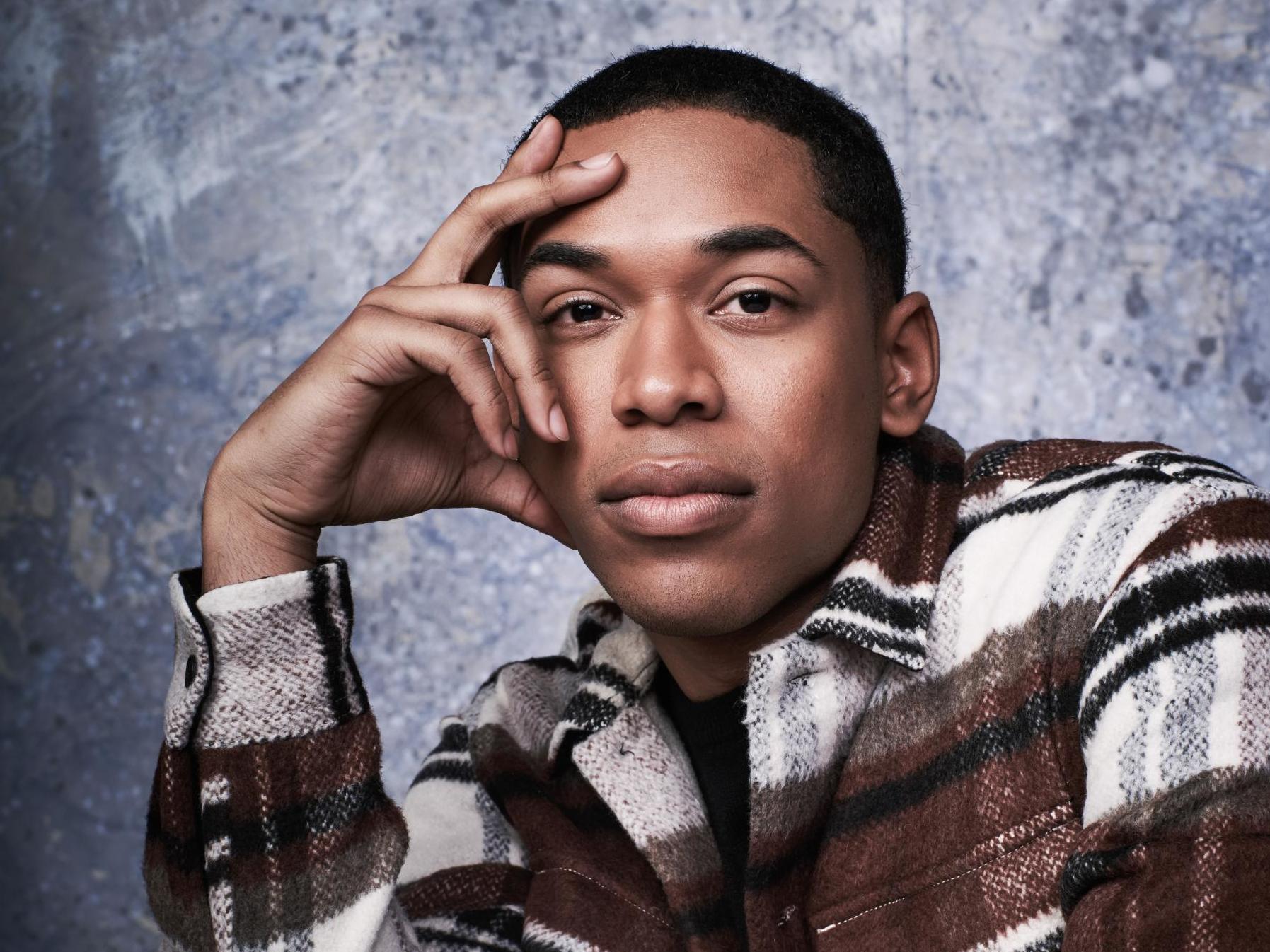

Kelvin Harrison Jr: ‘As a black man in America you can be in the wrong place at the wrong time and be shot to death’

The ‘Waves’ star talks to Ellie Harrison about the pressures of black excellence, his new film ‘The Photograph’, and why Donald Trump wouldn’t be a fan of his movies

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When I went to high school, I was trying to become something I wasn’t,” says Kelvin Harrison Jr. “I started to become very shameful of who I was, where I came from and the colour of my skin.”

The 25-year-old star of Waves cut his teeth with small parts in 12 Years a Slave, Roots and The Birth of a Nation, and used to joke that he’d set a world record for starring in the most movies and TV shows about slavery. But he hasn’t always been so in touch with the history of black America. In fact, he had tried to forget it.

Harrison was one of a handful of black students at his private school in New Orleans, where he had a scholarship and felt a desperate need to fit in with his white peers. “Those projects [about slavery] were a chance for me to take a deeper dive,” he says, “because I was dismissing my history as an African American. I was assimilating to the culture that was set at my high school that wasn’t mine. There was a very naive, immature part of me that just felt, ‘I want to move forward. We have so much opportunity now. Why do we have to dwell on the negatives?’

“But now, when I do these movies about young black people, I always want to make sure there is this underlying root of the strengths from my ancestors, and that their history is present in the experience. It empowers us as young people of colour.”

Being in such a small minority at school had a profound impact on Harrison, one that has bled into his roles. Luce, the character he plays in the 2019 psychological thriller of the same name, is a former child soldier from Eritrea. After being adopted by a white family in Virginia, he is put through years of intensive therapy, and gradually moulded and polished into a star athlete and model student.

“It was so cool to apply all the things I acquired in my own life to the part, like code-switching,” says Harrison. “It’s switching from the euphemisms of black culture and talking to black people, to suddenly walking into white spaces and making white people feel safe.”

Even though Luce is far from perfect, using his charm and intellect to manipulate those around him, Harrison found the role empowering. “Often I play characters without any agency,” he says, “but Luce wasn’t interested in taking no for answer or people telling him who he was going to be. That’s important for young people right now. To stop being so afraid and shrinking themselves and thinking they’re less than what they are actually worth.”

Harrison grew up in the leafy Gardens District of New Orleans, his father a jazz saxophonist and his mother a dancer and jazz vocalist. “Music was such a huge part of our home,” he says. His extended family would gather at his house, jamming and singing together “like on a talent show”. He also played piano in church and his little sisters learned the flute. “My family was like our own version of Jackson 5,” he says.

Before he started acting, Harrison was on the path to becoming a jazz prodigy. The amount of trumpet and piano training he did as a child, he says, was “ridiculous”: hours of practice every evening after school, performing in church every Sunday and three jazz camps every summer for years.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

But it wasn’t his passion. “I didn’t find my true voice in it at all,” he says. “I felt like I was intellectualising it too much, but art isn’t supposed to be so heady.”

When he was 12, Harrison snuck into a drama lesson at school to give an impromptu comedic monologue about having his fly unzipped in front of the class. So began his acting career. He kept his aspirations “on the down-low” for years afterwards, and instead of confiding in his parents, he would turn to Google for questions like, “How do you get on the Disney channel?”

The reason for Harrison’s secrecy was to avoid letting down his father, who wanted his son to experience the musical success he never quite achieved. Their relationship heavily inspired Harrison’s breakout role. In Waves, for which he helped director Trey Edward Shults develop the script, he played a high school senior under immense pressure to secure a wrestling scholarship at college. The film is like a panic attack followed by a hug. First, Tyler’s life spirals out of control as he masks a severe shoulder injury with addictive painkillers. Then, in the aftermath of unexpected calamity, the film’s narrative abruptly shifts to his younger sister and her tentative teenage love story.

“With my dad, it wasn’t wrestling,” says Harrison. “For him it was the music, and the pressure on me to keep doing it and practice non-stop. It was the lack of empathy and patience with a young person, and the idea that tough love is the only version of masculine love that’s presentable. All my dad wanted to do was set me up to be aware of the fact that there are injustices and inequality. As a black man in America, you can step outside and be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and be shot to death.”

When I ask if he is alluding to police brutality against the black community, his reply is emphatic. “Exactly.”

In one profoundly moving scene in Waves, Tyler’s father – portrayed with crackling intensity by Sterling K Brown – tells him, “We are not afforded the luxury of being average.” This was closely based on a conversation Harrison had with his own father. One day, he came into his son’s bedroom and said, “You have to work 10 times harder than the white person next to you. Your opportunities won’t be the same as his. That’s just how the world works.”

Harrison says his dad wanted him to “be the best” or not bother at all. “That’s scary when you’re 16 and not sure what you want to do,” he says. “I was like, ‘It’s hard for me to buckle down. You did jazz because you loved it. I’m doing it because I love you.’”

After his father saw Waves, Harrison says, “it made us want to talk about our own traumas. He’s so much more aware and sensitive of my feelings towards things now. He has an open heart and an open ear more than ever before in our relationship.”

At one point, Harrison’s manager asked him if he wanted to quit Waves. They weren’t sure the pivotal scene, where Tyler commits a horrendous act of violence in a moment of despair, could be pulled off. “Everyone was very nervous,” says Harrison. “It was one of those things, like, how are we going to handle this? Is this what we want to see from a young black man in 2019? We needed to make sure that arc felt justified and full.”

Harrison helped Shults, who is white, to ensure the film felt authentic to the African American experience. “We went through every beat,” he says, “and I’d be like, ‘Maybe this wouldn’t happen’ or ‘This is too far’ or ‘I understand your dynamic here, but in the black community, this would actually shift this way.’”

For his new film, The Photograph, no such guidance was needed. The glossy romance was written and directed by Stella Meghie, one of the most prolific black female filmmakers today. It follows a woman (Issa Rae) mourning the death of her famous artist mother, and the journalist (Lakeith Stanfield) who falls in love with her. Harrison plays an upbeat but frustrated intern at his newspaper. “When I read the script,” he says, “I remember laughing and thinking, ‘Oh my god, yes, I know that. I hear the language, the way we flirt, the understanding of hair and experience and struggle and pain and love.’ I totally identified.”

He wishes there had been more representations of black love on screen when he was younger. “The best I ever got was watching [US sitcom] That’s So Raven and seeing Raven’s parents be a happily married couple,” he says. “That was the extent of that. For me, it was like, I love The Notebook and Love Actually, but what about my experiences?”

Harrison’s next project is Aaron Sorkin’s long-in-the-making The Trial of the Chicago 7, also starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt and Eddie Redmayne. The film is based on the infamous 1969 trial of seven defendants who were charged by the federal government with conspiracy, inciting to riot, and other charges related to anti-Vietnam War and countercultural protests.

It’s a political film, helmed by a director who famously detests Donald Trump. What does Harrison think the president would make of his cinematic career to date, given his nostalgia for Gone With the Wind, a film that glorified slavery? “I don’t know what that dude would think,” he says. “Trump’s mentality comes from a place of fear and insecurity. He tries to control people in spaces where they aren’t allowing themselves to be dictated to. That’s sometimes scary, when you yourself feel very small and so very impotent in your own life.”

Harrison laughs at the thought of Trump watching Waves in the White House. “I don’t think he would like my movies, but that’s OK,” he says. “He would be challenged if he saw them, and that’s all that matters.”

The Photograph is in cinemas now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments