Lucky Logan's Steven Soderbergh: 'There are some directors whose names mean something to the general public. Mine’s not one of them'

The director quit movies, now he's back with 'Lucky Logan' - the first theatrical release he's directed in four years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Where would heist movies be without the Big Score – that payoff so irresistible it can lure the most jaded desperado out of hiding?

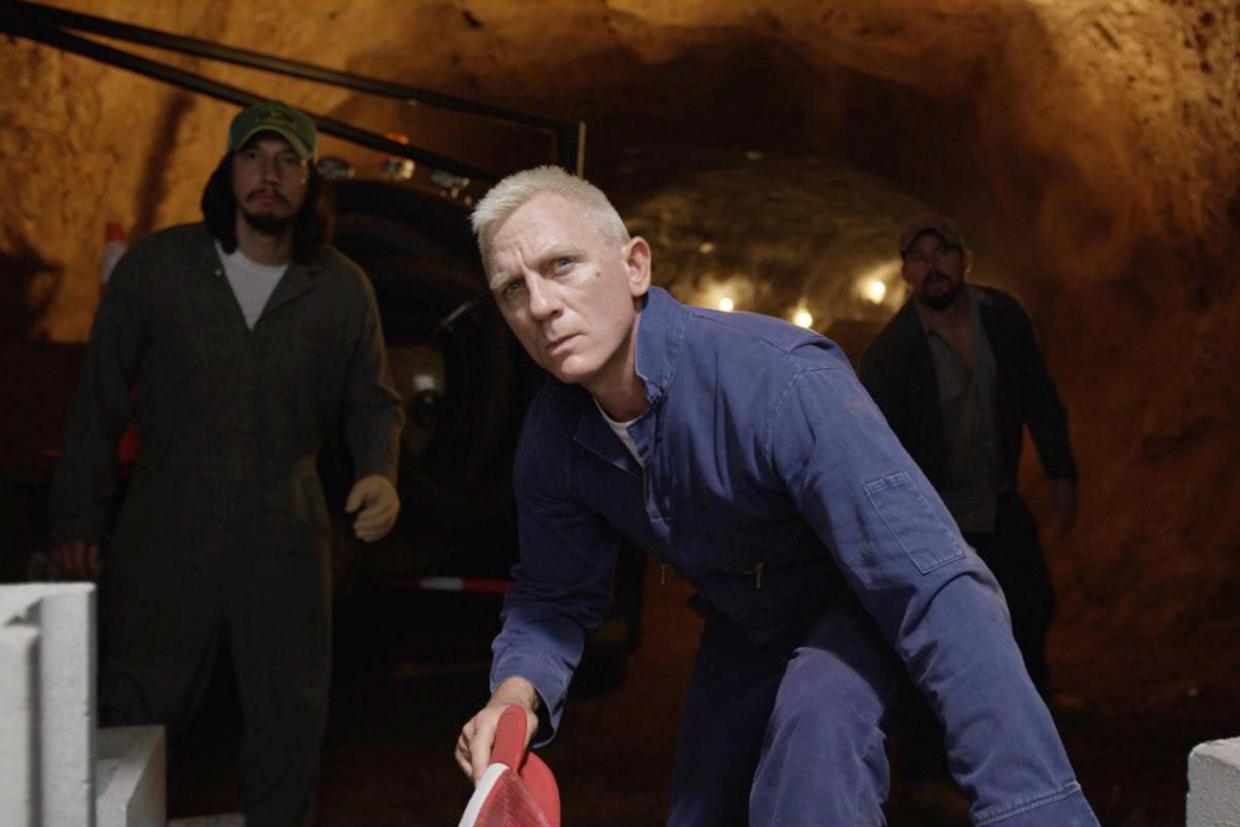

It’s the kind of temptation that propels many of Steven Soderbergh’s movies, and motivates him as a filmmaker, too. His latest feature, Logan Lucky, is once again about a group of larcenous but lovable characters: this time, a laid-off construction worker (Channing Tatum) who recruits his brother (Adam Driver) and sister (Riley Keough) as well as a volatile prison convict (Daniel Craig) to pull off the NASCAR racetrack robbery of a lifetime.

Logan Lucky, which opens on 25 August, puts a down-home spin on the elaborate capers in Soderbergh’s glitzier Ocean’s Eleven series. It is also the first theatrical release he has directed in four years, following what appeared to be several very unambiguous pronouncements that he was giving up filmmaking altogether.

Now that he seems to be going back on his word, Soderbergh is as gleeful as he is humbled. At various times in his career, he’s been an art house auteur, a must-have director of the moment, a renegade and a recluse. But he’s found what he wants to do is make movies that, whatever genre they fall into, can be seen by as many people as possible.

“I’ve been shooting my mouth off for a long time about aspects of the movie business I’m frustrated with,” he says. “I make declarative statements a lot that I then have to walk back. But I think the country’s used to that.”

It’s not that Soderbergh went into creative exile; he has continued to work on projects like The Knick, the ambitious Cinemax period drama that has been cancelled.

Logan Lucky is not his splashy re-emergence from any retirement, nor any statement on present-day America. It’s just the kind of story he likes to tell, perhaps because he sees the moviemaking process – when it’s executed correctly – as its own perfect crime.

As Soderbergh explains, “You’ve got a crazy idea. Odds are, it’s not going to work out, or at least not going to go the way you think. You put a team together, things go wrong, you come out the other end and hopefully you survive.”

Sitting in his TriBeCa office, the wiry Soderbergh, 54, is an inconspicuous man in an inconspicuous room. He wears horn-rimmed glasses and a T-shirt that read “A Mike Nichols Film”, and the small work space is decorated with knickknacks like a Peabody Award for The Knick and a sagging cat balloon (“Wishing You a Purr-fect Birthday”).

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

When he talks about his movies, in his enthusiastic, quietly intense way, it is a therapy where he makes on-the-fly realisations he missed during the filmmaking process.

“On set, people are intuiting what I’m doing by following me and seeing where I stop,” he explains. “Sometimes, until somebody asks me, I don’t even know how it works.”

And though he can be self-deprecating, Soderbergh, an Academy Award winner for his crisscrossing drug-trade narrative Traffic, is deadly serious when he says he is never going back to making the films he used to.

“I’ve really lost my interest as a director – not as a producer or viewer – in anything that smells important,” he says. “It just doesn’t appeal to me at all anymore. I left that in the jungle somewhere.”

After a career of independent breakthroughs (sex, lies and videotape), mainstream hits (Erin Brockovich) and occasional oddities (Full Frontal), Soderbergh said he was changed for the worse by Che, his biographical film about Che Guevara, which was released in two parts in 2008.

That film was a scramble to finance – European investors ended up footing its estimated $58m (£44.7m) budget – and a slog to shoot; Soderbergh spent about 10 weeks on it and still found himself wishing he’d had more time. Che ended up a critical success but a commercial dud, and it soured Soderbergh on prestige films. “’Che beat that out of me,” he said.

He spent a few years directing crowd-pleasers and genre movies like Contagion and Magic Mike. Then, amid some apocalyptic self-assessments – “In terms of my career, I can see the end of it,” he told The Guardian in 2009 – Soderbergh veered into stage plays like The Library and TV projects like The Knick and the Liberace biopic Behind the Candelabra.

Soderbergh said he was lured back to theatrical features in 2014, when he received the screenplay for Logan Lucky, credited to Rebecca Blunt. Though Soderbergh intended only to produce the film and find another director for it, he was drawn to what he felt was the script’s empathy for working-class characters who get to be more than caricatures.

“They surprise you with their thought process and their worldview,” he says. “The trick is to use stereotypes to set the table and then hopefully surprise people.”

Tatum, who worked with Soderbergh on Magic Mike and other movies, said the director had a talent for “the art of problem-solving,” but added that anyone in his position can be susceptible to “problem fatigue.”

“When you’re the director, everyone looks to you for everything,” Tatum said. “What colour is the pen going to be, Steven? What time do you want to wrap today, Steven? It’s all eyes on you, all the time.”

By taking a break from film, Tatum said, “he just wanted to change the radio station for a minute, off of something he was so used to – to shake things up.”

Logan Lucky allowed Soderbergh to retain complete creative control and sidestep the Hollywood studios: in a plan devised by Fingerprint Releasing (Soderbergh’s company) and Bleecker Street (an independent distributor), the movie will open in at least 2,500 theatres, Soderbergh said.

On the set last year, Driver said, Soderbergh worked quickly and decisively. “Nothing seems to really distract him,” Driver said. “He trusts his instincts and knows when he’s comfortable with moving on. It feels like kind of a protest, about how films are conventionally made.”

Even when Soderbergh doesn’t articulate his intentions, “he is actually speaking loud and clear, but he’s just not talking to anybody,” Driver said with a laugh. “You get the sense of, what does he need to say? He’s doing it.”

Soderbergh, who sometimes works pseudonymously as his own editor and director of photography, is a one-man band and also a trickster. The Hollywood Reporter has questioned whether Blunt, the Logan Lucky screenwriter, exists, and suggested that the film was in fact written by Soderbergh himself; or by TV host Jules Asner, his wife; or by comedian John Henson.

On Twitter, Soderbergh posted, “Rebecca Blunt is not a pseudonym for a male writer. She is a woman, and she wrote LOGAN LUCKY entirely by herself.” He told me simply that she was “highly amused” by this speculation and found it “very entertaining,” adding that Blunt – who has no other credits on her IMDb page – was busy with another writing assignment and unavailable for comment.

Asked about trade publication reports that said he was directing a new movie with Claire Foy and Juno Temple that he shot on an iPhone, Soderbergh offered a vehement if careful rebuttal.

“You could argue that it’s the perfect fake story, right?” he said. “It sounds plausible.” He acknowledged he had met with Foy and knows Temple through friends.

Soderbergh does not spend much time mourning projects that he feels lost their momentum, like The Knick, the critically acclaimed series that starred Clive Owen as a surgeon in early 20th-century New York. Soderbergh had directed 20 episodes over two previous seasons, and there were scripts prepared for a potential third season, written by its creators, Jack Amiel and Michael Begler. Even so, Cinemax cancelled The Knick in March.

Many factors played into this decision, Soderbergh said, including the overall cost of the show – “when you get up into the $6 million an hour range, that’s not cheap,” he said – and Cinemax’s decision to focus on action-oriented programming.

Ultimately, he did not lay the blame for the show’s cancellation at anyone’s feet. “External forces were at play that had nothing to do with the show itself,” he said.

Keough, who also appeared in Magic Mike and starred in a TV adaptation of Soderbergh’s film The Girlfriend Experience, said he is “always trying to do things that are a little bit risky.”

She added, “I could imagine that would be really stressful. But he definitely doesn’t show me that side of him.”

Nearly every other director she has worked with, she said, has asked her what it is like to work with Soderbergh. “I get asked about Steven Soderbergh more than I get asked about my grandfather, honestly,” said Keough, who is a granddaughter of Elvis Presley.

Soderbergh does not see himself this way, and hardly expects that promoting Logan Lucky as his return to cinemas will compel anyone to see it.

Pointing to filmmakers like Christopher Nolan and Martin Scorsese, he says, “There are some directors whose names mean something to the general public. Mine’s not one of them.”

In the films and TV shows he collaborates on now – whether Mosaic, an interactive movie he has directed for HBO, or Ocean’s Eight, an all-star female-led heist movie starring Sandra Bullock and Rihanna that he is producing for the director Gary Ross – Soderbergh said his only goal was to tell stories that are accessible, not esoteric.

“It’s really easy to make a movie that five people understand,” he said. “It’s really hard to make something that a lot of people understand, and yet is not obvious, still has subtlety and ambiguity, and leaves you with something to do as a viewer.”

Among the contemporaries whose work excited him, he singled out M Night Shyamalan, the oft-derided suspense director. He has reinvigorated himself with recent movies like The Visit and Split, Soderbergh says, adding, “He went back to his roots and has rebuilt himself, and is right back where he was.”

Given the choice, Soderbergh has no interest in being a personality and would much rather let his work speak for himself. Anonymity, he said, suits him just fine.

Looking ahead to next year’s release of Ocean’s Eight, he says, “I can’t wait for Rihanna to see the movie and it says ‘Produced by Steven Soderbergh,’ and she’s like, ‘Who the hell is that?’ Because I’ve never met her. I’ve seen her, but I’ve never met the woman.”

‘Lucky Logan’ is on general release on 25 August

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments