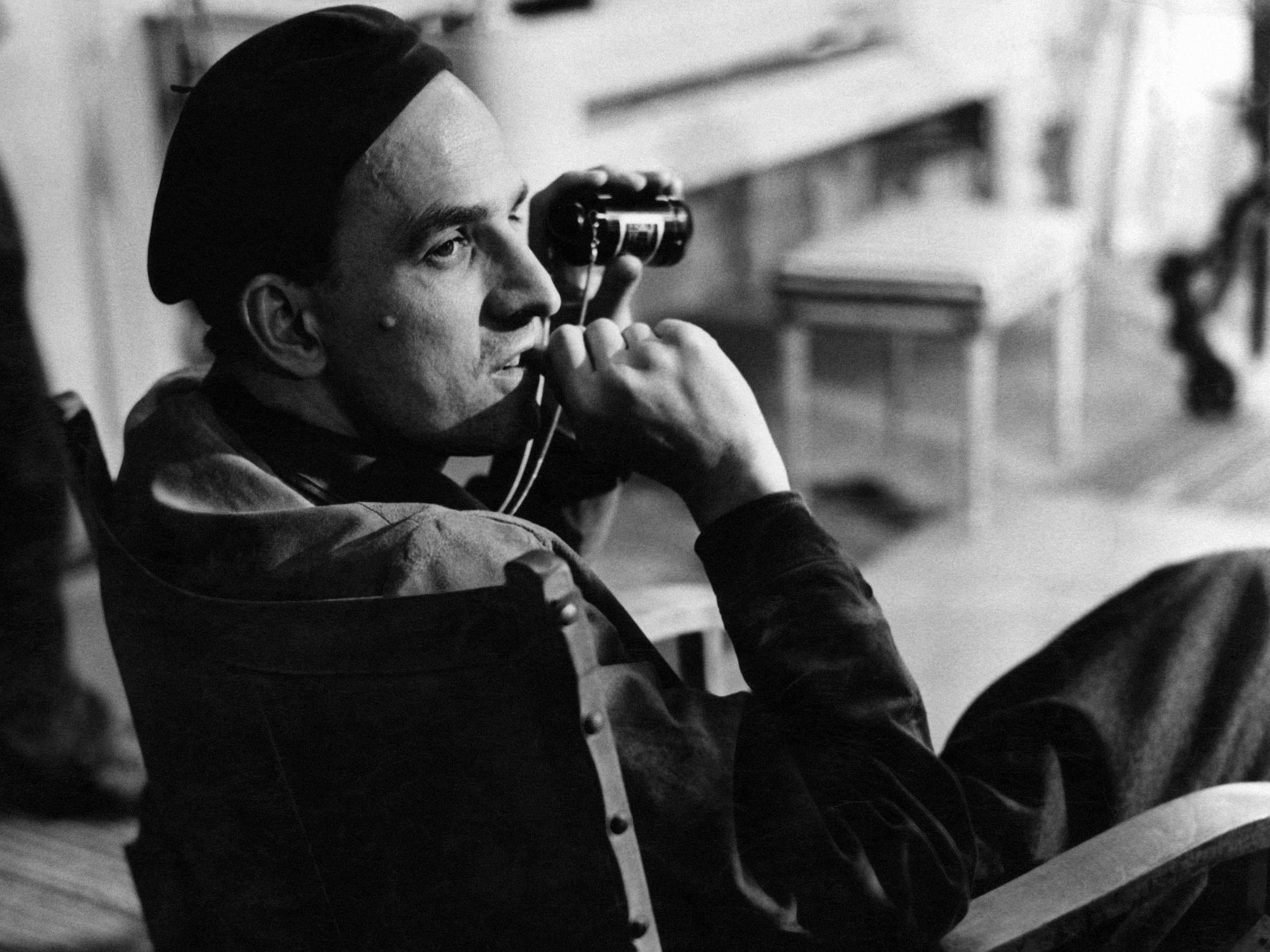

Ingmar Bergman at 100: The master filmmaker who changed cinema remains medium's most misunderstood genius

Revered Swedish director brought new levels of psychological realism to film but his work was too often lazily dismissed as depressing and overloaded with symbolism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ingmar Bergman, the legendary Swedish filmmaker, celebrates his centenary year this month.

Born in Uppsala on 14 July 1918, the son of a Lutheran minister and chaplain to the King of Sweden, Bergman was a shy boy who preferred to play with a magic lantern projector over tin soldiers, building sets and staging plays in his bedroom with wooden marionettes.

Attending Stockholm University in 1937, he became involved in amateur theatrics and began to write and produce his own original scripts with classmates, inspired by Ibsen, Strindberg and Chekhov.

After composing the screenplay for Torment and seeing it filmed by Alf Sjoberg, Bergman directed his own feature Crisis in 1946. So began a career that would see him complete 44 more features, concluding with Saraband in 2003, winning plaudits the world over for such masterpieces as Smiles of a Summer Night, The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, Persona, Cries and Whispers and Fanny and Alexander, an extraordinarily prolific and consistent creative force.

Adored by his disciples, Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen, Wes Anderson, Richard Linklater and Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu among them, Ingmar Bergman’s place at the heart of the world cinema canon is assured and yet he is often regarded as more of a duty than a pleasure, wrongly dismissed as a purveyor of morose and humourless drama about existential despair and crises of faith, overloaded with heavy symbolism.

The stereotype of Nordic gloom is a persistent one, with the likes of Edvard Munch hardly helping matters.

In Bergman’s case, the characterisation of course contains a grain a truth but is desperately lazy and unfair, as even the most cursory introduction will attest.

His films are as full of joy and lust for life as they are with probing psychological fragility and agonising over the meaning of existence in a universe abandoned by an indifferent creator, which admittedly, is enough to get anyone down.

Summer with Monika (1953)

As perfect a vision of young love as you could ask for, Harry (Lars Ekborg) and Monika (Harriet Andersson) quit their jobs and sail out of Stockholm by houseboat to spend a glorious summer together on the islands of the archipelago.

Ingmar Bergman’s place at the heart of the world cinema canon is assured and yet he is often regarded as more of a duty than a pleasure

A million miles from Bergman’s reputation for Scandinavian svarmod (literally ”dark mood”), Summer with Monika was something of a sensation when it first appeared in buttoned-up 1950s Britain, causing a stir and selling extra tickets at the box office on the promise of free-spirited sexual liberation and at least one nude scene. In America, it was sold as “the story of a bad girl”, the trailer explaining that it had been filmed “extra wide for broad screens [and] extra bold for broad minds!”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

All very misleading, the film is actually a touching ode to youth and its protagonists’ dreams of freedom running up against the looming demands of adulthood and responsibility.

The Seventh Seal (1957)

Returning from the Crusades to find the coast in the clutches of the Black Death, melancholy knight Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) encounters the spectre of the Grim Reaper (Bengt Ekerot) on a pebble beach. Losing his soul in a game of chess, Block’s plea to be allowed to carry out one final meaningful act on earth is granted.

Encountering a muralist, a troupe of actors, a cuckolded blacksmith, a corrupt theologian and a mob of religious fanatics on his travels, Block remains tormented by the silence of God.

One of the most famous works in all of cinema, The Seventh Seal is exquisitely shot by Gunnar Fischer in checkerboard black-and-white and contains several of the 20th century’s most unforgettable images, not least the silhouettes of the revellers holding hands for the danse macabre on a barren hillside.

It’s actually a much warmer film than it is commonly characterised as, despite its mood reflecting the director’s anxieties about living in the age of mutually-assured destruction, Bibi Andersson and Nils Poppe inject some much-needed levity as jesters while Gunnar Bjornstrand as Block’s earthy squire Plog is a source of droll gallows humour.

Many will of course have been introduced to The Seventh Seal by the superb parody in Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey (1991) in which the Wild Stallions beat Death at a series of more contemporary games, including Battleships, Cluedo and Twister.

Wild Strawberries (1957)

An unlikely forerunner to the American road movie, Bergman’s Wild Strawberries is a deftly observed character study of elderly professor Isak Borg (Victor Sjostrom), driving south from Stockholm to Lund where he is to receive an award, his memories, regrets and reflections on life inspired by the young hitchhikers he collects en route.

Sjostrom, 78, had been a leading director himself during the silent era and Bergman directly references his superb The Phantom Carriage (1921) in Borg’s nightmarish premonition of his own mortality.

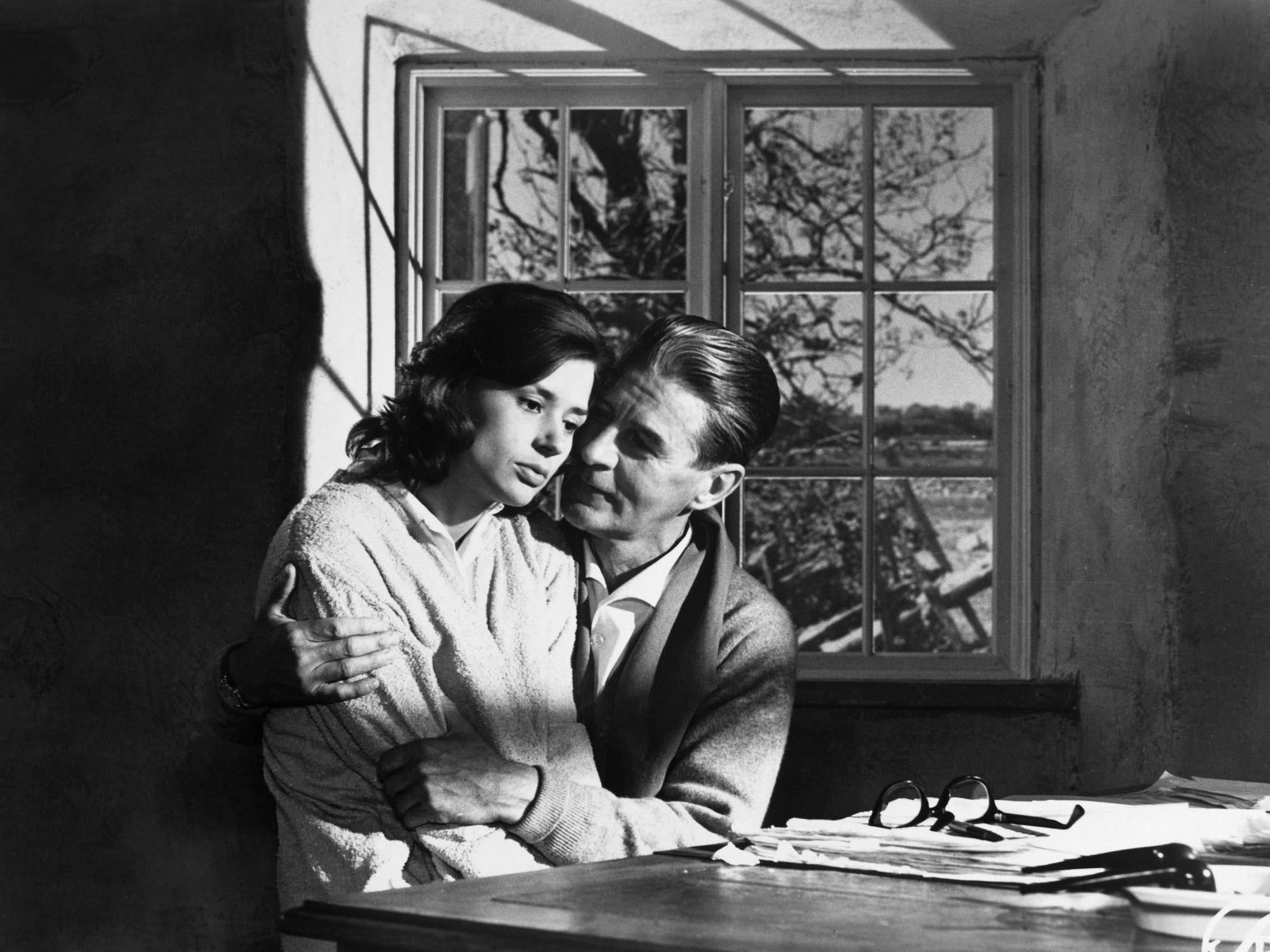

Through a Glass Darkly (1961)

Much truer to the Bergman stereotype, also the subject of ripe parody at the hands of French and Saunders, Through a Glass Darkly is more disturbing than many conventional horror films in its bleakly plausible portrait of a nervous breakdown and marriage of naturalism and expressionism.

Another showcase for Harriet Andersson – with whom Bergman was briefly romantically involved – the actress here plays Karin, a schizophrenic recuperating with her family on a remote island, troubled by her emotionally distant father, incestuous attraction to her brother and conviction that the voice she hears behind the walls of the attic might be God, taking the form of a spider.

The film – part of a loose trilogy exploring faith followed by Winter Light and The Silence in 1963 – was shot in Faro, where Bergman himself lived and where several other of his films took place, including Hour of the Wolf (1968) and Scenes from a Marriage (1972). He died there on 30 July 2007.

Persona (1966)

Persona was likewise shot under the iron skies of Faro and stands among Bergman’s very finest achievements.

His films are as full of joy and lust for life as they are with probing psychological fragility and agonising over the meaning of existence

The film stars the redoubtable Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann as a young nurse charged with caring for a stage actress who has suddenly lost the power of speech. The duo rent a seaside cottage together in the hope of soothing the patient’s condition but their personalities and identities appear to blur, merge and even swap as they are drawn together in near total isolation from society.

As in Through a Glass Darkly, Bergman again places female psychology and sexuality under the microscope, providing his actresses with an extraordinary opportunity they seize, utterly fearlessly, with both hands.

A genuinely mysterious work in the best sense, Persona has inspired both genre and art house filmmakers ever since, from Single White Female (1992) and Mulholland Drive (2001) to Alex Ross Perry’s recent Queen of Earth (2015).

The Touch (1971)

Restored this year by the British Film Institute, this rare foray outside of Bergman’s usual repertory company saw Elliot Gould imported to head the cast.

The star of Robert Altman’s MASH (1970) plays an American archaeologist who arrives in Sweden to examine a statue of the Virgin Mary recovered from an ancient church, befriending a local couple before beginning a torrid affair with the wife, Karin Vergerus (Bibi Andersson).

The film was received with a collective shrug of indifference by complacent contemporary critics but deserves a reappraisal and a much higher profile.

The Touch is a supremely effective portrait of destructive masculinity, Gould’s David Kovac a difficult man haunted by the fate of his relatives in the camps of Nazi Germany and unable to resist his worst instincts to lash out at those who love him.

Autumn Sonata (1978)

Bergman worked with his Hollywood namesake Ingrid only once but the result was stunning.

The actress – immortalised in Casablanca (1942) and Notorious (1946) before being driven out of Los Angeles by the hypocrisy of a moralising press over her affair with Italian director Roberto Rossellini – returned to her homeland for her career swansong, starring as Charlotte, an internationally-renowned concert pianist who dominates her timid daughter Eva (Ullmann).

The star is electric as the damaged diva, wilfully cruel to the child she has neglected in her obsessive pursuit of perfection, not least when Eva herself attempts to play the Chopin prelude she has been working on.

Ullmann though is equally impressive, desperate to please an unpleasable parent and offering a study in shattered confidence that keeps this majestic psychodrama in perfect balance.

Fanny and Alexander (1982)

Ingmar Bergman drew on his own memories for this ambitious period drama, seen through the eyes of the titular children, about a wealthy Uppsala family thrown into turmoil following the death of its patriarch and the mother’s decision to marry the local bishop (Jan Malmsjo), a villain of Dickensian cruelty.

Originally intended to be Bergman’s final project and a five-hour TV series, the film is most commonly viewed in a three-hour theatrical cut.

Very moving and utterly charming, the Ekdahl family Christmas party is one of the loveliest sequences in all of cinema, a feast of candlelight, dancing and pillow fights perfected by the shock of Fanny and Alexander’s roguish uncle setting alight to his own after-dinner farts for their amusement.

Good triumphs over evil at the close – and there’s nothing more upbeat than that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments