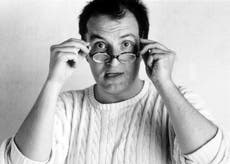

Kit Hesketh-Harvey, the last of the Vaudevillians, was that genuine rarity: funny both on stage and off

The screenwriter, musician, composer, actor and performer has died suddenly aged 65. David Lister pays tribute to a man who always revelled in that quintessentially English humour

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Kit Hesketh-Harvey was one of those surprisingly rare performers whose personality was the same on stage as off. When I saw him in the many revues he would write and perform, the audience basked in his humour and genuine warmth.

You could say that Hesketh-Harvey was the last of the old-style Vaudevillians, keeping alive the spirit of Noël Coward, while unafraid to surprise his audience by stepping into the caustic territory of Barry Humphries. He always revelled in that quintessentially English humour, self-deprecating but biting, drawing on a world of shared references from British culture, while at the same time carving out its own originality.

His version of Gilbert and Sullivan’s “A Policeman’s Lot Is Not a Happy One” turned the jolly jape of a song into a critique of modern-day policing. “They want evidence that can’t be circumvented. So, invent it.” Delivered with such a smile, it could take a few seconds for the social comment in his lyrics to strike home.

Sadly, those who search online for examples of him in performance will find there is far too little preserved. The memories of his friends and his audiences may have to serve. But even the little that exists gives an indication of his originality.

I still can’t help but chuckle at the rendition of Abba’s “Fernando”, rewritten in honour of a well-known chicken restaurant. To Abba’s tune he would begin: “It’s extremely cheap at Nando’s, they’ve got an uber-friendly waiting staff to put you at your ease”, leading to the chorus: “There was something in the food that night that wasn’t right at Nando’s.”

Of course, he would extemporise, involving the audience by fixing some unfortunate woman with a stare and saying: “Look at the colour of that jumper, that’s pure Brora, she’s never been to Nando’s in her life.”

Hesketh-Harvey was much more than a performer with a stage presence that was infectious in its bonhomie. He can boast of launching Hugh Grant’s career, with his script for the film Maurice, an adaptation of the EM Forster novel, perhaps the most sensitive and thought-provoking of all the Merchant-Ivory films. And he was something of an unsung hero in his work on the scripts of The Vicar of Dibley.

One could go on. Hesketh-Harvey was nothing if not eclectic. After scripting Maurice in 1987, he won the Vivian Ellis award for musical theatre writers the following year and went on to study under Sondheim. He starred in revues such as Cowardy Custard, a tribute to Noel Coward, and Tomfoolery, which celebrated the satire of Tom Lehrer. Probably, though, most people who saw him on stage will have seen him as one half of Kit and the Widow, his musical-comedy cabaret act with pianist Richard Sisson, a fellow member of the Cambridge Footlights, and later James McConnel. But he also translated and helped develop productions for leading opera companies. He wrote crime novels. And, only 18 months ago, he wrote the libretto for Grange Park Opera’s The Life and Death of Alexander Litvinenko. Shortly after doing that he did his annual stint in panto, this time playing King Rat in Dick Whittington. He devised musicals and leavened all this with appearances on BBC Radio’s Just a Minute and Quote Unquote. He even managed to collaborate with Giffords Circus. Oh, and he was an agony uncle for Country Life magazine. The term polymath didn’t really begin to do him justice. Even Renaissance Man feels like selling him short.

And, as if to prove that he was forever redefining the word eclecticism, he had recently been working on a project called Pilgrims, and had composed with Roderick Williams a religious anthem, due to be performed at Magdalen College, Cambridge. Interest in religion ran through the Hesketh-Harvey family. After the break-up of his marriage to former Bond girl Katie Rabett, he set up home in the vestry of a 14th-century Norfolk village church. His sister, the former Evening Standard editor Sarah Sands, wrote a book on monasteries. With her first husband missing during a hiking trip, this is a tumultuously distressing time for the family.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

The interest in choral music was very much a part of Hesketh-Harvey’s formative years too. Born in Nyasaland, now Malawi, where his father was district commissioner, he was educated as a senior chorister at Canterbury Cathedral and subsequently gained a choral scholarship to Clare College Cambridge, where, in a foretaste of things to come, he mingled the study of serious music with comedy, joining the Cambridge Footlights.

Friends recall a dashingly good-looking young man at Cambridge and joke about the contrast between his persona then and the bald “mad monk” figure living in a vestry in recent years, as he perhaps developed a more introspective and questioning view of life that is so often the comic’s lot.

But for all the undoubted sadness, those same friends will find it hard not to think of him with a smile. In private, he could be the life and soul; again, that genuine rarity of a comedian on stage who was just as funny and endearing when he wasn’t performing. He really was a modern-day Noël Coward, flamboyant on stage and off. His friend Fiona Carnarvon, chatelaine of Highclere Castle, the setting of Downton Abbey, recalls him always coming down to breakfast in a variety of silk dressing-gowns. He might then enliven a meal by reciting his “Ode to a Haggis”.

As with Coward, one could expect a memorably crafted witticism in what appeared to be off the cuff, occasional remarks. “Poppers?” he once opined, “Harmless but for a slight headache or nausea: like ice cream, Viagra and the Kardashians.”

And Hesketh-Harvey was not shy of making gentle fun of one of his most acclaimed mentors, the often melody-free Stephen Sondheim. Performing at the first ever Comedy Prom, he sang: “People who like Sondheim always keep their buttocks clenched.”

Not a bad opening line of a song. He was unsparing to the big names of his profession. In one show he wanted to pay tribute to Andrew Lloyd Webber, who had a musical on in the theatre next door, but told his audience: “We wanted to do the big tune from Sunset Boulevard,” then sotto voce, “but between ourselves we couldn’t find a big tune.”

Kit Hesketh-Harvey traded in a disappearing brand – polite campery, inoffensive but often ingenious humour

His passion for theatre was huge and extended to his yearly Guildford panto stint. After he played King Rat in Dick Whittington, he told the former culture minister Ed Vaizey in a podcast, “Pantomime is tremendously important. It’s the child’s first experience of the theatre, generally. And it’s the first time you can grab a child by the metaphorical collar and say, ‘Look, this isn’t a video game. This isn’t a film. This isn’t telly. This is something much more exciting called theatre.’ And the villain always comes on first, of course. Downstage left is actually reeking with tradition, and you get a minute in which to terrify the kids.

“But King Rat is one of the best because he’s got this tail, you see. He’s got this tail which is very good for what panto has to do, which is play on two levels. One for the children, enthral them and terrify them and make them laugh and clap and sing. And then at the same time, nodding and winking to the grown up saying, ‘Isn’t this all ridiculous? Isn’t it fun? Isn’t panto stupid?’”

But, generally, in a world of in-your-face comedy and ever more risqué jokes and situations, Hesketh-Harvey traded in a disappearing brand – polite campery, inoffensive but often ingenious humour, with the sparkling wit often covering a layer of social comment. And just like his hero Noel Coward, he excelled in clever wordplay, wit and satire which may have taken few prisoners, but did so with exquisite tastefulness. One critic said his was “the acceptable face of camp, musical comedy”.

His was the gentle life-affirming humour of a man who himself seemed a gentle, life-affirming soul. If it seemed to belong to another age, then it was an age we should try to cling on to.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments