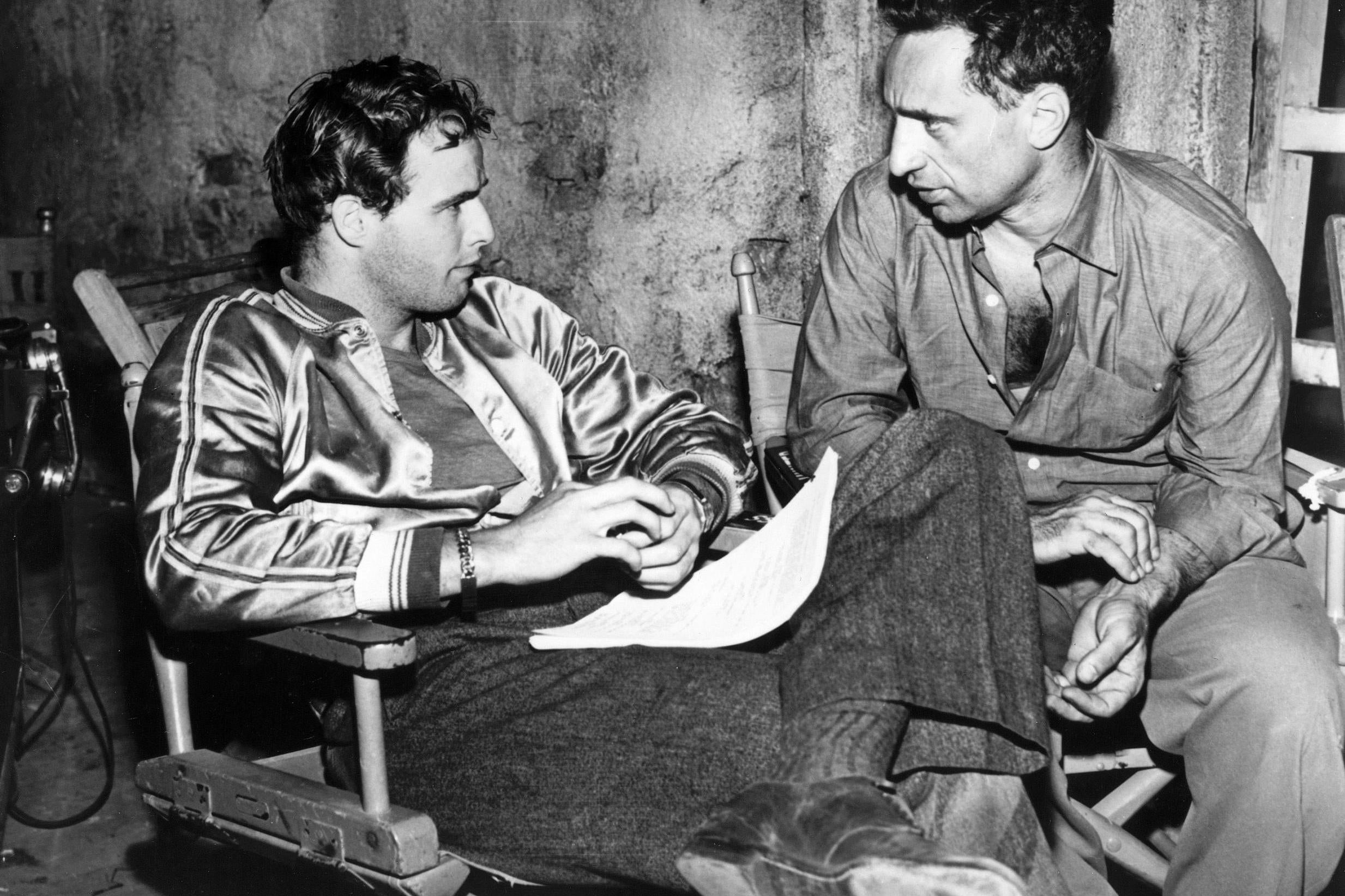

Marlon Brando and Elia Kazan brought out the best in each other – but did it end because of money or to avoid an anti-climax?

Ahead of the re-release of ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ next month, Geoffrey Macnab examines one of Hollywood’s most influential actor-director partnerships

They are two of the towering figures of 20th-century American cinema. They did exceptional work without each other and yet, if their paths had never crossed, their reputations would surely be much diminished. They made only three films together, A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), Viva Zapata! (1952) and On The Waterfront (1954), but it’s hard to think of any more influential screen partnerships than that between actor Marlon Brando and director Elia Kazan.

“Marlon I can’t touch now because he costs too much, and I’m not going to pay any silly figure,” Kazan later lamented of how the actor he turned into a major movie star had spiralled out of his price range. Kazan, who is now the subject of a two-month season at London’s BFI Southbank in February and March, died in 2003, Brando a year later. In hindsight, it seems perverse that they didn’t continue a collaboration that was so much to both of their advantages. Nonetheless, their trio of films was exceptional. They had the good fortune to work together when both were at the peak of their powers before Brando had piled on the pounds and Kazan’s reputation began to waver.

There was an element of good fortune in the way their partnership started. Brando, then 22 and a student of acting coach Stella Adler, had performed in a five-minute cameo in a 1946 New York stage production, Truckline Cafe, directed by Harold Clurman and produced by Kazan. Brando had been lucky to get the part. His audition was terrible and he had demanded a huge salary. Kazan had struggled to hear what he had been saying. Nonetheless, there was something about the mumbling, introspective, physically imposing actor that appealed to Clurman.

Brando had made the most of his few minutes on stage. He played a soldier who has just drowned his unfaithful wife. The play, written by Maxwell Anderson, was a disaster, closing after only nine days, but everybody paid attention to Brando’s monologue. “It must be admitted that the opus has a sharp moment or two,” Billboard acknowledged in an otherwise hostile review. “Marlon Brando smacks over a telling scene in the last act as the repentant murderer.” As the word “smack” hints, there was nothing subtle about the actor. He milked the part for all it was worth. Future film critic Pauline Kael who was in the audience, famously thought he was having convulsions.

“A talent scout for one of the major picture companies asked me if Brando wasn’t overacting. I thought: would that all actors could ‘overact’ that way,” Clurman remembered of the performance.

Brando was a fascinating mix of contradictions: a sensitive, introspective and articulate figure who had a genius for playing brutes. He had already turned down a part in Kazan’s Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) when Kazan had given him $20 and sent him off to Provincetown to meet playwright Tennessee Williams, who was to consider him for the role as the macho, belligerent Stanley Kowalski in the stage production of Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire. Brando hadn’t turned up. He’d spent the money for his fare on food. “I figured I’d lost 20 bucks and began to look elsewhere,” Kazan recalled in his autobiography. However, the actor hitchhiked to Provincetown and eventually did meet Williams, three days late.

In theory, Brando wasn’t right for the role at all. He was 23 by then and Williams had written Kowalski as an older man. The young actor was also considered too “pretty” for the role. The producer of the play, Irene Selznick, had been thinking about John Garfield or Burt Lancaster for Stanley but Williams was enraptured. Brando did weights to get in trim.

“An impossible, psychopathic bastard,” Kazan remembered Jessica Tandy, who played Blanche DuBois on stage, commenting of her co-star. However, he was delighted with “the scorching power of this man-boy”, as he referred to Brando. He could understand the other actors’ frustrations (“Brando had mannerisms that would have annoyed the hell out of me if I had been playing with him”) but was astonished by Brando’s searing honesty. As he wrote, the actor’s “every word seemed not something memorised but the spontaneous expression of an intense inner experience”. That, of course, was the holy grail for method actors and Brando had achieved it right at the start of his career.

In spite of the play’s success, Warner Bros not only demanded a major star as Blanche in the film version of Streetcar (hence the casting of Vivien Leigh instead of Tandy). They also made it clear they would have “preferred someone not Brando”. Kazan demurred. He insisted on Brando.

“In Stanley sex goes under a disguise. Nothing is more erotic and arousing to him than ‘airs’ … she (Blanche) thinks she’s better than me … I’ll show her … sex equals domination,” Kazan’s jotted thoughts in his notebook for Streetcar (published in Michel Ciment’s book An American Odyssey) make the story seem like a New Orleans set version of Fifty Shades of Grey.

Predictably, in both the stage and subsequent screen versions of Streetcar, Brando’s charisma had a disarming effect on audiences. They “adored” Brando. Few seemed to realise that Tennessee Williams’s “primary sympathy was with Blanche”.

Kazan had initially been reluctant to make the film version. As he told Williams, “it would be like marrying the same woman twice. I don’t think I can get it up for Streetcar again.” In the end, he realised he could add new layers to the storytelling in a movie version. He could explore in yet more forensic detail Brando’s “exterior toughness” and his “tremendous desire for gentleness”.

“As fine if not finer than the play,” the New York Times enthused of the movie. “Brando carries over all the energy and the steel-spring characteristics that made him vivid on stage. But here, we’re so much closer to him, he seems that much more highly charged, his despairs seem that much more pathetic and his comic moments that much more slyly enjoyed.”

Viva Zapata!, scripted by John Steinbeck, is the least heralded of the three films Brando made with Kazan. It was a departure for the actor. This was an action movie, a western with a political slant in which he played a Mexican revolutionary leader. Again, the Hollywood studio heads had tried to pass him over. Fox boss Darryl Zanuck had wanted Tyrone Power for the role, reportedly complaining that he couldn’t understand Brando’s “mumbling”. To get in trim for Streetcar, Brando had pumped iron. To play Zapata, he needed to wear make-up, a moustache, a sombrero and to ride a horse. The familiar energy was still there. As Bosley Crowther wrote in his New York Times review, in the romantic scenes, the actor seemed “baffled and tongue-tied”, but when he was “at the head of his rebel-soldiers or walking bravely into the trap of his doom, there is power enough in his portrayal to cause the screen to throb”.

Whatever else, the role showed its director and star willing to take huge risks. Zapata was a very long way removed from Stanley in Streetcar or of the introspective anti-heroes Brando might have been expected to carry on playing.

The pivotal moment in Kazan’s life and career came in 1952, not long after Streetcar had lost out at the Oscars as Best Picture to An American in Paris in spite of picking up 12 nominations. The director took the fateful decision to name names of those he had known as communists during his own membership of the party in the 1930s to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). “Now came a storm of anger against me and among close friends, sick-hearted disappointment,” he later wrote of the indelible stain on his reputation. This was considered both as moral cowardice and as an act of rank betrayal. It was still being talked about when he won a Lifetime Achievement Oscar in 1999 and at the time of his death a few years later.

Brando couldn’t redeem Kazan’s reputation but his portrayal of the longshoreman in On The Waterfront gave audiences a sense of the director’s seething inner turmoil. Brando’s character Terry Molloy was based on Tony Mike, who had also “named names”, although in his case, the confession came to the Waterfront Crime Commission, not the HUAC.

The actor had been reluctant to take the part as Terry because he, like so many of their circle, disapproved of what “Gadge” as Kazan was nicknamed, had done. This, though, was Brando at his most transcendent.

“Brando, naked of soul in On The Waterfront, the best performance I’ve ever seen by a man in films because it had all the tenderness and delicacy in love scenes that you could not have expected,” Kazan wrote of his star in his autobiography. He called it “the perfect performance”.

If this was hyperbole on Kazan’s behalf, it was justifiable. Terry was the ex-boxer who “could have been a contender”. He kept pigeons. At the end of the film, he took one of cinema’s most horrendous beatings after his fight with union boss Johnny Friendly (Lee J Cobb). Brando played him as a blue-collar martyr, a hyper-sensitive bruiser. It was an astonishing portrayal.

Kazan may have cited Brando’s salary demands as the reason that he never worked with the actor again. A more likely expectation is that both men knew any further collaborations would have ended in anti-climax. Brando had already given him the “perfect performance” once and it would have been sheer hubris to have expected him to have done it again.

‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ opens at BFI Southbank and cinemas nationwide on 7 February. The BFI’s Elia Kazan season runs from 1 February to 17 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments