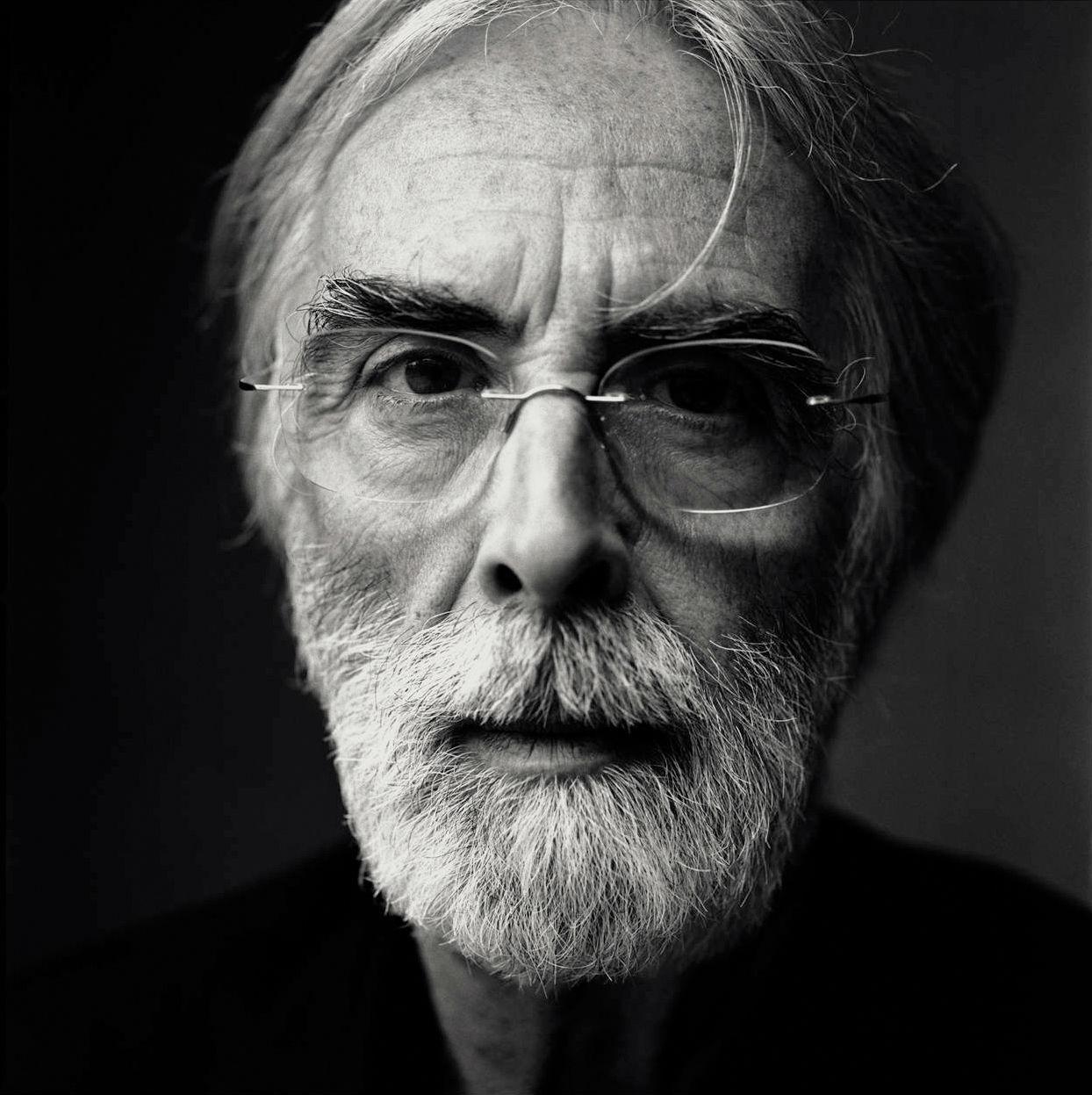

The 75-year-old may be the last giant standing (occasional Godard transmissions aside) in the tradition of the austere European auteur. That reputation is enhanced by his new film, Happy End, in which Isabelle Huppert’s bourgeois Laurent family have their hypocrisies teased out with a sharp scalpel. Yet Haneke’s laugh is an actual ho-ho, as he conspiratorially discusses answers in German with a translator. He’s dressed mostly in black, and his beard is white, but a grey scarf is flicked over his shoulder with the raffishness of an Oxford don.

Haneke was born in Germany in 1942 and raised in post-war Austria by actor parents. In his teens he admired the new, alienated Hollywood heroes James Dean and Marlon Brando, but his course was set when he saw Pasolini’s sadomasochist, scatological provocation set in Mussolini’s rump fascist state, Salo (1975). It left him “sick for three weeks”, and wanting to leave his own future audiences similarly, usefully traumatised, till they had to tear their wounded gaze away.

He achieved this with his breakthrough, Funny Games (1997), about a woman who is being tortured after a home invasion bravely escapes, only for one of her captors to press the video rewind, fixing his mistake and her fate. That brutal switch typed Haneke as cinema’s cruel scientist, replacing Hollywood consolations with merciless hurt. From the crucified bird in his Palmes d’Or-winning investigation of the proto-Nazi atmosphere in a small German town in 1913, The White Ribbon (2009), to Juliette Binoche screaming as she suddenly sees her little boy teetering on a high, distant ledge in Code Unknown (2000), you take your seat for Haneke in the brace position.

But you shouldn’t always take a director at his word. His Cannes Grand Prix-winner The Piano Teacher (2001) gave Isabelle Huppert a role as iconoclastic as Elle, playing an academic whose icy control repressed deep masochistic pain. She’s left beaten up and humiliated, and responsible for savage violence of her own. But Huppert and Haneke bring you so close to this sometimes repellent woman that you absorb her pained humanity.

Haneke the former psychology student “loathes” giving his characters the easy explanation of psychological pasts. Huppert filled her performance with acute, daring psychological leaps anyway. The director, meanwhile, pushed her past acting to more visceral truth, as when her elbows involuntarily jerk up like bird wings, as she fights in bed with her mother. “That’s what he was looking for – something you can’t control,” she recalled.

Funny Games’ rewind rupture typified Haneke’s early desire to tell audiences they’re watching fiction. But the great actors he loves make these worlds real, despite him. His most popular film, the Palmes d’Or and Oscar-winning Amour (2012), played more like Hitchcock horror than Hollywood weepie, in showing the suffering love of Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva’s elderly couple as the latter succumbs to dementia. Yet Haneke’s tenderness to them is plain. “I’m trying to be less theoretical,” he told Sight & Sound. “A film like [1989 debut] The Seventh Continent wasn’t a realistic film; it was a model ... [Amour] is hopefully ... getting closer to life.”

It’s not only Amour that shows Haneke’s love for humanity. His vision of apocalyptic social breakdown among the French countryside’s second homes, Time of the Wolf (2003), starts with a boy’s dad being callously shot dead, but ends with that boy saved from fiery suicide in the arms of a stranger. Juliette Binoche’s frightening humiliation by two young men on the metro in Code Unknown is almost unbearable to watch because Haneke cares for her.

Happy End dissects an unhappy, self-deceiving family. And yet Jean-Louis Trintignant, as a patriarch this time slipping into dementia himself, has a beautifully intimate conversation with his 12-year-old granddaughter Eve (Fantine Harduin). Even if, this still being Haneke, she’s probably a murderer, and their heart to heart is about poison and suicide. “He’s a more humanistic director than he seems,” Huppert has noted. “There is of course no sentimentality, but there is a belief in mankind.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“I always say I’m a realist,” Haneke tells me. “But of course that’s not enough in itself. You have to have hope in your private life, or in society – if you’re a pessimist, it’s a useless thing to be. But just hoping is insufficient. You have to believe that you can move people, or change people, or making the works would be completely useless. All artists are bound to believe in that.”

Was the tenderness that’s now more obvious in his work always there, with its apparent cruelty coming from a place of kindness towards his characters?

“I am full of kindness!” he chortles.

The skewerer of bourgeois callousness – allowed by careful distance from their victims in Happy End; when a Laurent meets one on a housing estate, he gets a kicking – is also less austere in private than his films sometimes suggest. Not put off by the murders that holiday homes inevitably attract in his work, he has a weekend place in hilly countryside in Lower Austria. Glimpses of rural France in Time of the Wolf, or sunny Calais in Happy End, are no less lovely for their irony. Does he have the appreciation associated with Germanic artists for the romantic and sublime in such landscapes?

“It’s for the audience to decide if it’s in my films. But I can’t deny that I have a certain weakness for beautiful things – be it in landscape, be it in interior design. Yes, most definitely. But surely that’s something that most artists who work in the visual media would have? Because otherwise, if you’re a film-maker, you’d be in the wrong job.”

There are themes which run true from The Seventh Continent to Happy End. “Suicide without end!” Haneke laughs. That’s certainly one. The watchful, contemplative child in his first film is also matched by Fantine Harduin’s enigmatic role here. Both have unusually deep, unspoken inner lives. “I was a loner as a kid, and I’ve remained that way,” Haneke once told Film Comment. Do his films’ children watch the world as the boy Michael did?

“Probably yes,” he says, “but I’m not sure I can remember too well. Children probably have to be attentive, because they’re the weakest link in the hierarchy. For that reason they’re particularly fascinating and productive in relation to violence. The same would go for some extent to women in our society. And at the bottom of the hierarchy you have animals. Which is why so many animals get killed in my films.”

Women and children aren’t always the vulnerable ones, though. Watch Happy End carefully, and at the back of an already long shot, like a sight gag, you’ll see a woman and pram shove an old couple off the pavement. This may be the most personal scene in the film. “Yes,” Haneke laughs with feeling. “I’ve experienced this myself, and I absolutely hate these women with their buggies, who push their way through like ramrods! I hate it!”

Happy End begins with Harduin in a jarring, jittery Snapchat sequence. It continues Haneke’s career-long interest in our technological lives.

“Yes it is indeed fascinating, Snapchat,” he considers. “The internet has to some extent taken on the role of the church. Earlier, somebody would have gone to a priest and confessed their sins, and they would be told to recite ten ‘Our Fathers’, and that would lead to salvation. Now, we turn to an internet forum instead. I looked at dozens of these pages of confession in preparation for the film, and it was completely astonishing. I think if a priest had had a tape recorder, he would have ended up with a very similar result.”

From the TV static that ends The Seventh Continent through Funny Games’ video nasty to a Snapchat confession, Haneke has chronicled a clear evolution. “The development of social media is extraordinary,” he considers. “It’s unique in humankind for an extreme change of that kind to happen with such speed, and obviously no one now can do without these technologies at all. My main fear isn’t the amount of time people spend looking at their mobile screens. It’s if the electricity fails. There’d be no food, drink, heat. That would be the complete end of all of us, something I predicted in Time of the Wolf.”

Happy End’s family live largely oblivious to their refugee neighbours in Calais, the latest example of the insensitivity described a favourite poem of Haneke’s, by Brecht: “A smooth forehead suggests insensitivity. The man who laughs/Has simply not yet had the terrible news.” Haneke himself mostly leaves refugees in the film’s margins, till they intrude at a wedding party like the return of the repressed. “The film isn’t about migrants,” he explains, “it’s about us.”

The repercussions of a scuffle between migrants on a Paris street at Code Unknown’s start were developed with Juliette Binoche, again, in Hidden (2005), which is rooted in France’s colonial past in Algiers, and 1961 massacre of Algerians in Paris. “We wouldn’t have the terrorism that we have,” he says, “if it wasn’t for colonialism.” A prescient theme barely altered for Haneke by 9/11 only gets more timely.

“It’s a North-South conflict,” he says. “The rich countries against the poor. That’s been confirmed categorically, since Code Unknown. Refugees aren’t a simple problem, and there are no simple solutions, but a solution has to be found. The problem is that, for a lot of people at the moment, the solution is a shift to the right. I’m especially sceptical of comparisons with the 1930s. But this current atmosphere, with everyone dancing on the edge of the volcano, has a parallel there. Because in my youth, immediately after the war, everybody thought that things would get better – because everything could only get better, after that. But now everybody thinks that things can only get worse, and that is a parallel to the situation before World War Two.”

I wonder if Haneke is treated as a public intellectual in Austria, being asked this sort of stuff all the time.

“Yeah, you do get asked those things,” he says, “but I’m not the kind of person who has a public opinion on everything when asked. I have colleagues who do that, and respond to every possible fart!” he laughs. And what is German for “fart”, Herr Haneke? “Furz!” Thus the worlds of Michael Haneke and Viz comic briefly meet.

The reserve that is more characteristic of Haneke onscreen is typified by 86-year-old Jean-Louis Trintignant’s return for Happy End. There’s a cold nobility to his features, a distance present even when he was the handsome young star of My Night At Maud’s (1969).

“That’s because he always has something secret about him,” Haneke explains, in words that could apply to his own films. “That’s what makes a great actor. Another example would be Marlon Brando. He has that same kind of secret. They never play it fully. They always stay back just a little bit. And that is precisely what transports the thing that’s otherwise inexpressible.”

Haneke is at his most elegant in Happy End, where he tried “to cut back as much as possible”. This refining of technique suits a provocateur who has survived to be cinema’s Old Master. Such rigour had one example in a stepfather with “an absolutely pitch-perfect ear”, he told Sight & Sound, who would “wince in pain” at a false note. There are other youthful traces, too, from a Protestant upbringing in Catholic Austria. Though he lost his faith, something lingered.

“Well certainly so, yes – at 14 I wanted to be a priest. And people with bad intent say to me that’s what I still want to be!” Haneke laughs, before clarifying. “Not a Catholic priest. A pastor – a vicar.” You can certainly imagine the almost reverend Haneke peering down from some rural pulpit. He has been kinder to his cinema flock than we realised.

‘Happy End’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments