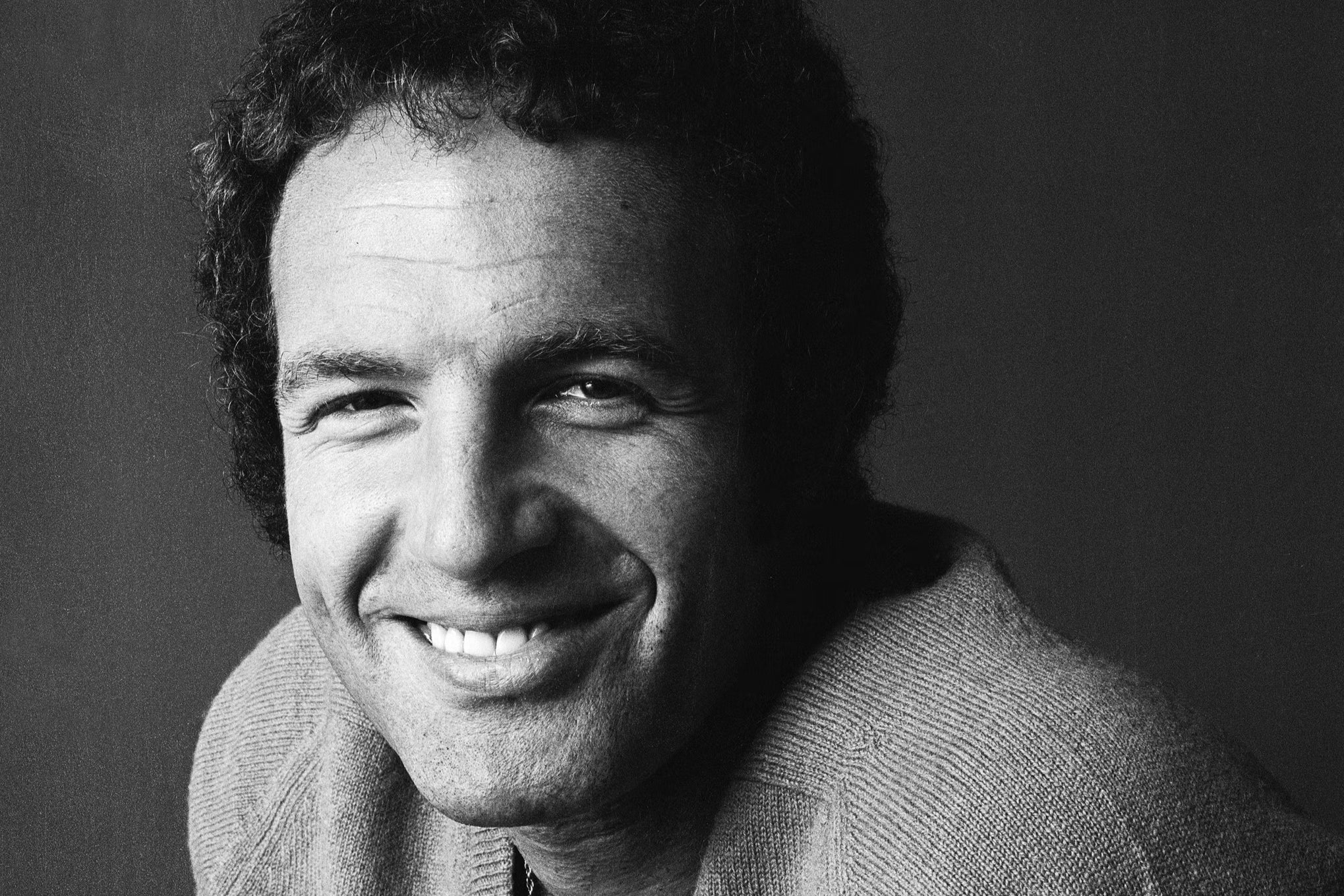

James Caan: ‘I was always cast as Mister Tough Guy – they wouldn’t let me do much else’

The legendary star of The Godfather and Misery was always more than fiery dust-ups and off-screen scandal. He talks to Adam White about typecasting, missing out on an Oscar, and surviving Lars von Trier

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.James Caan is showing off his war wounds. “I’ve got 14 screws in my left shoulder, six in my right, and three in my elbow,” he boasts. “One in my wrist, two in the other wrist, and one in each ankle.” They form a mosaic of brushes with mortality. There was the motorcycle crash, the extensive back surgery, and the time he nearly tore off his thumb in a rodeo accident. That was in 1975, and he had to fly to London a few days later for the royal premiere of Funny Lady. His co-star Barbra Streisand greeted the Queen in a pink Bob Mackie cape. Caan was in line with his right hand wrapped in bandages and his thumb permanently sticking up in the air, like the foam fingers at American football games. He laughs about the state of his bones. “They’ve rejected me at the f***in’ glue factory already!”

Caan may be 80 and held together by nuts and bolts, but it’s nothing to worry about – there’s always been something indestructible about him. Sure, his hothead caporegime Sonny Corleone didn’t make it to The Godfather, Part II, but the rest of his CV is practically a survival guide for all of life’s potential dangers: he’s been pitted against gangsters and corrupt cops in Michael Mann’s Thief (1981); state-sponsored murder in Rollerball (1975); and a hammer-wielding superfan in Misery (1990).

Decades of off-camera excess – the drugs, the multiple marriages, the year he spent living in the Playboy Mansion after a bad divorce – only added to the mythology. Not unlike Sonny, he’s the archetypal dangerous dreamboat with a heart of gold. It was sometimes a burden. “I was always cast as Mister Tough Guy or Mister Hero,” he says. “They wouldn’t let me do much else.”

Caan is in Los Angeles, and not promoting anything. The pandemic has resulted in an absence of acting work, so he’s been making up for it in any way he can – there have been podcast appearances, Caan-branded baseball caps, and a cult Twitter account. He’s wonderful company: cheeky and animated, and keenly aware that his stories are gossipy and star-studded (“You’re gonna love this one!”). Eerily convincing impressions come thick and fast. As do the playful anecdotes.

Rob Reiner casting him in Misery? “It was a private joke – ‘Let’s get the most neurotic actor in Hollywood and put him in a bed for 15 weeks.’” His Eraser co-star Arnold Schwarzenegger? “Our first scene, he goes, ‘Get in the am-boo-lance’ – I said, ‘What the f**k’s an am-boo-lance? Speak English, ya bastard, they’re paying you a fortune!’” His good friend Willie Nelson? “I’ve only inadvertently got stoned with him – every time I get off his goddamn tour bus, I’m doing the f***ing tango or some s**t.” His casual name-dropping is a testament to his long and varied career, and his importance to more than five decades of cinema. Why, then, doesn’t he have an Oscar?

“I really do wish I had an Academy Award,” he says. “But listen, here’s what you gotta know. Number one: anybody who gets cancer [in a movie] automatically wins the Academy Award that year. Number two: I sound like I’m bitter, and I am!” He came close with Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, but it’s been said that category fraud may have split the Best Supporting Actor votes between him, Robert Duvall and Al Pacino – Pacino even boycotted the ceremony after claiming he’d been squeezed out of the Best Actor race to boost Marlon Brando’s chances. “Brando gets Best Actor? Now, wait a minute. How is it possible that Al was a supporting actor in The Godfather? It makes no sense. And then to have it make even less sense, the winner of the Best Supporting Actor award that year was [Cabaret’s] Joel Grey!”

He says that his celebrity also proved a distraction to voters. He remembers visiting members of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association and being pestered with questions about his sex life. “A bunch of these guys had trash magazines at their houses, and all they’d want to know was who I was bedding. What was I drinking? Who was I screwing? Anything but the movie!”

Caan’s sincerity speaks to his upbringing. The son of Jewish immigrants from Germany who first settled in the Bronx and then Queens, Caan grew up flogging meat on Manhattan street corners with his father, and taking part in what he dubs “non-Jewish activities” – boxing, bull-riding, trouble-making. The arts saved him. In the late Fifties, having dropped out of high school, he began studying with the legendary acting guru Sanford Meisner at the Neighbourhood Playhouse theatre. He appeared on Broadway and on television, before moving to California in 1961. He felt like a fish out of water – “I couldn’t understand how you had to drive a half-hour for a newspaper” – but quickly found work as cowboys and toughs. Less remembered are the more sensitive roles – the warm melodrama The Rain People (1969), which introduced him to Coppola, or the love story Cinderella Liberty (1973).

For a time, Caan’s career was on fire. The Godfather cemented him in the American psyche as a figure of scorching masculinity and bruised knuckles. It was a mode he replicated in star vehicles like The Gambler (1974) and The Killer Elite (1975). He did attempt to diversify, writing and directing the tender family drama Hide in Plain Sight (1980), but it only received a limited release. Caan calls it one of his “great disappointments. There were no sharks in it, so these two idiots over at MGM didn’t know what to do with it.” Those who actually saw it loved it. “Francis said it was one of his top five pictures at that time. That made me really happy, because you really wind up making movies for 20 guys, you know? You want your friends to like them.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Everything came crashing down soon after. In 1981, Caan’s little sister Barbara died from leukaemia. “Barbara was like my best friend,” he says. “She was the only person I was afraid of in the world. When she died, passion became this whole thing with me. That’s what I loved about my sister: she was just so passionate about whatever she did. I started doing cocaine, which is like a death sentence. That lasted a while.” Determined to get clean, he left Hollywood, dropped out of the spotlight, and began coaching children’s baseball. It was five years before he made another movie, Coppola’s war drama Gardens of Stone (1987). “That was when I came back!” Caan yells. “With hunger and thirst!”

Caan’s Nineties renaissance was partly aided by old friends eager to see him working again. Reiner, and his production company Castle Rock, put him in Misery and Honeymoon in Vegas (1992), Warren Beatty got him a cameo in Dick Tracy (1990), and James L Brooks pushed him to take a supporting role in Bottle Rocket (1996), the debut of a scrappy upstart named Wes Anderson. It was a shock second wind that lasted a while. He was Hugh Grant’s murderous father-in-law in Mickey Blue Eyes (1999), and Will Ferrell’s crabby biological dad in Elf (2003). The unforgettable Dogville (2003) cast him as Nicole Kidman’s shady old man, and put him in the crosshairs of the famously divisive Lars von Trier.

“Oh, he’s a f***ing wacko!” Caan laughs. On arrival in Sweden, he remembers the filmmaker driving him from the airport to an industrial estate in a beaten-up van. “He says, ‘Jimmy, I take you for a ride!’ He wraps me up in this old duvet in his van, and I remember he had all his dirty clothes in there. I guess every two weeks he’d wash his clothes.”

The set was a bleak one, especially for some of the more elderly cast, like Lauren Bacall and Ben Gazzara. “He was riding roughshod over them – I mean, bad.” Von Trier shot the film on a camera mounted to his shoulder, and he’d run back and forth down a long vertical set that had been dressed to look like a Colorado street. Everyone would have to stay in place and in character, just in case Von Trier passed by.

Caan’s big scene took place in the back seat of a Cadillac, where he found himself completely stranded. “I’m sitting in the back of this thing for hours,” he laughs. “Smoking a cigarette in this silly outfit. Nicole finally comes in with Von Trier, we play this long scene, and then they get out and go back up the street. I’m sitting there waiting. I’m in there for literally three or four hours more, and Nicole is exhausted. After a while I say to the [assistant director], ‘Go tell Nicole that if she needs me, I’m still in the damn car.’ The guy runs off and tells her, and she just starts laughing hysterically. Next thing you know, Von Trier is calling me ‘Laughing Boy’.”

Dogville was a challenge, but it marked the kind of creative endeavour Caan is eager to find again. The pandemic may have slowed him down, but he knows he’s got a couple of great performances left in him.

“I want to do some really good character stuff,” he explains. “Henry Fonda always said he wanted to do a good picture before he passed away. He was never satisfied. I mean, I thought he did a couple of great pictures, you know? But now I get what he meant. I really want to work. I taught an acting class for a couple of years here, which was fun and rewarding, but it’s not as much fun as doing it. I just want the opportunity, while I’m still walking, to do something that will have you calling me and saying, ‘Jimmy, that was really good.’”

He sighs.

“If you know any directors, tell ’em I’m ready.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments