London Film Festival 2017: From Ghost Stories to The Killing of a Sacred Deer, why horror is having its moment

As It dominates the box office, genre films are being more recognised and celebrated on the festival circuit

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After a terrible summer of box-office woes, there’s been one movie that’s almost singlehandedly saved the day: Andy Muschietti’s adaptation of Stephen King’s It. Somehow, the supernatural horror has tapped into the zeitgeist, bringing traditionally non-horror viewers to the cinema. Earlier in the year, Get Out managed the same, impressing critics and audiences alike while grossing $252.4m (£193.4m) from a $4.5m budget.

Come festival season, it’s clear that horror/genre movies have finally found their place on the circuit. Notably, the London Film Festival (LFF) – traditionally known for featuring niche world cinema – has accepted these scary/terrifying flicks with open arms, horror making up a large percentage of the most talked-about films.

Heading up the pack comes The Shape of Water, a fantasy romance from horror auteur Guillermo del Toro that heavily borrows from the genre. Then there’s Brawl in Cell Block 99, directed by Bone Tomahawk’s S Craig Zahler and featuring some of the most violent scenes depicted on screen in recent years. The Killing of a Sacred Deer, from The Lobster’s Yorgos Lanthimos has been terrifying festival-goers since Cannes. Joachim Trier’s supernatural thriller Thelma (about a girl whose sexual awakening triggers some fantastical powers) will also be screening, as will the upcoming Jeffrey Dahmer biography My Friend Dahmer.

“It’s a really great year for horror and genre in general,” says Michael Blyth, curator of the Cult strand, a banner under which many of these films are playing. Thanks to the Cult strand – which has been running for six years – more and more genre, horror, and fantasy fiction movies have found their way onto the line-up.

“For a long time, there was was something missing from LFF, an audience we weren’t serving. We started the Cult strand because it seemed only time we showcased horror and science fiction. Before then, we’d show one or two every year. Now, with a specific focus on this type of cinema, we are taking horror seriously and exhibiting genre in more ways.”

Blyth uses The Shape of Water – an Oscar frontrunner – as an example of how times have changed. “Del Toro is obviously a huge horror fan, all his work is somehow indebted to the genre. This is very much a love letter to those movies. He’s done it in a way that’s beautiful, engaging and romantic. As a result, the movie appeals to the hardcore horror crowd but has a life beyond that.”

One term that’s been thrown around recently is “elevated horror”, especially since the successes of Get Out, It Follows and The Witch. The term, though, implies there’s a limit to how good normal horror movies are before they become something different.

“What users of the term are saying is there’s an unacceptable type of horror and acceptable,” Blyth says. “When these films are critically acclaimed, winning awards, we shouldn’t shy away from them being horror. When I’m programming for the festival, I’m celebrating them as horror movies. I’m saying, ‘if you like horror movies, come and see them, because they’re going to be completely satisfying’. it’s very important we talk about horror in the purest forms.”

Although the genre has been notably successful recently, horror has nearly always had a place in mainstream cinema. Throughout the Eighties, slashers were particularly popular. Come the Nineties, a wave of post-modern horrors swept across cinema, followed closely by torture porn. One reason, as mentioned above, is their ability to tap into the populous zeitgeist.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“Over the years, horror has consistently – in literature and film – pushed the envelope on things we need to look at and talk about,” says Andy Nyman, the co-director of Ghost Stories, a “supernatural thriller/horror” playing at LFF. “One of the reasons It seems so resonant at the moment is the film’s message, that fear itself is something you should be scared of. It’s doing that in a world where we’re constantly told to be afraid of shit that we don’t need to be afraid of.”

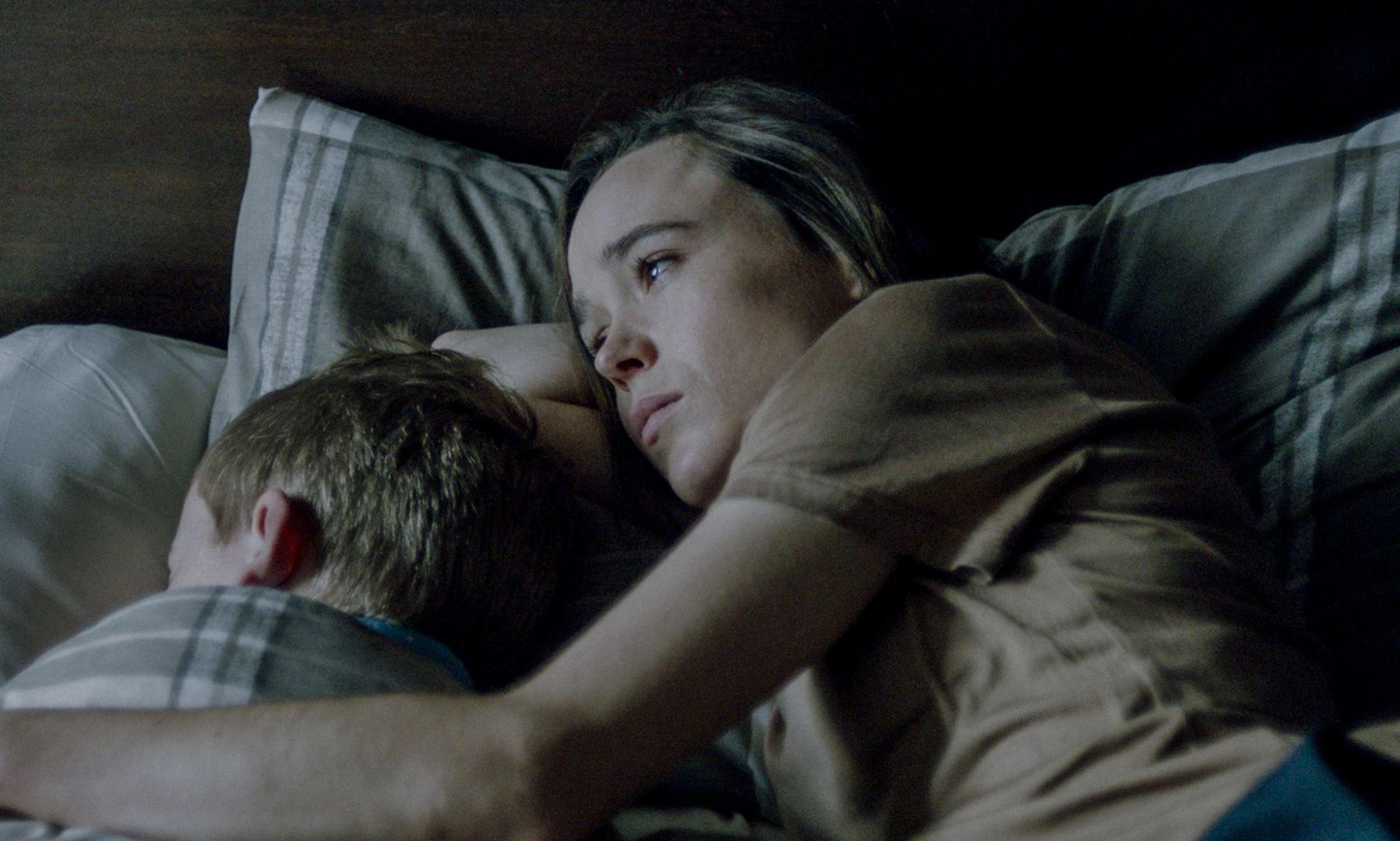

Nyman points to one of the most iconic horror movies ever made – George A Romero’s Dawn of the Dead – noting how the auteur was showing the world how consumerism was literally turning people into the walking dead. Similarly, debut director David Freyne uses zombies to represent a political point in The Cured, starring Ellen Page and also showing at LFF.

Unlike Dawn of the Dead, the new thriller looks at zombies who have been cured, now acting as regular human beings. Of course, there’s a catch: they can still remember all the atrocious deeds they committed as brainless, undead walkers. Plus, the rest of society holds these “cured” people accountable for those heinous acts, shunting them down in society. One of the main characters, played by a terrifying Tom Vaughan-Lawlor, was a lawyer but – once returned to normal life – has been forced to become a cleaner.

“I started writing it six years ago after seeing these populist politicians in Europe not thinking it would last,” says the Irish director. “I didn’t think Farage or Le Pen would last, but they’re a symptom of the discontent from back then. In a horribly fortunate way, it’s kept its relevance.”

The script was eyecatching enough to gather the attention of Page, who came aboard after seeing some of Freyne’s short films. One of them, The Mill, had previously screened at LFF, but having The Cured play this year “is a dream come true”. Notably, those shorts have nearly all been horror.

“I’ve always been passionate about the genre,” Freyne says. “There’s so much talk about the death of the theatrical experience but there are few genres that work as a communal experience like horror. Being in a room – hearing those gasps, those awkward laughs after being frightened – it’s really lovely. They do benefit from being in a dark room with lots of people.”

Nyman agrees with the sentiment. “Like comedy, horror is a shared experience that people love,” he says. “Sitting in a room with hundreds of people where everyone jumps or gasps at the same time, that’s a phenomenal experience. A drama is a much more isolating experience.”

Of course, Nyman’s film Ghost Stories started life as a play, one that has terrified over half a million people around the world since premiering at the Liverpool Playhouse back in 2010. “We wanted give people an experience,” he adds, keeping the plot a mystery, hoping to preserve the thrill for the cinema. “The film, though, is not a traditional horror. Like all good stories, it takes the audience on a journey – quite an odd journey, that doesn’t really make sense until the very end.”

That’s not to say Nyman’s not a fan of traditional horror. One of the ways he bonded with co-director Jeremy Dyson (best known for The League of Gentlemen) was over a shared obsession of horror, particularly the work of Dario Argento, Mario Bava and Tobe Hooper.

“I’ve been that way inclined for as long as I can remember,” says Dyson. “Growing up in the Sixties and Seventies was a great time. There was great stuff on television, stuff that’s now looked upon as classic. So many of my colleagues were formed by that classic era of Doctor Who. And, when you go back and look at these things, they’re still terrific, with so many big ideas flying around. No wonder it was a crucible for an entire generation of writers.”

One thing that’s particularly interesting to Nyman is how neither horror nor broad comedies have the critical or award respect that other films often get. Despite being mainstream, there’s traditionally been a certain amount of snobbery regarding horror, something Dyson elaborates on.

“These stories are ancient, they’re from mythology,” he says. “The enlightened minds look down upon them as remnants of a superstitious time, the same way they do with religion. Horror’s also visceral, the same way broad comedy is visceral, in that it bypasses the intellect and mutes the critic. For comedy, if it makes an audience laugh, what more can you say? For horror, it’s the same as making a room of people scream.”

Thankfully, things are changing. Alongside LFF showing more genre films, the BFI has run numerous horror events, recently hosting a festival dedicated to the many adaptations of Stephen King’s works. Dyson points out that critics such as The Observer’s Mark Kermode – an out-and-out horror fan – have also moved the conversation forward, helping erode the snobbery often associated with reviewers.

“The success of the new It is very exciting,” says Blyth. “Hopefully, It will be a huge turning point. That’s a film that people aren’t discussing in this elevated way. They’re talking about it as just a good old-fashioned scary horror movie. Hopefully, people will just begin making unashamedly horror movies. Fingers crossed, we can see another horror renaissance.”

Considering how many of these horrors have been well received over the last year on the festival circuit, horror’s moment in the spotlight certainly looks set to continue.

Ghost Stories, The Cured, Brawl in Cell Block 99, My Friend Dahmer, Thelma, Killing of a Sacred Deer and The Shape of Water are all showing at the London Film Festival. Buy tickets on the BFI website.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments