The world of Korean noir: Extreme violence, dwelt on with relish, seems to be de rigueur

With the 12th London Korean Film Festival in full swing, we take a look its strand of film noir which has established characteristics of its own within the international noir world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Film noir is an elusive and protean genre – so much so, some might question whether it can even be considered a genre. Should it rather be defined as a style, a mode, a cycle, a state of mind? Does “film noir” just refer to those black-and-white American films produced during the classic period 1940 to 1958? For the purists, Korean noir might be dismissed as a contradiction in terms. But these days, most critics would probably agree that authentically noir films, and films drawing on noir-esque elements, can be made anywhere and at any time.

Even during the heyday of Hollywood noir, other countries were dabbling in the same shadowy pool. In Britain, Carol Reed directed Odd Man Out (1947) and The Third Man (1949), both sharing a key noir theme: the man on the run. As does another British film boasting what must surely qualify as the archetypal noir title, Night and the City (1950), directed by the American-born expat Jules Dassin. Dassin moved on to Paris, where he directed another noir classic, Rififi (1955) – an French heist movie that explores a further common theme of noir, that of loyalty and betrayal.

Another leading practitioner of Gallic noir was Jean-Pierre Melville, whose crime movies – Bob le flambeur (1956), Le Doulos (1963), Le Samuraï (1967) – brought a dark stylised poise to the mythology of the gangster film. In Japan, elements of noir were creeping into the modern-day films of Akira Kurosawa: The Bad Sleep Well (1960) and High and Low (1963).

How to define noir? Screenwriter and director Paul Schrader is often quoted as saying: “It is not defined ... by conventions of setting and conflict, but rather by the most subtle qualities of tone and mood.”

“Most subtle” might be questioned; even in its Hollywood heyday, noir could easily spill over into excess. And in 21st century Korean noir restraint barely figures. Extreme violence, dwelt on with relish, seems to be de rigueur. Prolonged scenes of torture are frequent. Extensive combat sequences involving multiple assailants wielding assorted weapons, accompanied by copious bloodshed, are extended beyond all plausibility. Blatant and endemic corruption is almost a given element.

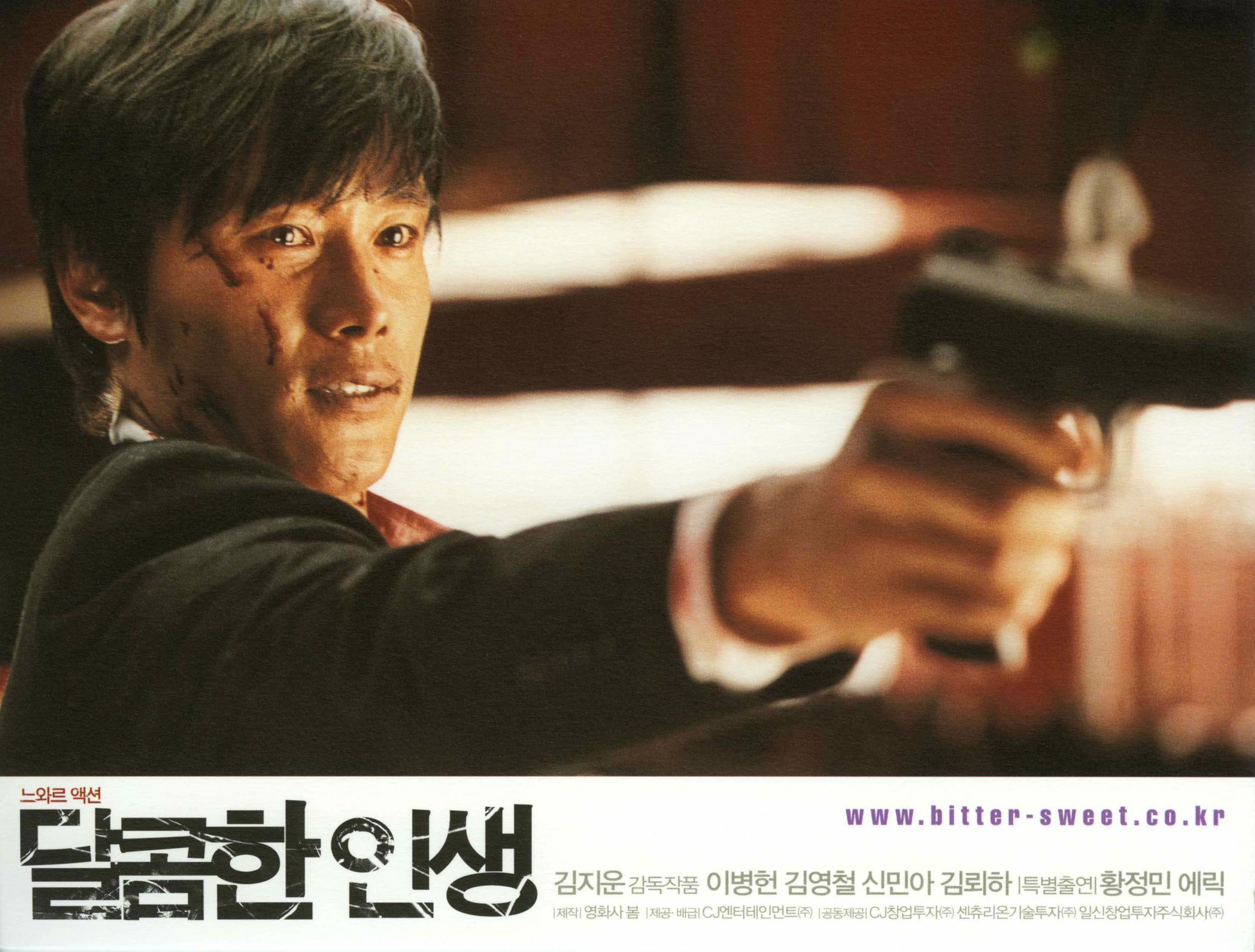

Often, Korean noirs pivot on matters of loyalty and betrayal. A protagonist may be a member of a criminal hierarchy who fails to exhibit total loyalty to the boss. Sun-woo, protagonist of Kim Jee-woon’s A Bittersweet Life, offers a case in point. Hotel manager and enforcer for the hotel’s crime-lord owner, he allows one brief humane impulse to divert him from orders. Retribution follows at once: he’s humiliated, beaten up, tortured and finally buried alive.

A similar plot with an all-female slant fuels Han Jun-hee’s Coin Locker Girl (2015), whose heroine is a street orphan raised by her adoptive mother, a Fagin-like Incheon gang boss, to do her dirty work. Like Sun-woo, she succumbs to a moment of pity for one of her designated victims, which runs her into serious trouble with “Mom”.

A variant of this plot-structure underlies Kim Sung-soo’s Asura: The City of Madness. Han Do-kyung is a rogue cop in the pay of the corrupt Mayor Park. But when he kills a fellow officer he comes to the attention of a chief prosecutor who’s out to get the mayor and demands Han’s help. Han’s loyalties are now pulled two ways – and things can only end badly.

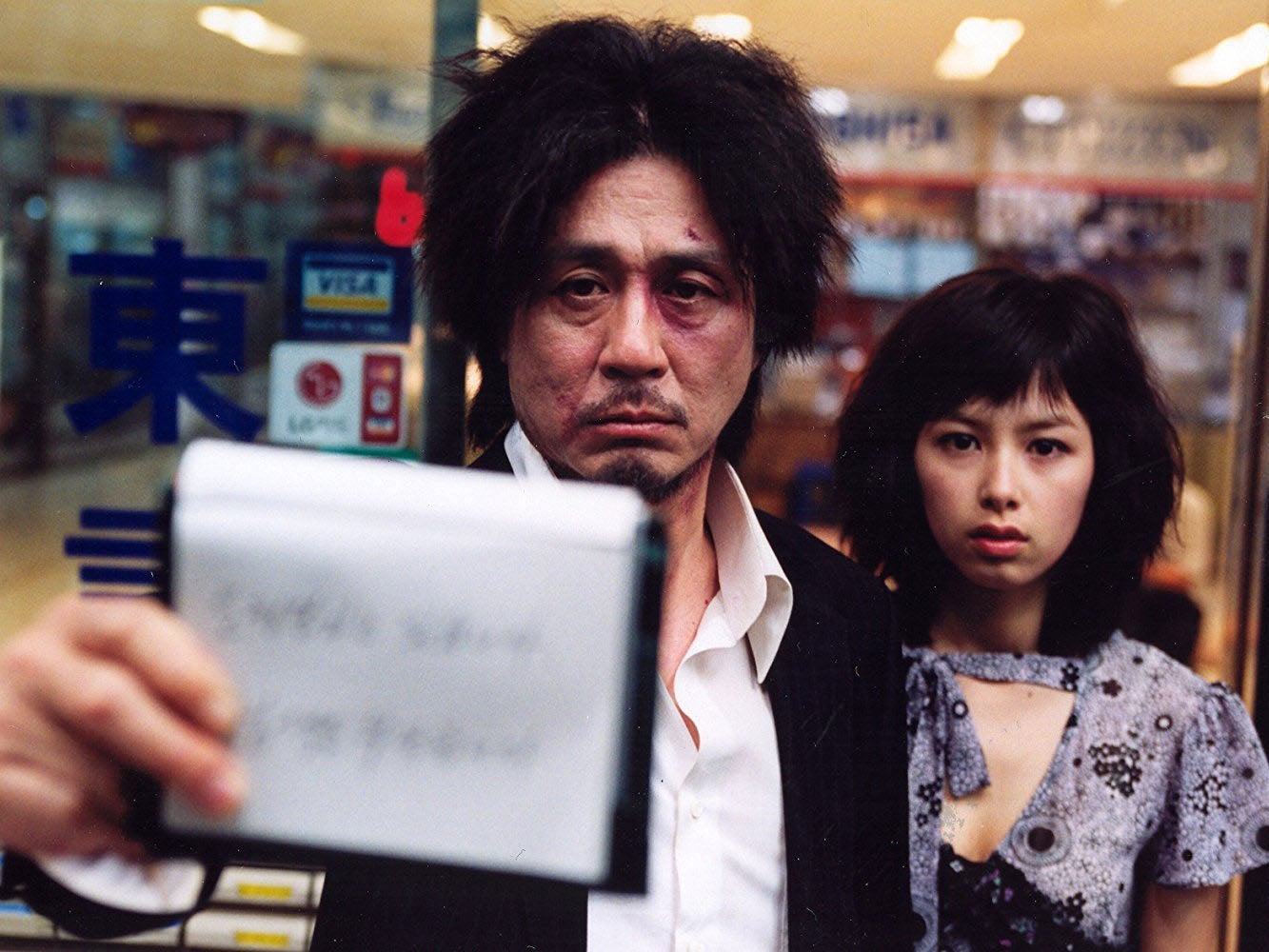

A still more frequent theme in Korean noirs is that of revenge – as in Park Chan-wook’s Vengeance Trilogy – Sympathy for Mr Vengeance (2002), Oldboy (2003) and Lady Vengeance (2005). Oldboy is perhaps the most widely known example of Korean noir to date. The protagonist, Oh Dae-su, wakes from a drunken night on the town to find himself imprisoned for no apparent reason. He stays locked up for the next 15 years before being equally mysteriously released and told he has five days to work out why he was incarcerated.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Vengeance is Oldboy’s key theme, but we’re some way into the film before we learn just who’s avenging themselves and why. It also suggests that vengeance often backfires on the avenger. This equally applies to Sympathy for Mr Vengeance where a child-kidnapping goes disastrously wrong, resulting in unpleasant deaths for the child, the kidnappers and eventually the child’s revenge-seeking father. The heroine of Lady Vengeance does finally survive, but only at the cost of considerable physical and psychological damage.

Many protagonists in Korean noir are positioned as social outsiders. A maverick cop is the hero of Ryoo Seung-wan’s The Unjust (2010), called in to solve the case of a serial killer who targets schoolgirls. In Na Hong-jin’s The Chaser (2008), Eom Jung-ho is even more of an outsider – an ex-cop turned pimp. Still, he’s the only one to nail a sadistic killer of prostitutes, while the regular cops are depicted as bumbling incompetents.

The protagonist of Na’s follow-up film, The Yellow Sea (2010) is yet another outsider – a cab-driver from the Chinese province of Yanbian, where many ethnic Koreans live. Hopelessly in debt thanks to his gambling addiction (mahjong rather than poker or roulette), Gu-nam ill-advisedly accepts a substantial sum from a local gang boss to come to Seoul and murder a man he’s never met.

As I’ve aimed to show through these few examples, Korean noir has in recent years established characteristics and conventions of its own within the international noir (or neo-noir) world. The screening of Jung Byung-gil’s The Villainess (2017) as a teaser to this year’s London Korean Film Festival, and of Byun Sung-hyun’s The Merciless (2017) in addition to several more noir titles in the festival proper, shows that the cycle is far from exhausted.

Philip Kemp is a film critic and historian. The 12th London Korean Film Festival runs until 19 November in London and the UK (www.koreanfilm.co.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments