On Chesil Beach is the latest Ian McEwan novel adapted for the big screen. What makes them so irresistible for filmmakers?

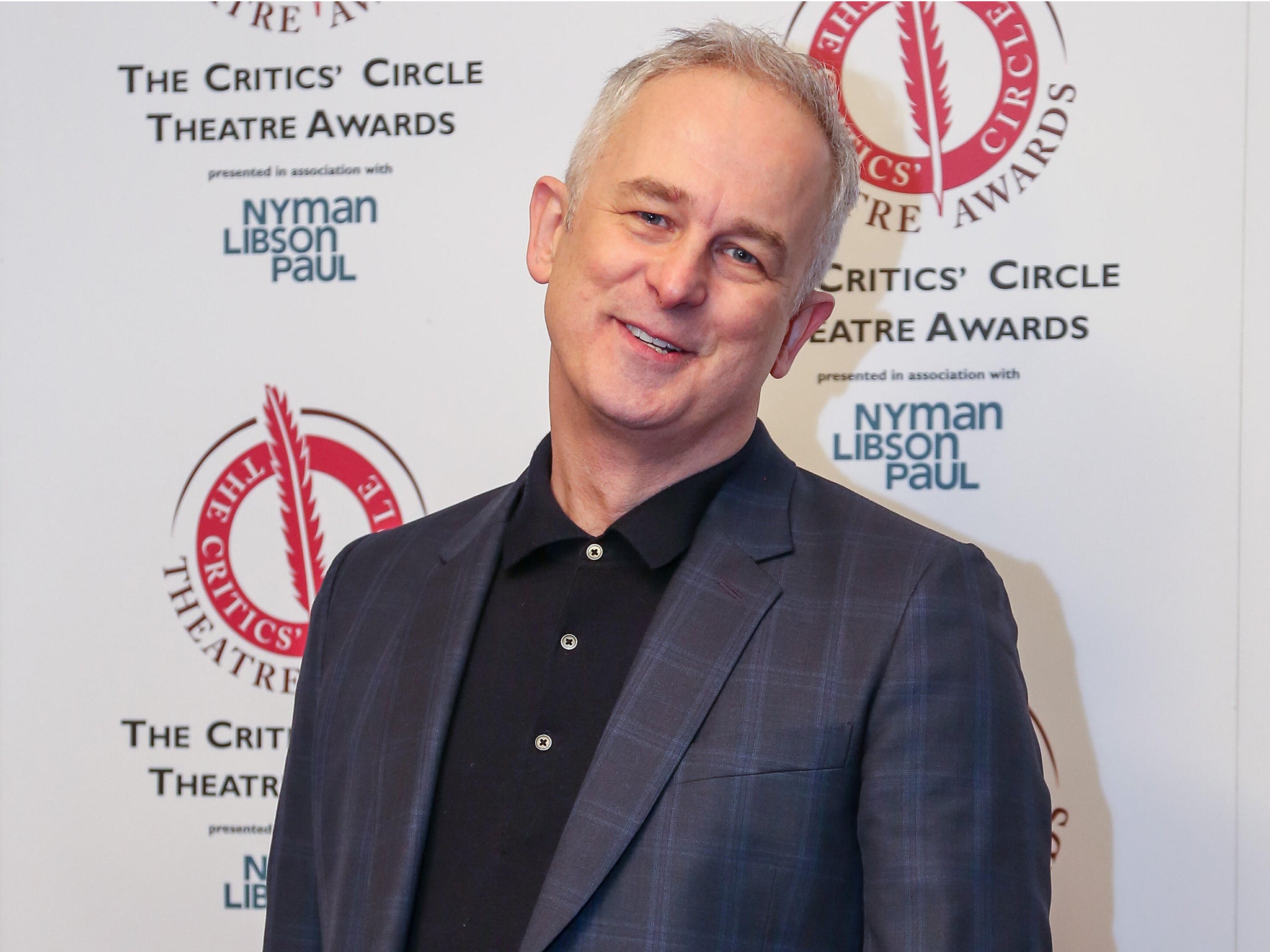

The novella about a couple on their wedding night is the latest of the British author's works to be filmed. Ian McEwan, director Dominic Cooke and star Billy Howle discuss the process

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.From Roger Michell’s 2004 interpretation of 1997 novel Enduring Love to Joe Wright’s 2007 Oscar-winning adaptation of 2001’s Atonement (featuring “that green dress”), Ian McEwan’s vivid depictions of passion and intimacy, trauma and tragedy, and the complexity of human relationships have long been capturing the imaginations of both readers and cinema-goers alike.

And the author is enjoying something of a renaissance as a storyteller on the screen. This week sees the release of On Chesil Beach, a film based on his perfectly-crafted 2007 novella set in Dorset in the summer of 1962. It pivots around the wedding night of two young innocents, Edward and Florence, played exquisitely by Billy Howle and Saoirse Ronan. McEwan wrote the screenplay himself – not something he has often done.

It comes in the wake of a 2017 BBC film adaptation of three-decades-old The Child in Time (1987) starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Kelly Macdonald, and ahead of Richard Eyre’s film version of The Children Act, based on McEwan’s 2014 book and starring Emma Thompson, slated for later this year.

So what is it about this author’s writing that has not only made him one of our best-loved contemporary British writers but continually attracts filmmakers to his stories?

Acclaimed theatre director Dominic Cooke, making his feature film debut, explained that for him: “It was the detail of it, the honesty of it. It’s uncompromising, it’s unsentimental. But it’s also compassionate to the characters.

“These two products of the uptight early Sixties, struggling so hard to become adults and become themselves, really moved me.”

Cooke believes it is McEwan’s particular skill as a precise and visual writer that makes his work irresistible for adaptation: “Everything is fully visually imagined, the sense of place is always crucially important.”

Furthermore, the three-dimensional nature of the characters McEwan is incredibly appealing for actors: “They can see in his novels really interesting and complicated, contradictory, rich characters – those things are an intoxicating mix.”

Evidence of this is clear in the back catalogue of films based on his books, which forms a read off of 21st century film talent: Rupert Everett, Christopher Walken, and Helen Mirren in Paul Schrader’s Venice-set drama The Comfort of Strangers (1990); Anthony Hopkins in John Schlesinger’s dark The Innocent (1993) set in 1950s Berlin; Charlotte Gainsbourg in Andrew Birkin’s The Cement Garden (1993) based on his very first, macabre novel, and Ewan McGregor in Denis Lawson’s Solid Geometry (2002), adapted from a short story in First Love, Last Rites.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Enduring Love (2004) launched Daniel Craig onto a career path that led to James Bond notoriety, while Atonement confirmed Keira Knightley’s place as the English Rose of cinema and James McAvoy as a prime UK export. Not forgetting the panoply of household names who crop up in supporting roles in those movies from Bill Nighy to Benedict Cumberbatch.

On Chesil Beach is no exception. Lead American-Irish actress Saoirse Ronan herself had her big break in an Oscar-nominated performance as young Briony Tallis in Atonement at just 12. A decade on, Ronan is riding a wave of heightened critical-acclaim from her role in Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird.

As we’ve come to expect from her, Ronan’s take on Florence captures layers of emotion, in a performance she says was made easy by the “brilliant and relatable” writing.

“The camera loves her,” adds Cooke. “She offers something up every moment. She has a wisdom way beyond her years. She’s really special.”

Starring opposite her as Edward, Billy Howle hasn’t yet built the same recognition, though he starred in the film version of The Sense of an Ending, adapted from the novel by McEwan’s contemporary Julian Barnes, and is in the forthcoming The Seagull, again opposite Ronan.

Cooke sees him as a real find: “We were looking for something of Albert Finney in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, [or] Alan Bates. Those guys from the early Sixties who had a kind of ruggedness but also a vulnerability. It took us a long time to find that person but when we found Billy it was absolutely clear he was the one.”

And he’s a perfect pairing with Ronan, with whom he shares a palpable on-screen electricity. Both sets of parents – Anne-Marie Duff and Adrian Scarborough, and Samuel West and Emily Watson – complete the exceptional casting, aided by Cooke’s background in theatre: “It was all about who was right.”

That’s not to say adapting McEwan’s work, often laden with idiosyncratic literary styles, multiple time jumps and conflicting narrative perspectives, is without its challenges

“Thematically, his work is multifaceted,” points out Howle in our interview. “It can feel very dense on first reading.” In the case of On Chesil Beach, he adds: “It is a really difficult read, as a heartbreaking, irresolute love story.”

Speaking at the film’s preview, McEwan admitted the decision to write the screenplay was motivated by one simple fact: “I didn’t want anyone else to do it. It’s a very intimate and, I hope, tender story and I could see a trillion ways to make the world’s worst movie: you could make it semi-pornographic, you could make it satirical, or rather derisory, or all very sentimental.”

Instead, McEwan was able to play a key role in shaping the film: “The fact that it’s a short novel appealed to me because screenplays and novellas have a lot in common. But in the process of doing it I found all kinds of appealing technical problems, such as there’s very little dialogue in the first half – so I had to invent these characters all over again.”

A key draw for Cooke is an unmistakable Englishness that McEwan deals with in each of his novels. And in On Chesil Beach, it’s one which moves away from the rose-tinted image of better days gone by to something more critical.

“In some ways the film breaks the contract of many British period movies in that it’s relentlessly anti-nostalgic. It’s saying, ‘let’s not go back’. These kids are carrying with them into that hotel room these terrible, almost toxic inheritances from their individual family pathologies, but also from the societies they’re living in.”

For the director, this was something he identified from his grandparent’s generation: “There is a lot about the stifling emotional inarticulacy of the characters I recognise. They had a reserve, and almost an intolerance of emotion. Edward and Florence’s parents had lived through both world wars and that leaves it scars.”

And it’s an inheritance Cooke believes has shown itself as even more pertinent now, the film becoming rather timely by dealing with Britishness “at a point where this country really is having an identity crisis”.

A further traceable element through all McEwan’s work is a troubled, troubling undercurrent. As Cooke reflects: “There is a darkness to his writing. But it’s not relentlessly nihilistic or pessimistic. There’s a vulnerability to the characters which makes them redemptive even if the situations are cruel often and harsh.”

In particular, when viewed in parallel with Enduring Love and Atonement, there emerges a preoccupation with how a life can turn on a single moment, decision or incident.

“I am interested in chance in people’s lives,” McEwan recognises. “We’re all the children of parents who could have easily not met: your mother might have stayed in to wash her hair, might not have met your father. So chances are very big factor in all my novels, though in very different forms. Sometimes we only recognise turning points in our lives many years later, in retrospect.”

With McEwan, you are not often in for neat resolutions and happy endings. But in tackling the thorny nuances of human interaction, his stories find forensic ways to uncover certain truths.

“He’s interested in exploring the edges of experience and the difficult stuff, he doesn’t turn his gaze away from that,” says Cooke. “If he was a colder writer I wouldn’t like his work as much as I do. But it’s balanced out by a sense of being on the side of the characters.”

A sense he remains true to in his take on On Chesil Beach, where we root for Florence and Edward, as we did for Joe and Claire, Cecilia and Robbie, right till the last, however futile it may be.

On Chesil Beach is in UK cinemas from 18 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments