I lost a husband and a brother – but they live on in Merchant Ivory’s golden years

It is 40 years since ‘A Room with a View’ made James Ivory and Ismail Merchant into household names and their work a byword for cinematic elegance. Here, Sarah Sands reflects on the halcyon years when her then husband Julian Sands and her brother were both at the centre of a world of luscious longing and tenderness

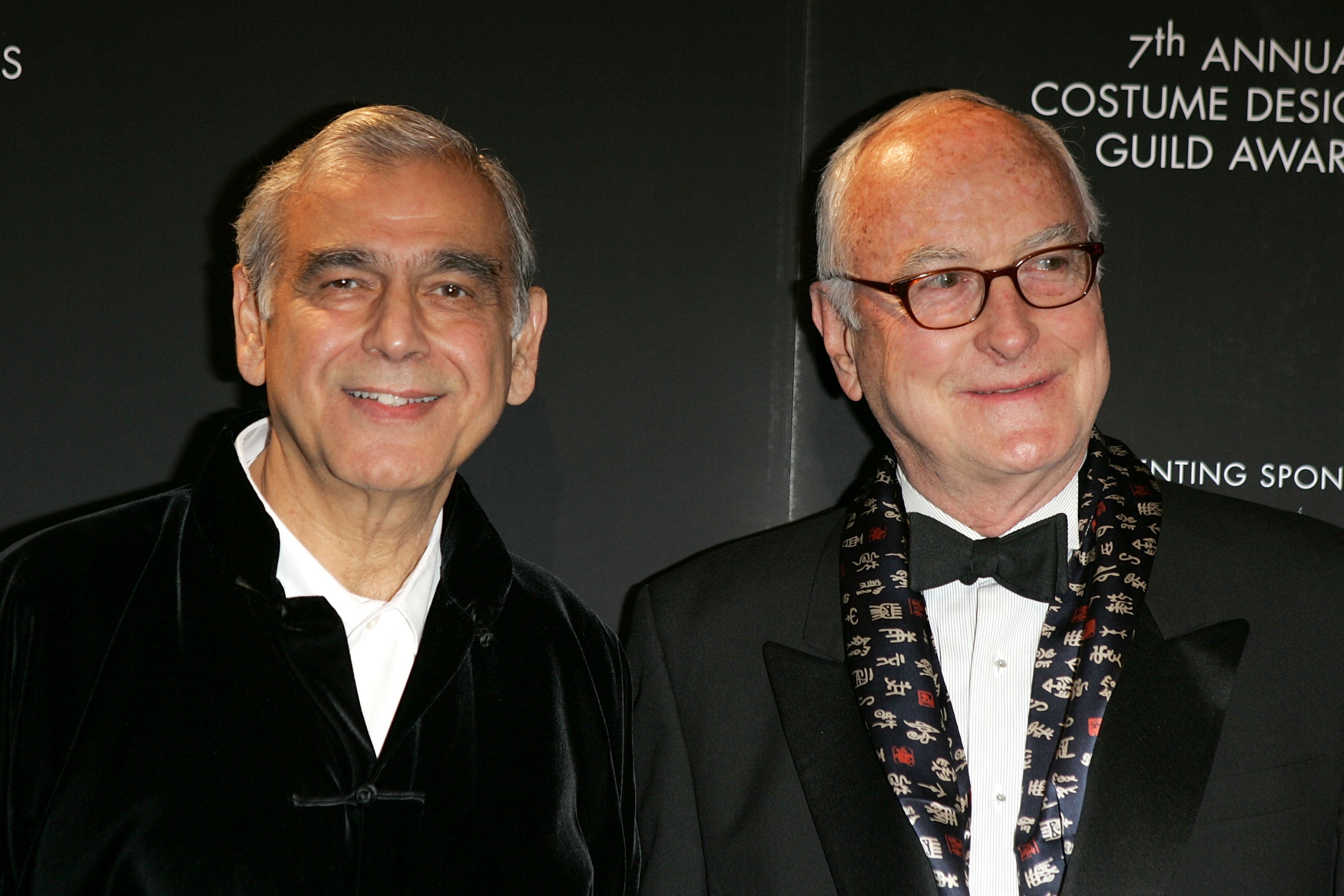

On Wednesday 20 November, the Curzon Mayfair will host a gala screening of Merchant Ivory, a masterful feature documentary directed by Stephen Soucy. Both on screen and in the audience will be some of the most prominent names in British acting history, including Helena Bonham Carter and Emma Thompson; actors who all rose to fame because of the relationship between the quiet, elegant director James Ivory and the flamboyant producer Ismail Merchant.

Bonham Carter, who anchors the documentary tracing her ascent from ingénue to national treasure, looks back with mischief and pleasure. “It all reads like a novel,” she says. And so it does. In both art and life, the duo adapted novels by authors such as EM Forster, Henry James, and Kazuo Ishiguro, creating works renowned for their luscious expressions of suppression, pain, longing, and tenderness.

Rupert Graves, who appeared in the two Merchant Ivory films I know best, A Room with a View and Maurice, tells the documentary makers that, ultimately, these films were about how you should live your life.

The film takes the form of a retrospective of James, who, wise and humorous at 96 years old, has long outlived Ismail, who passed away at the age of 68 in 2005. Their story, like their films, is a tale of both loss and triumph.

James reflects on his 40-year love affair with Ismail, which was understood but never publicly discussed – because that was simply how things were. They never spoke about their relationship with their families.

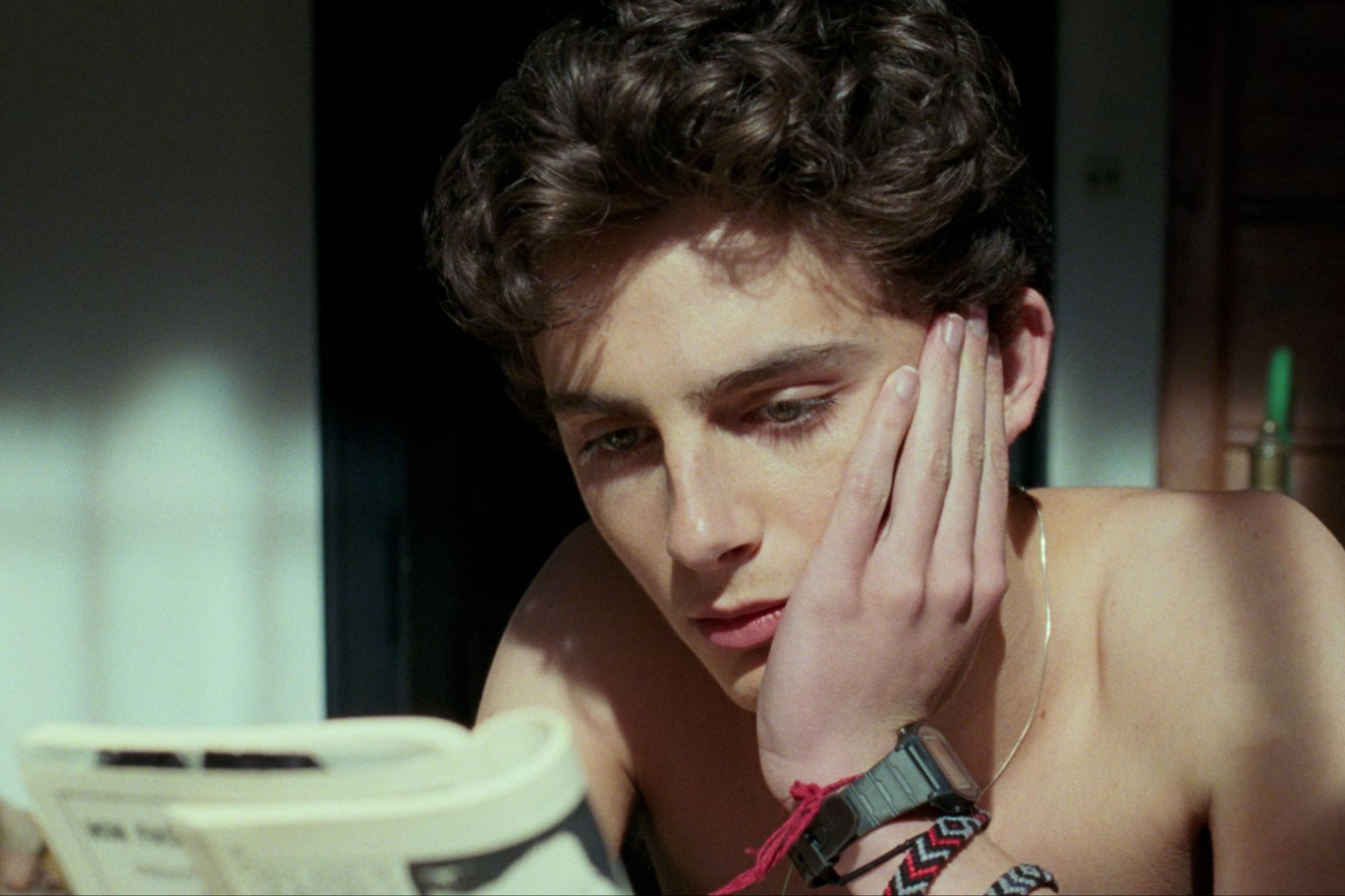

In 2018, at the age of 89, James won an Academy Award for his screenplay of Call Me By Your Name, a story of a young man’s coming-of-age gay love. James recalls that people in New York would stop him to shake his hand and tell him he had changed their lives – not because of Call Me By Your Name, but because of Maurice, a film he had made much earlier, in 1987.

That novel, written by EM Forster in 1913, was not published until 1971, after Forster’s death. The screenplay was written by my brother, Kit Hesketh-Harvey, and the film starred Hugh Grant in one of his first roles alongside James Wilby, who would later appear in Gosford Park.

Kit took on the project because James’s usual collaborator, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, felt that the world of a gay love story between two Cambridge undergraduates in Edwardian England was too unfamiliar to her.

Meanwhile, Wilby only accepted the role after Julian Sands walked out of the film. As Simon Callow notes in the documentary, Merchant Ivory were both filmmakers and family, with all the associated dramas and arguments.

They went on to make bigger and more ambitious films, notably Howards End and The Remains of the Day, featuring memorable performances by Emma Thompson and Anthony Hopkins. Yet, the tension between passion and restraint we saw in those films had already been well established in A Room with a View and Maurice.

In the documentary, Vanessa Redgrave sighs rapturously about the early Merchant Ivory films: “Oh, those were the days.” And indeed, they were.

The documentary opens with the theme music to A Room with a View, Puccini’s “O mio babbino caro”. The audience is transported back to 1985, to the hills of Tuscany humming with a passion for life that defied convention. The film’s casting was superb throughout – Maggie Smith, Denholm Elliott, Daniel Day-Lewis – but it was Sands, my then husband, who truly embodied the character of George Emerson.

Julian was a Yorkshire boy with a strong, stocky frame but chiselled cheekbones and a delicate mouth. We met when he was at drama school and there was always an element of the chameleon about him: a scholarship boy at a southern public school who could imitate the manners of Forster’s Honeychurch family, but who was most himself when clambering over hills with his Yorkshire brothers, Jeremy, Robin, Nick and Quentin. We married young, and by the time Julian was cast in A Room with a View, I was 23 and pregnant with our son.

Those days were halcyon. I loved the wry precision of James and the galvanising energy of Ismail. Julian introduced my brother Kit to his friend, musical writer Julian Slade, and Kit later staged a production of Slade’s most famous work, Salad Days, about young hopefuls embarking on adult life. A line from the show has always stayed with me: “We mustn’t say these were our happiest days, but our happiest days so far.”

A Room with a View caught everyone by surprise – an arthouse blockbuster that captured the popular imagination. As Callow recalls in the documentary, students began throwing Room with a View parties. The kiss between Julian and Helena Bonham Carter became a poster for heaving-hearted teenagers. Even Thompson admits, “Of course, I fell heavily in love with Julian Sands.”

Following the film’s success, Julian was billed to star in the next Merchant Ivory project, Maurice. According to the documentary, Ismail had grave doubts about making it but James was determined and asked Kit to write the screenplay.

Wilby and Grant then recall Julian’s sudden and inexplicable departure. Wilby says Julian simply announced, at the Venice Film Festival, that he was leaving the Merchant Ivory family, his agent, and his wife.

I recall it happening in that order. At the time, I was heartbroken and returned to our flat in South Kensington with our one-year-old son.

Over time, though, I came to appreciate that lives don’t always unfold as expected, and alternative futures can also be rosy. Julian moved to Los Angeles, met his future wife Evgenia (whom I liked), and had a long, happy marriage with two beautiful daughters, Natalya and Imogen.

I later met my future husband Kim, a former editor of The Independent on Sunday. Together, we raised three children: Henry, my son with Julian, now 37; Rafe, 31; and Tilly, 29.

I last saw Julian at my father’s funeral in 2022, where I joked about his grandmother’s pride when he was earning £300 a week and owned a Crombie overcoat. Our mutual friend, and Henry’s godfather, John Malkovich, said of Julian: “His great gift was to make life much more interesting.” Like George Emerson, Julian embodied colour, curiosity, and courage.

Julian died in January 2023, lost in a whiteout on a mountain in LA. My brother Kit died suddenly two weeks later from heart failure. Seeing Julian so alive in footage featured in the documentary, and knowing how close Kit remained to James, makes it all feel bittersweet; an experience tinged with melancholy and loss.

When Kit died, he had James’s autobiography by his bedside and had planned a trip to New York to see him. In the documentary, there’s a poignant moment where Kit’s voice breaks as he describes seeing James after Ismail’s death. James had wandered into six lanes of traffic in New York, seemingly in a trance, overcome by grief. Kit recalled dragging him away and asking what he was doing. James explained that while he had understood the emotional effects of grief, he hadn’t anticipated its physical toll. Ismail was the love of his life.

The film ends with a dedication to my brother Kit. Out of all Merchant Ivory’s films, I am so proud that he made Maurice. James reflects on gay friends now in their sixties who have led romantically uneventful lives, and he feels sorry for them. Watching Anthony Hopkins in The Remains of the Day, brushing away the possibility of passion, I am grateful that others now have the freedom to choose how they live.

‘Merchant Ivory’, directed by Stephen Soucy, is on general release this December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments