‘Honestly, I wish I could make films less connected to myself’: One Fine Morning director Mia Hansen-Løve on life spilling into fiction

The French filmmaker speaks with Annabel Nugent about her new film starring Léa Seydoux, what it means to be both a mother and a filmmaker – and the myth about directors that she won’t buy into

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On some basic level, Mia Hansen-Løve makes movies because she has a “very, very bad” memory. “It’s a way to hold on to events that I want to remember, to really make sure the things that matter to me will still exist even if I forget them,” says the French filmmaker. She scrunches up the already rumpled tissue in her lap and releases it again. “I’m always worried that I will forget everything.” That fear goes a long way in explaining the many parallels that exist between Hansen-Løve’s real life and the lives explored on screen in her emotionally intense, often award-winning films.

Hansen-Løve was only 23 when she wrote her debut All Is Forgiven; 25 when she directed it. The film, nominated for Best First Feature at the 2008 César Awards (the French equivalent of the Oscars), was loosely inspired by her uncle and cousin. Goodbye First Love (2011) told of a feverish romance that looked not unlike her own with the director Olivier Assayas. The same could be said – although Hansen-Løve herself has not said it – of her English-language debut Bergman Island, released last June and written the year that she and Assayas split up. Likewise, the DJ in Eden (2015) was inspired by her brother, while the philosopher in Things to Come (2016) was based on her mother. This time around, it’s her father to whom she is indebted.

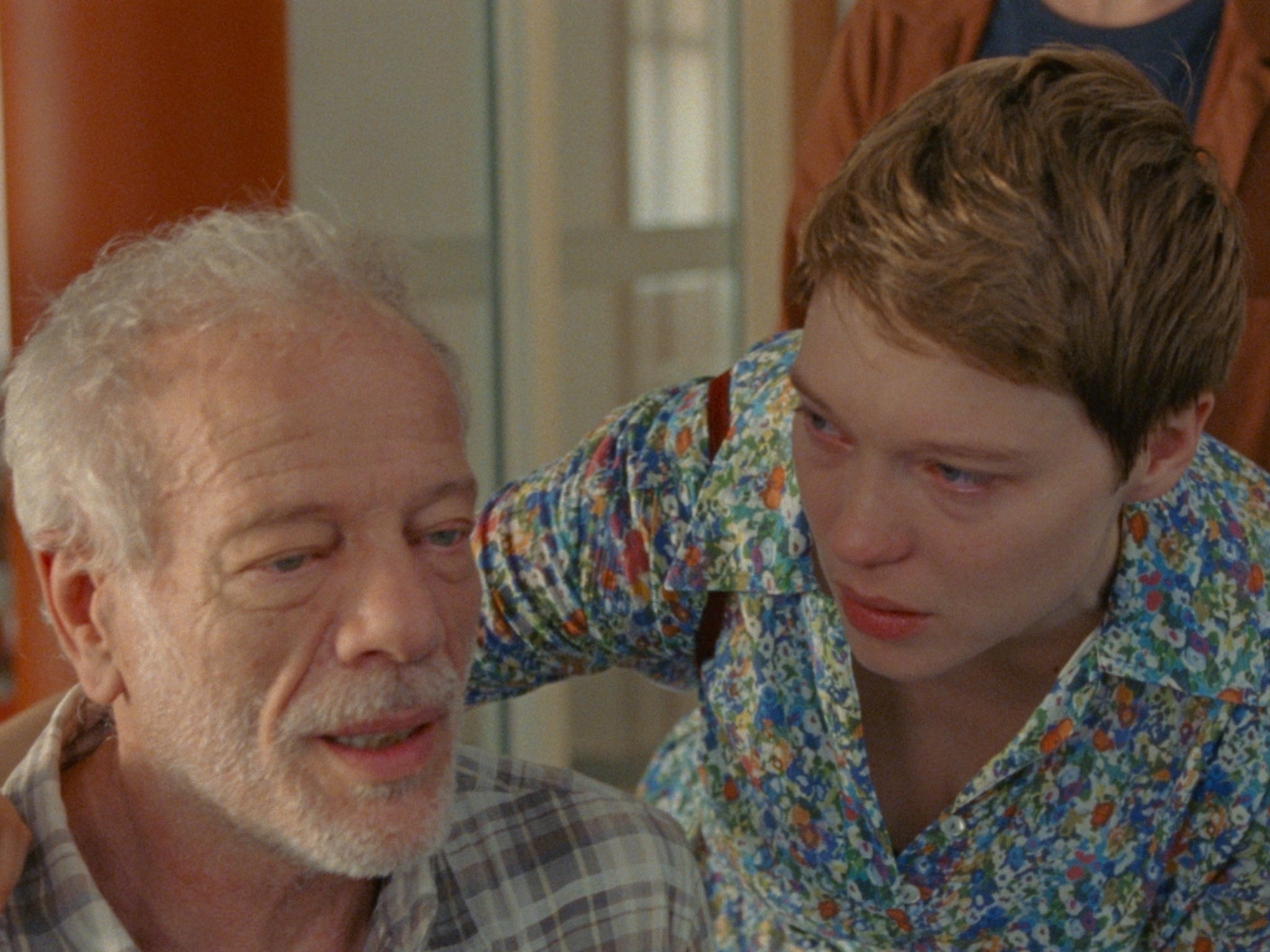

Now 42, Hansen-Løve has always felt compelled to wade knee-deep in the murky waters of her past, swishing sand and gravel to find glinting specks in her pan. The latest speck is One Fine Morning. Her film stars No Time to Die’s Léa Seydoux as Sandra, a translator and single mother who is caring for her ailing father (Pascal Greggory) when she starts up a romance with an old friend (Melvil Poupaud). It’s a story that mirrors the period in Hansen-Løve’s own life during which she fell in love with her current partner, filmmaker Laurent Perreau (a dead ringer for Poupaud, in fact), all the while witnessing her father succumb to Benson’s syndrome, a variant of Alzheimer’s. This vertigo of feeling – delayed grief and new love – is at the film’s heart. “It is my depiction of what it was like to feel those very contradictory emotions,” she says, adding that more often than not, that’s how life goes. “It’s never just one thing.” Her father died two months after she finished the script, around the same time that Hansen-Løve discovered she was pregnant.

A Mia Hansen-Løve film strolls along to an everyday beat, cigarette lolling from its mouth. Achieving naturalism is a painstaking process in itself, though – something her actors can personally attest to. As a filmmaker, Hansen-Løve is often described as exacting. A lot of time was spent, for example, showing Greggory how to precisely replicate her father’s walk: the degree of his stoop and the weight of his gait. “I tortured Pascal a little bit – but as an actor, I think he likes it,” she laughs. As if on cue, she plucks a near-invisible stray blonde hair off her fuzzy jumper.

As well as having a reputation for precision, Hansen-Løve has been known to form strong connections with her female stars. Seydoux and Vicky Krieps (of Bergman Island) have praised her approach. For her part, Hansen-Løve is quick to clarify that she has had “very nice and strong relationships” with her male actors, too. “The world doesn’t divide for me between women and men – fortunately not – but it is true that I have had very strong connections with many of the actresses in my films.” It comes down to trust. “There is this myth, which is grounded in reality, of the very harsh director – and often it’s male directors, but it can be female as well – who creates conflict with the actors to try and get the best result out of them.” Hansen-Løve does not subscribe to this myth. “I’ve always believed a trusting, respectful relationship will lead to better performances – and to be fair, up until now that’s usually true.”

In conversation, Hansen-Løve is amiable and easy. Ask her if she is ever bothered by the probing questions that the personal subject matter of her films inevitably invites, and she’ll shrug. “Honestly, I wish I could make films less connected to myself, so I wouldn’t have to talk about it so directly, but those are the films I write, so I feel I have to accept it really,” she says. “I stand by it – and I’m so out of the limelight, it’s not like it would feed the tabloids. The only people who will be interested are cinephiles.” And conversely, does anyone in her life mind being dramatised on screen? “Maybe my mother could have reason to be concerned,” answers Hansen-Løve, “because she comes up so often in my films; but she has been the greatest supporter of my work, and I think she enjoyed being played by Isabelle Huppert so much that she’s fine with all of it.”

For years, Hansen-Løve was linked to Assayas, the director behind the 1996 cult classic Irma Vep. Not only romantically (they were together for 15 years and share a 13-year-old daughter), but professionally, too. Her career in the industry began as a teenager in his movies, after she auditioned for the 1998 film Late August, Early September. But to call her a former actor, she says, is a stretch – and possibly, from the sounds of it, an annoyance. “I never really was an actress,” says Hansen-Løve. “And actually I find it interesting how often I am reminded of it. It’s weird to me because in the end, my career as an actress is, like, 14 days of shooting, whereas I have made eight films and have 20 years of experience as a director now, but still I’m an actress-turned-director.” She pauses, “I wonder if this is because I’m a woman... If I was a man who spent 14 days shooting as a teenager, would I be reminded as often?”

Her previous film, Bergman Island, was shot in the Fåro Islands, home to the late Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman. It stars Krieps and Tim Roth as a screenwriter couple on a writing retreat, whose relationship is on the rocks. Questions of motherhood swirl around the film, as Krieps’s character struggles to reconcile her love of Bergman’s work with his personal failings as a parent. Bergman was a father to nine children, all of whom he largely ignored in his lifetime. “When you’re a director and you have kids, you have to deal with these questions all the time,” says Hansen-Løve, a huge Bergman fan. “I wasn’t trying to judge him for his choices, or criticise them. In fact, I don’t really care. I was saying that as a woman I couldn’t do what Bergman did, which was make loads of films while having nine kids that he basically had raised by various nannies and women. What I wanted was to explore what it is for a woman to attempt to be both a filmmaker and a mother – because physically, emotionally, I couldn’t leave my kids that long, so I couldn’t make that many films. How do I make the best of that?”

Happily, Hansen-Løve has found that her children add to her work infinitely more than they take away. “The bond I have with my kids actually feeds my work and creates more depth in my films, a sensibility you may not find in films made by men – including Bergman,” she says. “Very rarely does Bergman approach that relationship, but in films made by women – especially those who are close with their children – there can be a depth created that you may not find with male directors as much.”

After Bergman Island, with its international actors and faraway location, Hansen-Løve wanted to return home to Paris. “I felt I had to focus on things that were closer to my everyday experience,” she says. In filming One Fine Morning, Hansen-Løve returned to all her past haunts: her old neighbourhood, her father’s nursing home, her grandmother’s apartment. “I would never have gone back if it wasn’t for this,” she says. “I would have rather forgotten them. But because it is a film, it’s actually fun. It turns something that was tragic and painful to live through into this childish game.” The actors, she says, bring with them some distance. “I can remove some of the drama in myself by transferring it onto the screen. It helps mellow the sense of drama within you, and in a way, you can get rid of it.”

‘One Fine Morning’ is in UK cinemas now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments