A year after #MeToo, Hollywood has a headache money can’t cure

‘There is fear. There is tension. And there is no end in sight.’ In a century of film, rarely if ever has so much upheaval arrived so fast and on so many fronts, says Brooks Barnes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Resting in the film executive’s sweaty palm was an extremely long rectangular pill stamped “X-A-N-A-X.”

“Want half?” he says.

It was a hot, windy night in mid-September, and we were walking to our cars after meeting for drinks at the Polo Lounge in Beverly Hills. I had expected a lively, gossip-fuelled conversation, nothing for attribution, of course. Instead, our talk was more like a gloomy therapy session – in which I was the shrink.

Over a vodka martini (his) and a Diet Coke (mine), he gripes that the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements had gone too far, too fast. He says he was “depressed” about moviemaking for the first time in his decades-long career, the result of endless remakes and superhero movies. (“Maybe we should remake Dumbo as a live-action picture. Oh, wait. It’s actually happening.”) And how was it possible that one of the all-time-great studios, 20th Century Fox, was being folded into Disney, ending an era of six major studio competitors?

I rebuffed the Xanax by joking that even half looked big enough to tranquillise the Incredible Hulk and drove home. But the unsettling encounter stayed with me. I knew it wasn’t just one guy having a bad day. Hollywood is in the midst of a full-blown identity crisis.

Based on the box office, studios should be full of people turning cartwheels and sprinkling confetti. After a sizzling summer, theatres are having their busiest autumn on record. October ticket sales were up a fat 45 per cent compared with last year, according to Comscore. Coming soon are anticipated holiday juggernauts like Aquaman and the animated Ralph Breaks the Internet. And the big film factories, after largely ceding the Academy Awards to tiny art films over the past decade, are back in the thick of the Oscar race. Crowdpleasers like Black Panther (Disney) and A Star Is Born (Warner Bros) are serious best picture contenders.

But euphoria is almost nonexistent in studio hallways. The movie capital is instead mired in a profound malaise.

The reason involves fallout from the #MeToo earthquake, both the positive changes it forced, and, lately, the pushback it has incurred. Contributing are the megamergers that have left Warner Bros and 20th Century Fox with new owners and may find Sony Pictures, Lionsgate and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer sold or reconfigured before long. The steady march of big tech into entertainment also plays a role. Hollywood power players have long clung to the fantasy that the world revolves around them, as if it were 1940 and they were all Louis B Mayer. But that delusion has been hard to sustain with Amazon and Apple throwing around billions to make TV series, some featuring megawatt stars like Julia Roberts and Jennifer Aniston.

There is fear, but there is also anger. Women with a point of view, many men with another. Older executives not understanding why younger executives and employees are so adamant about diversity and inclusion. Younger executives and employees angry at their bosses for letting it get this bad

In the 100-year history of Hollywood, rarely if ever has so much upheaval arrived so fast and on so many fronts. For streaming upstarts like Netflix and Amazon Studios, where the cultures are still forming and money is gushing, the disruption is invigorating. But the rest of the entertainment business is filled with a deep unease. It is not just old-guard men moping about the end of their supremacy. It’s mid-level vice presidents at merging companies worried about whether they are about to lose their jobs. It is people initially excited by the Time’s Up insurgency who are concerned about stagnation or even backsliding.

“The vast majority of people feel completely unmoored,” says Amy Baer, whose 30-year movie career has taken her from Sony Pictures to CBS Films to independent producing. “There is fear. There is tension. And there is no end in sight.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

‘Yap, yap – go back to your kennels’

It has been a little more than a year since Hollywood was rocked by accusations of sexual harassment and worse against producer Harvey Weinstein. The #MeToo and Time’s Up reckonings have resulted in the ouster of producers (Weinstein), actors (Kevin Spacey), studio bigwigs (John Lasseter), directors (Brett Ratner) and chief executives (Leslie Moonves). In September, when The Hollywood Reporter published its annual list of the 100 most influential people in movies and TV – a group that usually looks remarkably similar year after year – there were 35 new names, 40 per cent of them women or people of colour.

Publicly, everyone in Hollywood says the same thing, almost as if reading from talking points written by publicists: we applaud this long overdue progress and will do everything in our power to make sure the culture changes.

What some people in senior jobs say privately is a different story. In hushed lunches at the Palm and over cocktails at Tower Bar, established men – producers, directors, executives – share resentment about aggressive efforts by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to diversify its membership, which is overwhelmingly white and male. A glimpse of this animosity came in April, when Bill Mechanic, an Oscar-nominated producer and former Fox executive, resigned from the academy’s board. “We have settled on numeric answers to the problem of inclusion,” Mechanic wrote in his resignation letter, which was leaked to the news media. “One governor even went as far as suggesting we don’t admit a single white male to the academy, regardless of merit!”

Some men in Hollywood quickly revert to sexist and offensive language when speaking anonymously, which is the only way the most powerful ones will talk to reporters. (This is a place, after all, where even corporate publicists say things like, “Strictly off the record, I have nothing to say.”)

“Yap, yap – go back to your kennels,” a leading film producer told me over lunch recently at a Burbank sushi spot. He was talking about Time’s Up, the organisation founded in January by Reese Witherspoon, Shonda Rhimes and other powerful Hollywood women to fight workplace sexual harassment across the country. Realising he had misread his audience, perhaps because of the startled look on my face, he started to backtrack.

Baer, who was elected president of Women in Film, a deeply rooted advocacy organisation, over the summer, says one male film executive she has known for decades “seized up” over lunch when she casually asked how many women he employed.

“I was just curious,” Baer says. “This guy is one of the good guys. But he looked at me like ‘Oh, no – here she comes,’ like I was taking aim at him, and that speaks to the tension.”

Beth Gulas, a management and organisational consultant who focuses on the entertainment industry, says Hollywood was more out of alignment than it seemed on the surface. “There is fear, but there is also anger,” Gulas says. “Women with a point of view, many men with another. Older executives not understanding why younger executives and employees are so adamant about diversity and inclusion. Younger executives and employees angry at their bosses for letting it get this bad.”

The only unifying characteristic: “All of this change is having a massive impact on people,” she says. “Massive – as in bigger than people really want to say out loud.”

Gulas, whose past clients include Comcast and Legendary Entertainment, noted that Hollywood was dealing with upheaval on multiple fronts. The #MeToo movement happened to arrive at the same time as sweeping consolidation, driven by business realities beyond the box office, including the sputtering of what has long been the entertainment industry’s engine: cable TV. Within the past year, AT&T completed its $85.4bn (£66bn) takeover of Warner Bros, HBO and the Turner cable channels, which include TNT, CNN and Cartoon Network.

And the Walt Disney company knocked Hollywood on its heels by swallowing the historic 20th Century Fox movie and TV studio; the FX and National Geographic cable channels; and a controlling stake in Hulu, among other entertainment businesses long owned by Rupert Murdoch.

AT&T told its new Hollywood employees in July to brace for “a tough year” of change ahead. A housecleaning began last month.

Hundreds if not thousands of Fox employees may lose their jobs under the Disney merger. Disney managers, meanwhile, are bracing for the difficult job of smoothly integrating the Fox people who will remain – the “feral foxes,” as one Disney-associated producer put it. The Disney culture is almost militaristic in its respect for hierarchy and focus on its family-friendly mission. Fox is known for openly warring executives, particularly in its film division, and embrace of coarse movies (Deadpool) and series (American Horror Story).

‘Disgrace insurance’ is real

Prompted by #MeToo and earlier controversies like the #OscarsSoWhite outcry, there has been a stark shift towards greater diversity in casting, crew staffing and storytelling. There are new rules for auditions (no more hotel rooms) and zero-tolerance responses to offensive jokes on Twitter, as director James Gunn discovered in July when Disney fired him from the Guardians of the Galaxy series. New human resources chiefs have been hired or will soon be at CBS, Sony Pictures, Viacom, Pixar and Endeavor, which owns Hollywood’s largest talent agency, WME.

“It used to be more difficult to secure protections for actresses who are not household names – for actresses with the least power,” says Jamie Feldman, an entertainment lawyer whose clients range from A-listers (Viola Davis) to rising stars (Juno Temple). “If you pushed back on nudity, for example, there was often this cavalier tone about her needing to understand the price of entry. That has changed completely. People are very conscious about not wanting to be seen as disrespectful.”

Companies are looking for protection, too. Multiple studios are working to include morality clauses in their talent contracts. Some unions prohibit such provisos, but where possible, Fox is considering language stipulating that it can fire anyone whose conduct “results in adverse publicity or notoriety or risks bringing the talent into public disrepute, contempt, scandal or ridicule.” Spotted, a startup that evaluates celebrity endorsement-deal risk, has lately been talking about “disgrace insurance,” which is offered by multiple underwriters and was also the subject of a panel at the most-recent Producers Guild of America conference.

“Brands have become more leery of aligning themselves with actors because of #MeToo,” says Janet Comenos, Spotted’s chief executive. “That means potentially millions of dollars not flowing into the Hollywood ecosystem – the managers, the agents.”

It is impossible to know, of course, whether such changes will end or even dramatically reduce the abuses of power that have made Hollywood the centre of the #MeToo revolution. There is clearly a palpable difference in behaviour. But will an out-of-control business culture that operated for decades be permanently transformed? It will take years to find out, and there is a growing disillusionment among some of those on the front lines.

“Generally speaking, I still don’t see a real willingness to do what it takes to change a troubled culture,” Gulas says. “It takes investment, and it takes a lot of stamina to see it through. Most of these companies want a quick solution. They want a Band-Aid.”

In some areas, there are signs of regression. The number of women running film studios is actually going in reverse; Stacey Snider, chief executive of 20th Century Fox, will find herself displaced when Disney completes its takeover of Fox in the months ahead. At least nine additional female senior executives have left their jobs over the past year, including Cyma Zarghami, president of Nickelodeon Group, and Diane Nelson, president of DC Entertainment.

Ten months after actresses, clad in black, brought women’s rights activists as their guests to the Golden Globes, red carpets have returned to selling sex appeal and “Who are you wearing?” is again the default question. Studios and television networks have been reluctant to publicly commit to greater diversity and inclusion in casting and hiring crew members. Only Warner Bros, the lone studio run by a person of colour (Kevin Tsujihara), has done so, stipulating that it would hold itself accountable by issuing an annual report on its progress.

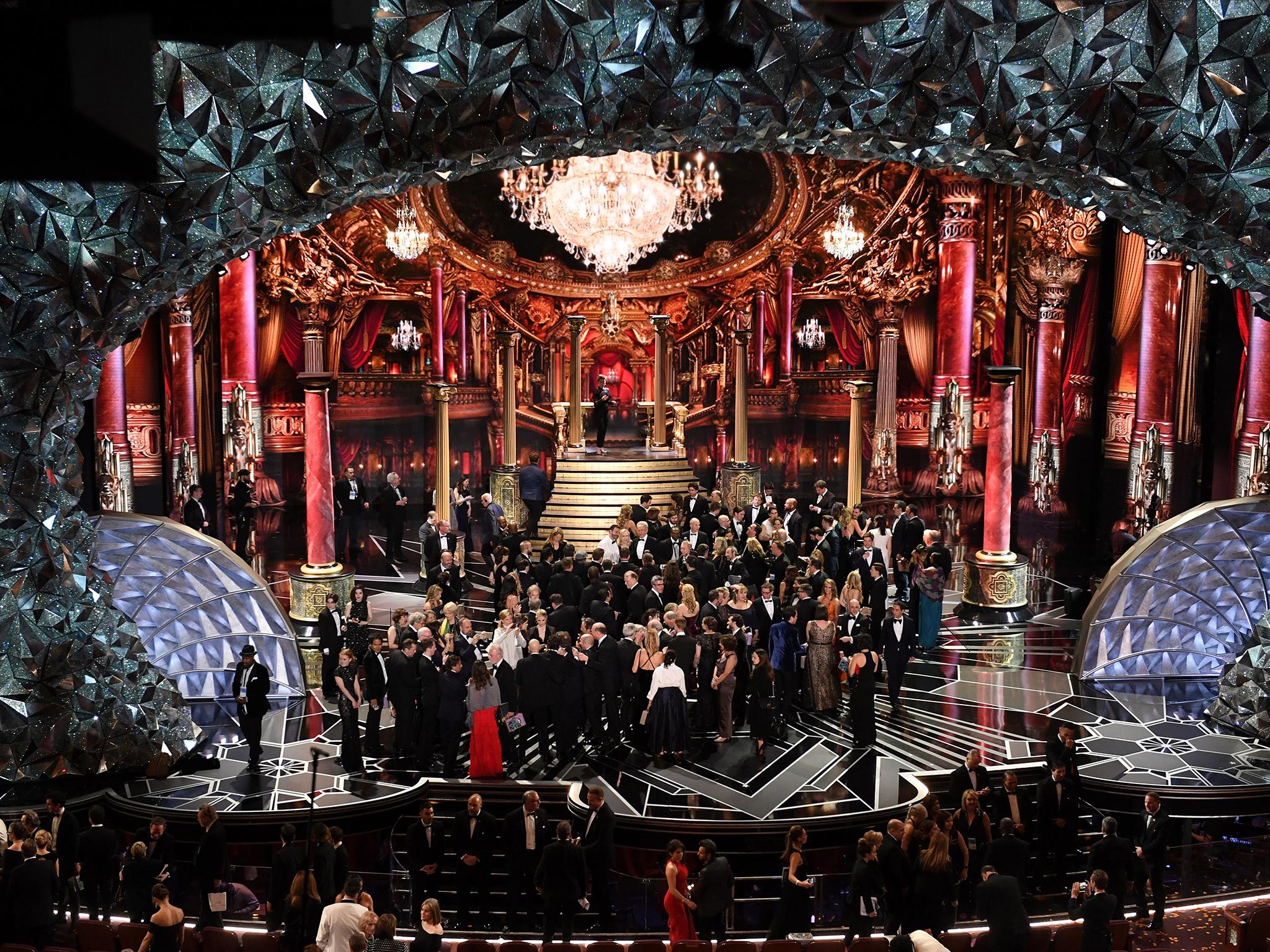

And despite the cheers that greeted Frances McDormand’s best actress acceptance speech at the last Academy Awards, in which she put the contractual term “inclusion rider” into the public consciousness, few stars have been willing to publicly demand them. Inclusion riders are stipulations that might require a cast and crew to, for example, be 50 per cent female, 40 per cent underrepresented ethnic groups, 20 per cent people with disabilities and 5 per cent LGBT+ people. In failure, studios would be forced to pay fines, to be put into a diversity-minded scholarship fund for student filmmakers.

Generally speaking, I still don’t see a real willingness to do what it takes to change a troubled culture. It takes investment, and it takes a lot of stamina to see it through. Most of these companies want a quick solution. They want a Band-Aid

The six major studios (soon to be five) declined to comment on inclusion riders. One studio chief, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he feared drawing the fury of advocacy groups, says lawyers at his company nixed the notion because they feared that such quotas might prompt lawsuits under federal and state anti-discrimination statutes.

Now streaming on Netflix

On a more meta level, Hollywood is also wrestling with a question that challenges its core identity: What is a film? No movie backed by Netflix – shown primarily on TV sets – has ever been nominated for best picture at the Academy Awards, but that could change this year with Roma, a black-and-white period drama directed by Alfonso Cuarón that has been hailed as a masterpiece by critics who have seen it at festivals. It arrived in a smattering of theatres this week and will be show on Netflix on 14 December.

Netflix and other tech companies, including Apple and Amazon, have been steadily poaching talent from established companies by offering eye-popping pay packages, leading to more anxiety. You can even feel it at Disney, which is the strongest of the old-line entertainment companies. Over the past 15 months, Disney has lost some of its marquee talents to Netflix, including producers (Rhimes, Kenya Barris) and executives (Tendo Nagenda, Jamila Hunter). That kind of brain drain is not good for morale.

But studios are mostly worn down from #MeToo fallout. They have become accustomed, for instance, to rolling public relations emergencies.

In August, Universal Pictures scrambled to contain a crisis that arose from the set of Good Boys, an upcoming comedy, when a photo of a young actor in what appeared to be blackface makeup was leaked to TMs; the makeup had been applied to a lighter-skinned African-American actor, who was standing in for a darker-skinned black actor in a lighting test. In September, 20th Century Fox says it had deleted a scene in The Predator after learning that an actor with a bit part was a registered sex offender. The director of the film, Shane Black, initially defended the casting and then reversed himself, leading to an ongoing news story.

As Baer says, there is no end in sight. In recent weeks, Fox had to bob and weave through its marketing campaign for Bohemian Rhapsody, which carried Bryan Singer’s name as the credited director. Singer, whom Fox fired near the end of production for questionable on-set behaviour, has long been trailed by sexual misconduct allegations. He has repeatedly denied any such behaviour, issuing another statement of innocence on 15 October in anticipation of a still-unpublished exposé in Esquire.

Some movies have been stranded completely, imperiling more than $150m in production costs. They include Woody Allen’s A Rainy Day in New York, which Amazon has refused to schedule for release (Allen’s team insists the film will find distribution in 2019) and Morgan Spurlock’s documentary Super Size Me 2: Holy Chicken!, which was dropped by distributors after Spurlock acknowledged sexual misconduct.

There were a half dozen films left unreleased by The Weinstein Company, which imploded last spring. Some of those, including The Upside, starring Kevin Hart, Bryan Cranston and Nicole Kidman, will start to make their way to theatres in January through new distributors – undoubtedly amid publicity-trail questions of the stars about Weinstein, who has lately been battling sex-crime charges in court.

“Established protocols – decades worth – are changing at lightning speed,” Baer says. “For people like me, who believe change is desperately needed in Hollywood, that is exciting. But a lot of people are lost in anxiety.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments